More than 6 million birds have been vaccinated against avian metapneumovirus (aMPV) type B since the September rollout of the first experimental autogenous vaccine produced in the US, according to Ivan Alvarado, PhD, associate director, scientific marketing affairs, Merck Animal Health.

In August, USDA’s Center of Veterinary Biologics (CVB) approved the manufacturing and sale of the vaccine, which is used for broiler breeders, commercial layers and turkey breeders.

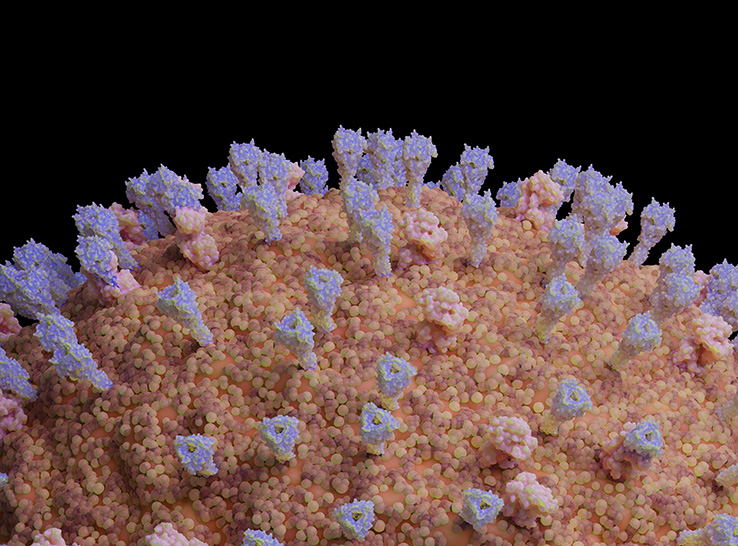

The vaccine protects poultry against aMPV, a deadly virus that causes severe respiratory distress, leading to increased mortality and reduced egg production.

“An autogenous biologic goes through the same batch-safety and purity testing as a commercial vaccine,” Alvarado added.

Team effort

The widely used autogenous vaccine is available through an agreement between Merck Animal Health and Cambridge Technologies, an independent custom-vaccine company based in Worthington, Minnesota.

Cambridge developed the vaccine and manufactures it at its USDA-licensed, 37,000-square-foot manufacturing facility, which features state-of-the-art fermentation suites. The company also holds the CVB license for the experimental autogenous vaccine.

Merck Animal Health, which has an extensive portfolio of poultry vaccines, is the exclusive sales agent for the vaccine and handles technical support in the field.

“This is our first viral autogenous vaccine for poultry,” reports Ben Hause, PhD, chief scientific officer, Cambridge Technologies, which along with its legacy companies has produced autogenous vaccines for the swine and cattle industries for more than 40 years.

“We obtained samples from flocks in the field that had tested positive in university labs to aMPV subtype B. We were able to isolate that virus on our continuous cells for production and were able to grow aMPV type B to high titers.”

Adjuvant essential

For safety reasons, regulators require bacteria and viruses used in autogenous vaccines to be inactivated.

“One problem with inactivated, or killed, vaccines is they do not induce as strong of an immune response as a live virus,” Hause says. “To make the killed vaccines work better, we use an adjuvant to help stimulate a robust immune response.”

Cambridge conducted small, in-house trials to determine how best to formulate the aMPV vaccine for poultry. Scientists tested different amounts of oil-and-water adjuvants and followed up with tests looking for reactions on the birds.

“We saw no adverse reactions from adjuvants. It looked real good,” Hause adds.

Cambridge also tested birds for antibodies after vaccination and determined the vaccine produced a robust antibody response. The trial results formed the basis for how Cambridge produces the vaccine today.

Oil-in-water adjuvant benefits

The adjuvant Cambridge uses for the new aMPV vaccine is oil-in-water. With water as the emulsion, vaccinations cause fewer tissue reactions, Alvarado explains. Typically, poultry vaccines use water-in-oil emulsions with oil as an adjuvant.

To see how well the adjuvant worked, two field evaluations were conducted to check tissue reaction post-vaccination. “We are very happy with the results,” Alvarado says. “The reactions are mild — milder than what we’ve seen in commercial vaccines.

“This is good because less stress on the bird means the impact on body weight gain and uniformity is less.”

In addition, the water-based adjuvant makes the vaccine to diffuse more easily into the muscle. Vaccinations are administered by intramuscular, subcutaneous or inguinal fold routes.

CVB oversight of vaccine sales

Normally, this new aMPV vaccine would have been a standard autogenous vaccine, Hause says. But USDA has put special regulations on it, calling it “experimental autogenous”. This status requires pre-approval from Cambridge and the state veterinarian for purchase of the vaccines.

To obtain the aMPV vaccine, Merck’s poultry team works closely with customers to gather the necessary information requested by Cambridge. Customers who want to buy vaccines must provide a complete list of all locations where the vaccine might be used. The lists are sent to Cambridge for pre-approval.

Once pre-approved, customers then let Merck’s poultry team know how many farms and vaccine doses are needed on monthly basis. Merck sends this info to Cambridge for their approval. Final approval must then come from the state veterinarian. After the approvals are completed, Merck delivers the vaccine to specified locations. The total approval process usually takes 2 to 3 weeks.

Future for aMPV vaccines?

Since an experimental autogenous designation is rarely used, the future for these vaccines is unknown. But Cambridge is moving toward full licensing.

“One condition on ‘experimental autogenous’ that was dictated to us from CVB was we must progress towards conditional and then full licensure,” Hause says. “We are required and are moving towards licensure.

“Autogenous was originally designed for emergency situations like this with new AMPV and no vaccines commercially available,” he adds “Working together with Cambridge was essential to provide a rapid solution to the aMPV challenge facing our customers.”

In addition to work on a fully licensed aMPV type B vaccine, Cambridge is also working on an aMPV type A autogenous vaccine.

Alvarado is optimistic about future vaccines to protect against aMPV outbreaks.

“CVB has really been working together with the industry and we have been able to have vaccines in less than a year,” he says. “They are also evaluating a couple of live vaccines, which will be other tools we can use to control aMPV.

“In the meantime, we have plenty of supply,” Alvarado adds. “We have a good reserve because we know with winter approaching, we will need to keep our birds warm which also creates some respiratory challenges. The possibility of the virus coming back this winter is high.”

For more on the registration, testing and manufacturing process of the aMPV vaccine supported by Merck, click here.