By Matthew J. Hardy, MSc

AgriNerds – Co-owner, Waterfowl Biologist and Co-director of Ecological Modeling

Chester County, Pennsylvania

(Part 2 of 4, Waterfowl migration and HPAI risk across North America)

Each year, as millions of waterfowl soar across North America’s skies, they follow ancient migratory routes that span thousands of miles across all four major flyways: Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic.

In Part 1, we explored the world of dabbling ducks — surface feeders that forage in shallow waters — like Mallards and Northern Pintail. In Part 2, we are diving deeper, literally, into the fascinating lives of the diving ducks.

Unlike dabblers, diving ducks can plunge 20 feet (6.1 meters) beneath the surface to search for food, using their powerful legs and compact, heavier bodies to pursue food in deeper lakes, rivers and coastal bays. Their legs are positioned toward the rear of their bodies, an adaptation that gives diving ducks impressive underwater thrust, though it leaves them awkward and unsteady when moving on land. These species include the Bufflehead, Ring-necked Duck and, my personal favorite, the unmistakably striking Canvasback.

For this article, I am making the distinction between diving ducks and sea ducks. There is undoubtedly overlap between the two, but I personally distinguish diving ducks from their saltwater cousins, the sea ducks, which are adapted to life on the ocean (e.g., Eiders, Scoters and Long-tailed Ducks). Although both groups are adept underwater foragers, divers are most often found in freshwater or brackish habitats and include some of the most dynamic and migratory birds in the waterfowl world.

Dabbling ducks often bring ponds and wetlands to mind, but diving ducks exhibit a more diverse use of the landscape. They move through rivers, occupy deep, quiet lakes and abandoned quarries, and gather in estuarine bays, highlighting the complexity of monitoring and managing the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) across the US.

Diving ducks, why they matter

Diving ducks can be found in a variety of habitats and aquatic environments. But, staying true to their name, they prefer deeper waters, such as lakes, rivers and estuarine bays, rather than very shallow wetlands (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Species of diving ducks

Unlike dabbling ducks that feed by tipping forward to forage near or just under the surface, diving ducks search for food by fully submerging, often diving to the bottom of the waterbody (e.g., lake, reservoir, river). Their diet is diverse and includes crustaceans, mollusks (including crabs and clams), aquatic insects and submerged vegetation and tubers. This diet, centered around benthic organisms, links diving ducks to a different ecological niche but also exposes them to pathogens concentrated in sediments and water.

Studies have also found avian influenza virus in clams, mussels and oysters along the Chesapeake Bay and crabs in Asia.1,2 These food items are a favorite food of many diving ducks, potentially highlighting an unexplored interface of transmission.

Diving ducks can gather in large groups on the water, often referred to as “rafts,” where there is safety in numbers. They frequently share habitats with a wide range of other waterfowl and aquatic species, such as dabbling ducks, shorebirds, gulls and even mammals, creating a complex web of interactions.

Because diving ducks often use diverse aquatic environments, from freshwater lakes to estuarine bays, they serve as vital bridges connecting different bird communities and ecosystems. This constant contact makes them key players in the transmission of HPAI.

Varying annual HPAI incidence

Most migratory diving ducks in the US spend the summer months (June to September/October) on northern breeding grounds, often leaving the country entirely, with only a few small resident populations remaining within the US. This means their contact with domestic poultry during summer is relatively limited.

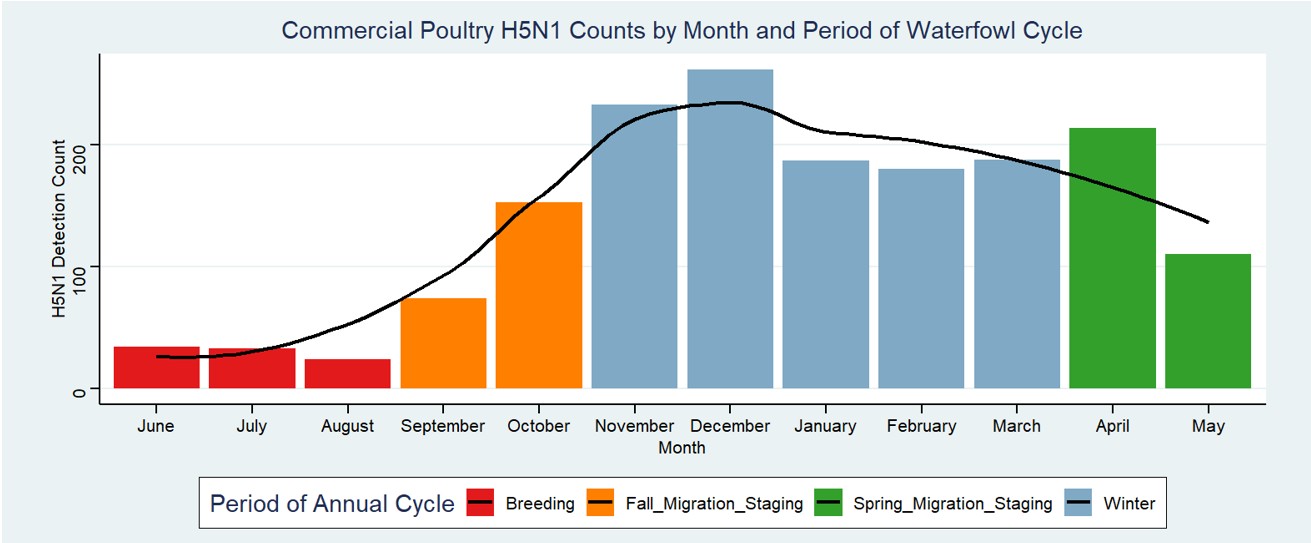

HPAI cases tend to rise in April and May, coinciding with their northward migration, then peak again from October through April during their southward migration and overwintering periods within the US (Figure 2). Compared to some dabbling ducks, diving ducks are more often true long-distance migrants, frequently traveling beyond US borders, which plays a significant role in the seasonal dynamics of disease spread.

Figure 2. Annual cycle of H5N1 detection counts

Flyway patterns, high-risk zones

Diving ducks follow diverse migratory routes and utilize a wide range of habitats, depending on species and geography throughout their annual cycle. Despite these differences, they collectively shape a continental pattern of HPAI risk.

By understanding how risk varies by diving-duck species, flyway and season, farmers can better anticipate times of heightened threat linked to diving-duck and other waterfowl movements and apply targeted biosecurity measures to safeguard their operations (Figure 3).

Here is the breakdown of general diving-duck trends by flyway:

Pacific flyway

Diving ducks migrate north in spring through the Central Valley (e.g., Sacramento Valley), Klamath Basin and Puget Sound. They breed in deep lakes and coastal zones across Alaska, British Columbia and the Yukon. Fall brings them to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, Great Salt Lake and San Francisco Bay. In winter, they concentrate in estuarine and freshwater systems along coastal California and the Pacific Northwest, elevating HPAI risk.

Central flyway

Spring routes pass through the Nebraska Sandhills and Oklahoma wetlands, with breeding in the Prairie Pothole Region and lakes like Devils Lake. In the fall, they use large reservoirs (e.g., Lake Sakakawea) and river systems like the Missouri. Wintering occurs along the lower Mississippi and Gulf Coast wetlands, which are key for monitoring HPAI spread.

Figure 3. Flyway patterns

Mississippi flyway

Migrating north via the Mississippi River, divers breed in northern US lakes and Canadian wetlands (e.g., Lake Winnipeg). In fall and winter, major sites include Illinois River backwaters, Mille Lacs Lake and coastal Louisiana (Lake Pontchartrain, Mississippi Delta), where dense flocks heighten HPAI transmission risk.

Atlantic flyway

Diving ducks move north in spring through Chesapeake Bay and the Great Lakes, breeding in New England, Quebec and the Maritimes. Fall and winter see concentrations in estuarine waters like Delaware Bay, Long Island Sound and Penobscot Bay, with the Chesapeake Bay remaining a key overwintering area.

Figure 4. Real-time tracking

Forecasting movement in real time

To better anticipate and respond to HPAI threats from migratory waterfowl, the WaterFowl Alert Network, developed by AgriNerds, provides real-time forecasts of waterfowl movement across the US. The tool highlights high-risk zones on the landscape, including rivers, lakes, quarries and estuarine bays, areas where waterfowl often concentrate and where the potential for virus transmission is elevated (Figure 4).

By integrating weather radar, GPS tracking and environmental data, the system equips poultry producers, conservationists and wildlife managers with actionable, location-specific insights. This enables proactive decisions around biosecurity and habitat management, especially during migration and overwintering periods when risk is highest.

References

- Densmore CL, Iwanowicz DD, McLaughlin SM, Ottinger CA, Spires JE, Iwanowicz LR. Influenza A Virus Detected in Native Bivalves in Waterfowl Habitat of the Delmarva Peninsula, USA. Microorganisms. 2019;7:334.

- Ma W, Ren C, Hu Q, Li X, Feng Y, Zhang Y. Freshwater crabs could act as vehicles of spreading avian influenza virus. Virol J. 2021;18:246.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

Feature photo credit: Matthew Hardy