Good composting procedures eliminate odors and reduce the number of flies, rodents, predators and scavengers attracted to the bins. Additionally, when done properly, composting is a cost-effective method of biosecurity that prevents the spread of disease.

“Proper composting of dead birds is important on poultry farms but is often overlooked,” said Ray Hilburn, associate director of the Alabama Poultry and Egg Association.

“The main issue with compost bins on poultry farms that I see is moisture leakage, which causes odor. Either there’s not enough litter to absorb the moisture, or the birds are placed too close to the bin sidewalls, leading to moisture leakage,” Hilburn noted.

Another common problem Hilburn encounters is that the primary compost bin is too large, causing hilling of the material rather than proper layering. Hilling doesn’t allow the compost to reach and maintain the necessary temperature.

Hilburn compares good composting techniques to building a layer cake: To reach the necessary temperatures for decomposition, everything must be even and flat. He also noted that a primary bin and a secondary bin are needed for the complete breakdown of bones and feathers.

Proper composting strategies

Hilburn mentioned many recommendations for proper composting:

- Primary and secondary bins should be built on concrete.

- The litter stored for composter use can be on concrete or packed clay base.

- Primary bin size should be 5 feet (1.5 m) deep, 5 feet high (1.5 m) and 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3.6 m) long.

- Secondary bin size should be 5 feet (1.5 m) high, 5 to 6 feet (1.5 to 1.8 m) deep and 60 to 70 feet (18 to 21 m) long or longer, based on the number of primary bins.

- Four to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) of litter is needed as the first layer of the primary bin.

- Wet carcasses in a leak-proof bucket or container.

- Place wet carcasses in a single layer without wetting the litter more than necessary.

- Place birds no closer than 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) from the walls of the composter, and ensure birds are not piled on top of each other.

- Cover birds with litter at a 3 to 1 ratio (e.g., one 5-gallon bucket of dead birds to three 5-gallon buckets of litter).

- Use 3 to 5 inches (8 to 12 cm) of litter between layers, depending on the size of the birds.

- Continue layers until the bin is full, and cap off with a top layer of litter.

Wetting the birds before layering helps raise the temperature in the compost. A probe thermometer should be used to measure the compost temperature, which should reach 130° F to 140° F (54° C to 60° C).

“The temperature rise indicates the compost bin is doing its job,” Hilburn explained. Once the temperature peaks, it typically remains steady for 10 to 14 days before beginning to decline.

Hilburn warned that more litter will be needed to compost larger birds, noting that “Chickens are 60% moisture. Larger birds will release more liquids.” He recommended spreading out larger birds so that there is litter between the birds to absorb the additional moisture.

A rake can be used to even each layer. Hilburn advised leaving the material in the primary bin for at least 2 months before transferring it to a secondary bin. The secondary bin, he said, should be located directly behind the primary bins, allowing the composted material to be easily moved into the secondary bin with a front-end loader.

Once material is moved to the secondary bin, recapping with fresh litter helps raise the temperature, enabling the remaining bones and feathers to break down. Because most of the decomposition is complete, Hilburn explained, the secondary bin material doesn’t need to be layered. Instead, it can be in a pile. He recommended leaving compost in secondary bins for at least 2 months.

“Good recordkeeping is important,” Hilburn emphasized. He suggested recording the date when material is first added to the new bin, noting each layer as it’s added, and logging the daily temperatures taken at two different locations in each bin. He also records when the primary bin compost is transferred into the secondary bin and when it is spread onto a field.

Reducing potential spread of bird flu

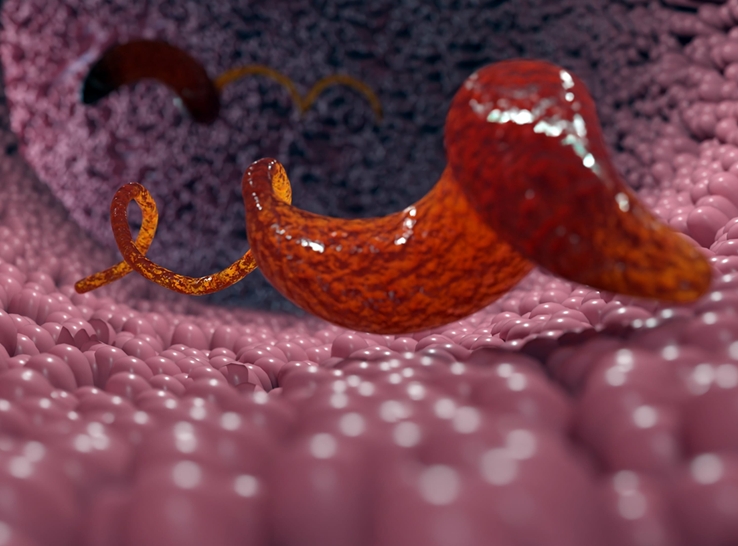

The abundance of avian influenza (H5N1) in wild-bird populations and efforts to reduce its spread are front of mind throughout the poultry industry. Taking every possible measure to avoid attracting vultures, which are known carriers of bird flu, has taken on renewed importance.

Infected vultures that land around farm compost sheds expel the H5N1 virus in their feces, which can then be tracked into the poultry houses, said Joel Cline, DVM, Wayne Sanderson poultry veterinarian.

Turkey vultures can smell rotting carcasses from over a mile away. Black vultures use their eyesight to locate potential food sources and often follow turkey vultures to carcasses. Cline noted that there is a big difference between exposed rotting flesh that produces odors and attracts vultures and properly composted birds, which are covered and do not produce odors.

Diligence is needed to thwart vultures’ keen senses so they are not attracted to farm compost bins. “Continuously inspecting compost sheds enables corrective action,” Cline said. He described six things to watch for and improve:

- Evidence of vultures or wild birds: Carcasses, black feathers, tracks, live wild birds and feces all indicate that the compost shed is attracting wild birds.

- Vermin and other predators: Rodents and other scavengers can dig through compost, exposing carcasses and releasing odors. Unkept grass, weeds and stored equipment provide places for vermin to live and hide. Therefore, the area surrounding compost bins should be kept neat and clean.

- Exposed flesh in compost: Cover carcasses completely and immediately.

- Leaking liquids: Liquids leaking from bins will smell and attract scavengers. Ensure compost boards remain dry and the proper ratio of litter to dead birds is maintained.

- Compost is layered in the primary bin rather than piled: Layering ensures proper heating and decomposition. (Secondary compost bins can be piled.)

- Good biosecurity measures.

“The compost shed is a high-risk area on the farm,” Cline said. “Be aware of this risk and the importance of using good biosecurity before going back into the houses, including using the footbath every time!”

The presence of buzzards on farms has been linked to several outbreaks of avian influenza. Thus, it is imperative that compost sheds are properly maintained to control odors and prevent attracting vultures.

Cline emphasized, “The best way to discourage wild birds from visiting the farms is to eliminate their food source. No food equals no birds!”

Cline and Hilburn noted that the Alabama Poultry and Egg Association has an excellent video about composting, which can be viewed here.