Minimizing the concentration of mycotoxins in feed is key to preventing necrosis of the oral mucosa and esophagus, which decreases the ability of the digestive tract to digest and absorb nutrients.

The condition also renders poultry more susceptible to bacterial pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, according to a report co-authored by Gino Lorenzoni, DVM, PhD, assistant professor of poultry science and avian health, Penn State University extension service.

The report also warns of producers about the immunosuppressive effect of mycotoxins. In general, large doses of mycotoxins such as ochratoxin and trichothecenes will lead to lymphocytic depletion in immune organs, meaning reduced immune function overall.

Reduced immune function, they add, can also occur when contamination of feed occurs from different mycotoxins simultaneously, even if concentrations are below the respective maximum threshold individual mycotoxin.

“This is due to cooperative activity that occurs when several mycotoxins are fed at the same time,” the report explains. “Depression of immune cells occurs along with inflammation on different organs renders several tissues more prone to bacterial and viral contamination.

“As a rule of thumb, after monogastrics have been consuming feed with contamination levels of mycotoxins, they will be more susceptible to infections and disease.”

Source of mycotoxins

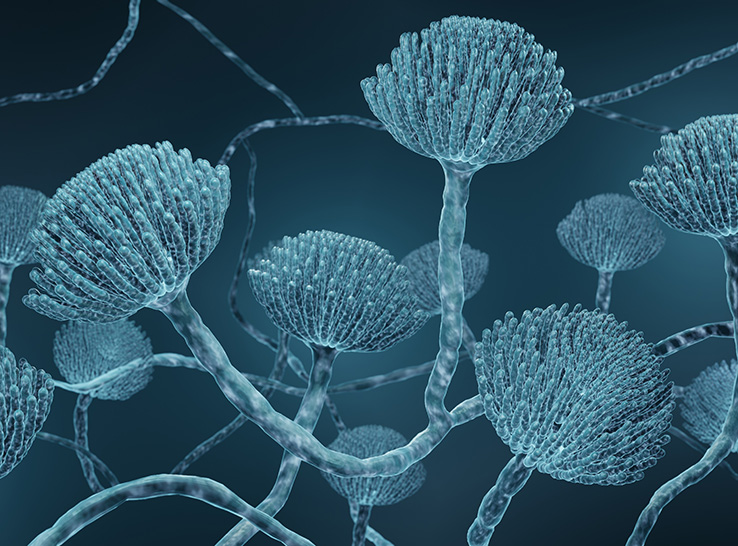

The fungi that produce mycotoxins are commonly present in crops. This is especially so in hot, humid weather. If it’s rainy weather during harvest, crops contain more mycotoxins compared to crops harvested in drier weather, the authors say.

Grain is more likely to contain mycotoxins if it’s left out, exposed to the elements, or stored in dirty silos or bins. Grain stored for more than 7 days in bins and silos is more likely to contain mycotoxins.

Metal walls of silos or bins in hot weather conduct heat that is transferred to grain and when the temperature cools, condensation builds up. “Humidity and heat in the presence of mold contamination on the walls of a dirty silo are the perfect environment for mold growth and mycotoxin production,” they explained.

To minimize mycotoxin exposure, poultry feed needs to be stored in clean silos or bins, but really needs to start soon after harvest.

Remove or dilute contaminated kernels

Removing heavily contaminated kernels, which are considerably lighter than kernels in noncontaminated grain, is also critical, the specialists say. Contaminated kernels can be removed with a grain separator that uses air flow to raise and separate light from undamaged kernels.

Contaminated grain can also be diluted with uncontaminated, high-quality grain.

“In general, there is a range for most mycotoxins at which they start affecting the animal production in a significant manner. If mycotoxin affected grains must be used, dilution of the affected batches of grain is a cost-effective measure for reducing the impact of mycotoxins on livestock consuming that grain,” according to the article.

The authors note that multiple sampling and mycotoxin analysis are needed to determine the concentration of mycotoxin in every batch of feed, which makes this approach impractical for feed manufacturers.

Mycotoxin binders

If diluting mycotoxin-contaminated feed isn’t sufficient, mycotoxin binders is another way to minimize poultry exposure to mycotoxins in feed.

Generally, non-polar or the aflatoxin type of mycotoxins are effectively bound by mycotoxin binders. Although most mycotoxin binders can also bind nutrients, this shouldn’t be a concern if binders are only used for a short time, the authors say.

However, “Products that offer ability to bind or deactivate toxins other than aflatoxin should be cautiously evaluated and require further inspection,” they caution. Some of them are not only more expensive, they also have not been tested in live animals.