Dealing with mycotoxins in poultry feed ingredients is nothing new, yet it remains a challenge that needs more answers.

“We tend to think about mycotoxins when we receive affected ingredients at the feed mill, but a lot happens before that point,” said Todd Applegate, PhD, assistant dean for international programs and department head of poultry science at the University of Georgia.

One characteristic that makes mycotoxins so challenging is their ability to grow on any organic substance, especially cereal grains. Also, mycotoxins are resistant to feed milling processes, which means the contamination can become ubiquitous throughout the food chain.

In a Poultry Science Association webinar, Applegate shared his findings of a literature review on mycotoxins and discussed future research needs.

Understand the differences

“When we hear the word ‘mycotoxin,’ we tend to think of them as all the same. But mycotoxins are very different metabolites, and the strategies to deal with them and to mitigate risks are very different,” he said.

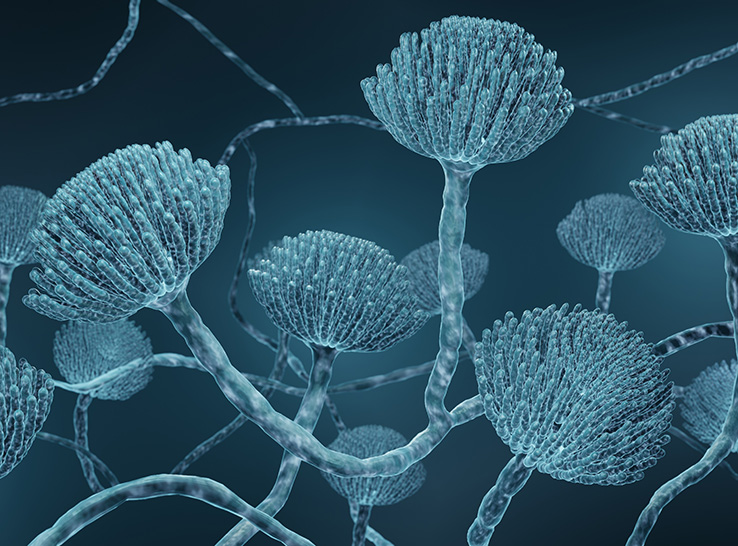

There are three major species of mycotoxin fungi:

- Aspergillus is mainly a storage toxin that produces aflatoxin.

- Penicillium is also related to improper storage and produces ochratoxin, which impacts poultry.

- Fusarium tends to occur in the field and produces trichothecene T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON), fumonisin and zearalenone.

Mycotoxins have a global reach. The Americas and Europe primarily deal with DON, fumonisin and zearalenone, while Southern and Southeast Asia often have more aflatoxin, Applegate noted. “The only real difference is the percentage of samples that reach risk-level concentrations, and if you import ingredients, some storage mycotoxins may develop.”

He pointed to three dosage levels cited in the literature. The first two listed below reflect the “operational range” and are the focus for production purposes:

- Realistic dose is a common dosage and is what occurs annually.

- Occasional dose develops under unfavorable conditions, often weather related.

- Unrealistic dose is an experimental dosage to look at the mechanistic role mycotoxins create. “We don’t need to consider this in the real world,” he added.

“When it comes to toxicity, we need to think about the consumption and dosage over time,” Applegate emphasized. “For example, the operational range for aflatoxin is 0.3 to 2 ppm, but we know in broilers, if we feed 2 ppm for a couple of weeks, it will curb the bird’s weight gain by 25%.”

Poultry nutritionists and producers need to appreciate the difference between a realistic dose and an extreme dose for various mycotoxins, he said.

Impacts on poultry

It’s rare to see clinical symptoms of mycotoxin in birds, but it’s good to recognize them, Applegate noted. Kidney damage, fatty liver, leg weakness, impaired feathering, wide size variations within a flock, beak ulcers and gizzard lesions are clinical outcomes.

More commonly, the impact is broken down into four phases:

- Phase I is a dose/response effect. “As the dose increases, there will be some reduced growth and impaired immunity,” he said.

- Phase 2 increases susceptibility to subclinical symptoms.

- Phase 3 will produce overt immune suppression and clinical toxicity.

- Phase 4 will result in death as toxic metabolites accumulate.

Phases 1 and 2 encompass most poultry cases associated with realistic and occasional mycotoxin doses. Applegate explained that it’s important to understand where specific mycotoxins are absorbed by the animal, noting that 80% to 90% of the dose for DON, aflatoxin, zearalenone and ochratoxin A is absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Notably, aflatoxin is by far the most readily and efficiently absorbed mycotoxin, at greater than 80%.

“Enterohepatic circulation may increase exposure of DON, zearalenone, fumonisin B, T-2 toxin and ochratoxin A all along the GI tract,” he noted.

A meta-analysis by Brazilian researchers reported that, across all mycotoxins, the feed intake reduction is nearly 12%, but 23% for aflatoxin. Mycotoxins can reduce bodyweight gain by nearly one-third. “That will vary depending on how much mycotoxin is present and in what combination,” Applegate said.

He also noted that mycotoxins will have a greater impact if the diet falls short of the bird’s protein and amino acid needs. “Keep that in mind, not only for low-protein diets, but also for things like subclinical intestinal enteritis issues that might affect feed intake or gut functionality.”

Mycotoxins do affect nutrient digestibility in poultry, but the effect is variable. “With aflatoxin, we see some drag in broilers for nitrogen and energy efficiencies and dry-matter digestibility,” Applegate said.

Because laying hens are longer living birds, toxins accumulate over time before the liver processes them. “We see more consistency in terms of nitrogen drags on digestibility and caloric inefficiencies in layer diets.”

Again, mycotoxin combinations will have a greater impact. “With combinations of two mycotoxins in the diet (i.e., DON and fumonisin), we see increased lesions and an increased presence of oocysts,” he added. “In necrotic enteritis models, we see the prevalence and induction of disease-associated lesions, even without the presence of Clostridium perfringens.”

Climate change impact

When reviewing mycotoxin research, climate change must be part of future discussions as more extreme weather and shifting patterns become commonplace. “We are seeing changing weather conditions, as local weather impacts the prevalence and occurrence of mycotoxins,” Applegate said. “Realize that nearly 95% of toxin formation occurs in the field and is greatly influenced by the weather, temperature, moisture and growing conditions.”

He pointed to the Horizon 22 Project (2016 to 2022), which involved scientists across 23 public and private partners in 11 countries to consider mycotoxin predictions for corn and wheat.

“They evaluated four primary mycotoxins to try to develop robust risk-management and mitigation strategies, using weather patterns to determine if mycotoxin development could be predictable at the field level,” Applegate said.

For corn, the mycotoxins were aflatoxin, zearalenone, fumonisin and DON. For wheat, they included zearalenone and DON. The project resulted in predictive tools that were used in some commercial poultry production practices.

“Looking at the results, 120 days before harvest and 10 days after, there was a very high correlation between weather patterns — whether it’s temperature or precipitation — on the occurrence of aflatoxins,” he relayed.

The study provided weather data that can be used with known correlations of mycotoxin development and concentrations. For example:

- Aflatoxin occurs under warm and dry conditions.

- Fumonisin levels increase under warm and dry conditions.

- Fusarium toxins correlate with lower temperatures.

- Zearalenone develops when the weather is colder and more humid.

- Ochratoxin A mainly occurs under dry and windy conditions.

“That information provides us with evidence of what we can do to predict and prevent mycotoxin formation,” Applegate said. “I think we can use predictive models to maximize the harvest timing window in the face of an expected weather event, and then make ingredient-purchasing decisions.

“In the future, we will also need the exact geolocation of samples to improve those models further. We will still need mitigation strategies, and those become very complicated.”

Mitigation strategies

There is a wide range of mitigation options, but their application depends on the specific mycotoxin. As noted, because most mycotoxins develop in the field, predictive tools are needed to inform agronomic decisions, but Applegate isn’t sure that’s been happening.

“Research has shown us that monoculture crops such as corn over multiple years leave fungal spores in the field, which increases the baseline mycotoxin risk,” he said. “Organic matter left behind, such as with low- or no-till, also leaves fungal spores for the future crops.”

There’s substantial evidence that fungal resistance builds up within crop varieties, so that should be considered when selecting varieties for crop rotation.

“Similarly, some fungicides used in agronomic practices build resistance. We need to formulate new strategies for fungicide development, as well as site-specific application procedures and timing to slow that resistance,” Applegate said.

Harvest timing impacts mycotoxin development, and integrating effective pre- and post-harvest strategies is needed. One such example is knowing baseline mycotoxin levels so that grain can be screened and cleaned before entering storage. “Or, if we know there’s a high mycotoxin incidence in corn, for example, it could move to ethanol production,” he noted. “Ethanol fermentation will lower toxin levels in distiller’s grain co-products. Also, we could strategically include hydrolytic enzymes for some mycotoxins.”

As poultry producers acquire ingredients from different sources, Applegate said there are three buckets that current and future mitigation strategies fall into:

- Physical methods involve separation, applying seed-sorting technology before storage. “Some field mycotoxins create differences in seed weight, and we could segregate those as they go into storage,” he noted. “Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are working on this.”

- Chemical methods to denature some of the metabolites — ammonization, for example. “These options have not been widely adopted due to cost,” he said.

- Biological methods involve developing biomarkers to detect poultry mycotoxin exposure and damage in real time. Most damage is determined after the fact, based on production declines. “Not many people have looked at biomarkers, but it’s gaining traction,” he added. “We need to have biomarkers in hand as we move forward with mitigation strategies.”

Because poultry feedstuffs are purchased from multiple sources and regions, it would be beneficial to maintain crop identity. “The difficulty is in retaining the crop identity throughout the value chain. You may have that information at the local source, but as grain loads into rail cars, we lose a lot of that ability,” Applegate said. “Integrating that information is key to a robust risk-management process. Without taking full advantage of logistics, we will be limited. So, we focus on mycotoxin control at the feed mill.”

Feed additives

Adding adsorbents or binders to feedstuffs has become a common mitigation option. But factors such as pH and the binder’s ability to adsorb or bind to a specific mycotoxin influence the outcome.

“We cannot treat all mycotoxins the same when using a singular adsorbent in the diet,” Applegate said.

For example, aflatoxin tends to respond well to adsorbents, but DON or T-2 toxin less so. Inorganic binders or organoclays generally have high adsorption, but more variance occurs with organic binders. “Those with high ash content are better adsorbed, but other organic binders have not been consistent over time,” he noted.

Other options include plant extracts such as silymarin, which offers a biological protective role. It is often included with aflatoxin adsorbent materials to protect the liver. “Antioxidants also fill some of these roles, by providing a protective layer across all gut-health modifier categories,” Applegate added.

Enzymes can detoxify mycotoxins by converting them into less toxic compounds. “In past years, most enzymes came from cattle rumens or soil, and it was a hunting expedition to find the right microbe and the right enzyme. This took a long time,” he said. “Today, predictive next-generation sequencing, functional metagenomics and genetic engineering have shortened that timeline.”

Applegate offered these pros and cons of using enzymes to address mycotoxins:

Pros:

- Enzymes have very high specificity.

- They have relatively high efficacy. The degradation is rapid and irreversible if they work high in the digestive tract, before the mycotoxin is absorbed.

- They preserve dietary nutrients. “Adsorbents, on the other hand, can bind and sequester such things as vitamin B or micronutrients,” he added.

- Enzymes are safe for animals, humans and the environment.

Cons:

- Stability can be variable. “We have to think about stability through milling systems as well as the bird’s GI tract,” he said.

- The reaction condition —how much water, oxygen, pH, temperature and time are required to create a favorable reaction.

The challenge with any mitigation options today is that the economics are not connected to the value-added chain, Applegate pointed out. Consequently, adoption of some strategies falls short because return-on-investment (ROI) details are lacking.

Risks and future direction

Looking ahead, Applegate outlined areas that require more answers and direction.

- Research, specifically focused on the realistic and occasional doses poultry nutritionists and producers encounter, and not on unrealistic levels.

- Biomarkers must be very specific to the mycotoxin, have a short response timeline and be easy to analyze.

- Modes of action — “We need to understand better the mycotoxins’ effect on the bird’s physiology and immunology, especially with control of the inflammation process,” he said.

- Detoxification ontogeny — how an organism detoxifies harmful substances from a developmental standpoint through its life stages — is mycotoxin-dependent and has had little study. “We need to understand those processes, which could also benefit the understanding and use of mitigation strategies,” he added.

- Mitigation strategy development, specifically the need to shorten the timeline and ensure strategies are mycotoxin-specific.

- Economic evaluation of intervention strategies, including when and where combinations would best produce results. In other words, the ROI of applying an intervention versus the risk exposure.

- Define site-specific field interventions to limit the development of fungicide resistance, such as crop rotations and cultivation practices, and how to apply that back to the farmer. Also, develop new fungicides with greater specificities for future mycotoxin trends.

“There are currently some good examples of prevention and mitigation strategies, particularly in the field,” Applegate concluded. “But we, as poultry scientists, need to reach out to other areas of the value chain to have the conversation and think more systematically about how best to address mycotoxins.”