By W. A. Dozier, III, PhD

Department of Poultry Science

Auburn University and

Alabama Cooperative Extension System

Life-of-flock hatchability has declined from approximately 84% to 79% in the US over the past few years. In concert with increased broiler mortality, this decrease in hatchability has led to fewer broilers entering the processing plant, resulting in a loss of revenue for integrated poultry operations.

Life-of-flock fertility plays a significant role in the number of hatching chicks placed, and managing the male from rearing through production impacts breeder flock performance.

Proper feeder management and nutrition during lay can influence fleshing and bodyweight (BW) control, fertility and feed distribution, all of which significantly impact reproductive performance.

Factors of male management

Several factors are key to managing males during lay:

Bodyweight

Weighing males is important to manage the flock to control BW. It is recommended to weigh approximately 40 males (10 per location) in each house weekly until 31 weeks of age (WOA), and then biweekly thereafter until 60 WOA.

Males should be weighed in multiple locations throughout the house to obtain a representative sample of BW. Feed changes can be made according to BW until 31 WOA.

Fleshing

Fleshing — the process by which birds develop muscles on their breasts and wings — is very important. It is a good practice to assess fleshing in males while they are being weighed and to score males for fleshing weekly.

Fleshing should determine feed changes beyond 31 WOA to minimize the occurrence of over-fleshed males. If we do not observe a few males that are over-fleshed in a flock, then a higher occurrence of under-fleshed males may be observed.

Body condition

Loss of body condition in males impacts fertility in the lay cycle. Males should not be over-fed early in lay and then underfed, as this can worsen body condition and lead to poor fertility.

Testes weight

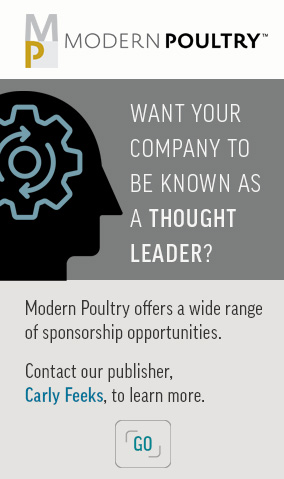

From 28 to 31 WOA, 35 to 50 grams of testes weight is optimum for semen production (Figure 1). Importantly, a more uniform flock will impact testes weight. However, if increases in feed allocation from 21 to 31 WOA are not implemented appropriately, roosters will start losing weight, leading to reduced testes weight and fertility.

Appropriate increases of feed allocation are needed from move (21 to 22 WOA) until 31 WOA, ensuring gradual increases in BW that will promote optimum testes weight and semen production. From 32 to 60 WOA, smaller increases in BW will help minimize over-fleshing.

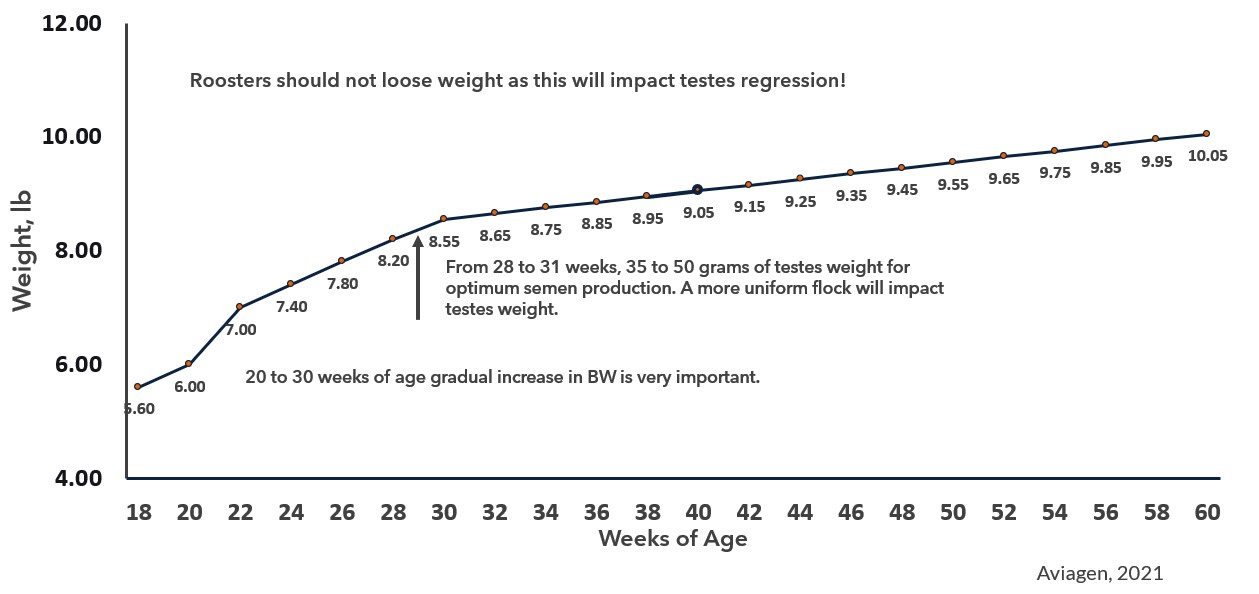

Powley et al. determined that males at 35 WOA vary in BW and fleshing.1 The study reported that testes weights were numerically lower with poorly-fleshed and over-fleshed males compared with males with adequate fleshing (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Projections of Yield Plus Aviagen male bodyweights from 20 to 60 weeks of age. Gradual increases in bodyweight are important from 20 to 31 weeks of age for optimum semen production, with smaller incremental increases in bodyweight from 32 to 60 weeks of age. Click figure to enlarge

Figure 2. Effects of bodyweight and fleshing on testes weight of male broiler breeders. Click figure to enlarge

Separate feeding of males

The benefits of providing a separate male diet include controlling BW and fleshing and increasing feed volume to improve feed distribution.

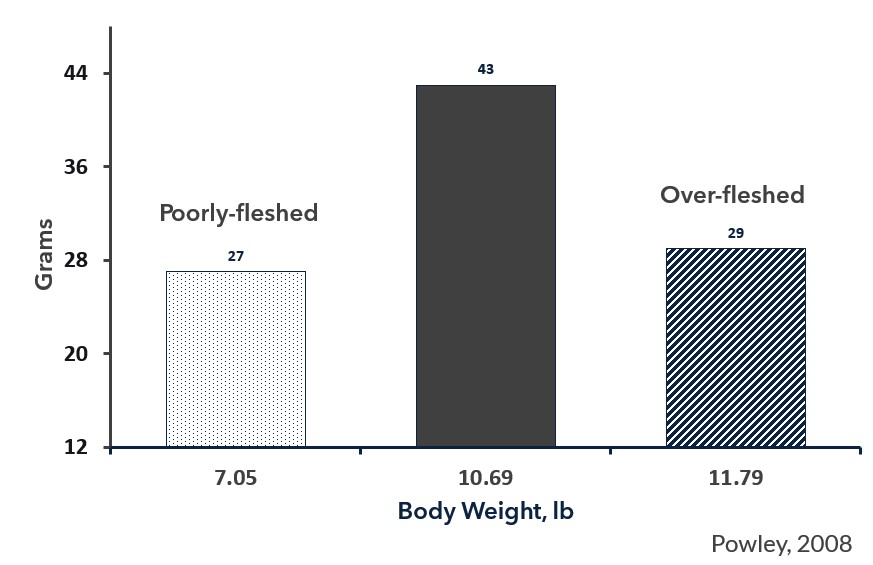

Gaynor McDaniel, PhD, Auburn University, and Gerald Bailey, Gold Kist, conducted field trials of male separate feeding in north Alabama in the early 1980s.2 They fed roosters a diet formulated to 1,290 kcal of metabolizable energy (ME) per pound and 11.9% crude protein, with a feed allocation ranging from 26 to 28 pounds per 100 birds from 25 to 53 WOA.

McDaniel and Bailey observed better BW control and fertility when roosters were fed a separate male diet than a diet formulated for breeder hens (Figure 3).3 At 52 WOA, there was an 8% increase in fertility and hatchability. The benefit of increased fertility occurred from 42 to 53 WOA.

In agreement, Silveria et al. evaluated the effects of feeding a separate male diet on BW, hatchability and fertility with 26 commercial flocks from 28 to 65 WOA.4 Fertility increased by 1.47% and hatchability increased by 4.17% when feeding a male-separate diet rather than a breeder hen diet.

Figure 3. Effects of feeding a separate diet formulated for roosters on fertility and hatchability from 25 to 53 weeks of age. Dr. McDaniel, Auburn University, and Gerald Bailey, Gold Kist, conducted field trials of male separate feeding in 1982 at a commercial complex in Alabama. Roosters were fed a diet formulated to 1290 kcal ME/lb and 11.9% crude protein with a maximum feed allocation of 26 to 28 lb/100 birds. These authors found better bodyweight control, increased fertility and hatchability. Click figure to enlarge

Additional feeding considerations

Dietary lysine, compared to other essential amino acids, has a higher percentage relative to crude protein in breast-muscle protein. Hence, dietary lysine can lead to over-fleshing in roosters.

Compared to hens, roosters need lower amounts of dietary amino acids to minimize the incidence of over-fleshing. For example, digestible lysine concentration should be only 0.35% to 0.50% for roosters, whereas a hen diet can contain 0.60% to 0.65% digestible lysine.

ME intake is another important dietary consideration for roosters. ME intake of roosters has been estimated to range from 331 to 382 kcal per day from 25 to 60 WOA.5

The modern rooster has a high percentage of lean body tissue. Energy is required to maintain adequate body condition with protein accretion and turnover, and the BW of these modern males have increased.

Roosters should consume an adequate amount of energy to support target-weight increases throughout the lay cycle. If they are not gaining incremental weight throughout production, testes weight will regress along with reduced fertility.

It is paramount that roosters and hens consume an adequate amount of amino acid and ME. In addition, it is very important to track amino acid and caloric intakes throughout the production cycle.

Finally, nutrient variability can influence maintaining target BW and control the amount of fleshing in males. Thus, it is vital to appreciate the nutrient variability with ingredients. Coupling ingredient variation with feeder space and feed distribution significantly impacts rearing and production to overall reproductive performance.

Implementation limitations

Even though there are advantages associated with BW control, fleshing and fertility with separate male feeding, most of the US does not currently have the infrastructure to implement feeding a separate diet for males.

Breeder farms can be equipped to implement a separate male feeding program, which requires feed bins, scales, fill lines and augers. Factors to consider when implementing this feed program include bin storage space at the mill, transportation logistics and transportation costs of delivering male feed to breeder farms.

Growers and service technicians will be required to manage two feed types on the farm. The mill may consider adding dyes to the rooster feed to avoid the mistake of hens receiving the male feed, which could create reproductive performance issues and an incidence of calcium tetany.

Feeder management

Restriction of female feeders is important to prevent mature roosters from consuming hen feed to minimize excessive BW and over-fleshing. Check feeder guards to ensure roosters are locked out of hen feeders by 24 WOA. On the other hand, feeders should be set to be 18 inches from the floor to avoid hens consuming rooster feed.

Feeder space and feed distribution are important to allow all the roosters to consume adequate amounts of nutrients, as cleanup times may be only 30 to 45 minutes. Adequate feeder space is especially important so that timid males can receive an adequate intake of nutrients.

Each pan needs to provide similar amounts of feed, but an uneven floor in the scratch area can limit access to feeder pans. Hence, it is critical to ensure the floors are even so roosters can access all feeders in the house, with the goal of providing optimum intake of nutrients to all of the roosters.

Finally, it is imperative to ensure an accurate weighing of feed. Scales need to be routinely calibrated so that an accurate feed weight is being delivered to the house.

Key takeaways

- Start feeding separate rooster diet at 25 WOA. However, the realized benefits may not occur until 40 WOA.

- A 1.0% to 2.0% increase in fertility can be obtained through diet, and larger improvements may be observed after 45 WOA.

- Advantages of implementing a separate male diet include increased feed volume, fertility and control of BW and fleshing.

1 Powley J. Testes development and fertility. Ross Tech Notes. 2008 June.

2 Hudson B. Raising today’s broiler breeder: Feeding from start to finish. US Poultry and Egg Hatchery Breeder Clinic, Nashville, TN. 2023.

3 Ibid

4 Silveria MM, Freitas AG, Morales CA, Gomes FS, Litz FH, Martins JMS, Fagundes NS, Fernandes EA. Feeding management strategy for male broiler breeders and its effects on body weight, hatchability and fertility. Brazilian J Poult Sci. 2014 Dec;16(4):397-402.

5 Aviagen. YP × Ross 708 Rearing/Breeding Program. 2021.

Editor’s note: The opinions and/or recommendations presented in this article belong to the author and are not necessarily shared by Modern Poultry.