By Marcelo Lang, DVM*

Farsight Consulting & Marketing Services, LLC

When I started my career in the animal health industry in the mid-1980s, using antibiotics in the feed to enhance gut health and improve performance was considered to be a good thing. It was also approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and most international regulatory agencies.

Why administering some antibiotics resulted in better feed conversion and growth rates wasn’t clear, but the consensus was that a healthier gut from the antibiotic led to better feed absorption and utilization. This occurred so consistently that some antibiotics actually had performance claims.

Other antibiotics used for disease, including ionophores, didn’t claim improved performance on the product label, but it was obvious to many that flocks given certain medications for enteric diseases got to market faster on less feed.

In the US, that all changed in 2017, when the FDA withdrew performance claims on any animal antibiotics that were also used in human medicine. Performance claims were still allowed for some feed antibiotics used in animals only (e.g., bacitracin). But even then, some global animal health companies decided not to pursue performance claims for new animal-specific medications.

Focusing on medicinal claims

By the time I got involved in launching avilamycin, the last antibiotic approved by FDA for use in chickens (that was 10 years ago), I joked to our regulatory affairs people that we might want to promote our product’s growth-enhancing effects as “adverse events” and print the following on the label: “Warning: The use of this drug may cause increased daily weight growth and/or improved feed conversion.”

They didn’t see any humor in my suggestion, however, and chose to register the product only with a medicinal claim (necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens). Ultimately, the marketing team conceded that limiting the label to medicinal claims would be more in step with consumer demand and the industry’s antibiotic stewardship goals. From a practical standpoint, our friends in regulatory affairs also thought this more streamlined approach might help to speed up the FDA’s approval.

All things considered, I believe the poultry industry and animal health companies did the right thing when moving in this direction. It showed sensitivity to ever-increasing concerns about antimicrobial resistance (AMR), even though most incidences occurred in humans, not animals. There was also growing societal pressure — from governments and consumers — to use antibiotics more judiciously, if at all, without compromising flock welfare.

Race to find alternatives

Europe got an even earlier start on this initiative. Since the EU’s total ban on antibiotic growth-promoting claims in 2006, the race to find suitable alternatives has intensified. Even before that, when only some antibiotic groups had been banned, researchers reported an increased incidence of bacterial infectious diseases, such as Escherichia coli diarrhea in pigs and clostridial necrotic enteritis in broilers.

Fast-forward 20 years, and we now have product categories that, at the time, were nonexistent or considered fringe by the mainstream. Probiotics, botanical extracts, essential oils, glycerides and others were initially met with heavy skepticism by poultry nutritionists and veterinarians.

While some skepticism remains (and probably for good reason), a recent study of scientific publications shows an enormous output of research papers exploring potential alternatives to antibiotics to promote growth and health in poultry. Some estimates suggest that at least 80% of broilers raised without antibiotics receive one or more “alternative” feed additives to prevent gut health problems.

Phage therapy

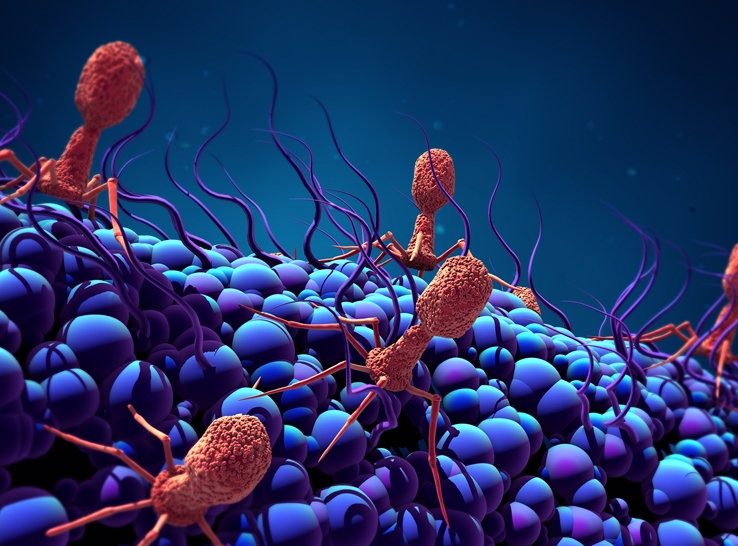

Before antibiotics were even discovered, another option that had been studied for treating infectious diseases in humans and animals was “phage therapy,” which refers to the use of bacteriophages (phages) as a therapeutic agent.

Phages are small viruses that can target and eliminate specific bacterial strains without compromising other microbial species within our bodies. Bacteriophages are self-replicating and self-limiting because they multiply only when bacteria are available.

Phage therapy for poultry and livestock has been slow to develop commercially, probably due to the effectiveness of current antibiotics. But many scientists are giving it a second look. Why is this happening now? There appears to be a combination of several factors.

First, and most importantly, scientific research has finally shed some light on phages — how to identify them and what they can do. Finding the right phages to combat a specific bacterium can take time. To find a phage that can kill a specific bacterium, you need to test libraries of phages for the ones with the strongest interactions.

New artificial intelligence methods use machine-learning algorithms to make this process easier. This approach is only becoming possible now because of the large datasets that can be used to train and test machine-learning algorithms and ultimately identify phage–bacterial matches. Of course, computational predictions still require validation, and more data will be needed to move forward, but these methods can help by narrowing the search.

Many countries in Eastern Europe have used phage therapy for more than 100 years. In contrast, in Western Europe, phages are primarily used on compassionate grounds — i.e., in life-threatening situations, when all other treatments have been exhausted. The history of the discovery and use of bacteriophages is as intriguing as a spy thriller. (To learn more about their fascinating story, check out a video by Patrick Kelly, a science writer and educator.)

Tailored to individual bacteria

Phages are highly specific to their bacterial hosts. They do not infect human or animal cells but can kill bacteria that cause disease without disrupting the body’s normal microbiota or causing significant side effects.

Phage therapy can be tailored to individual bacterial infections, particularly those resistant to antibiotics. Phages can be combined to create mixtures that can target most common diseases. They can also be used in conjunction with antibiotics to enhance treatment efficacy, particularly against infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In veterinary medicine, phages can be used to treat infections in livestock and companion animals, thereby reducing reliance on antibiotics and decreasing overall antimicrobial consumption, a key factor in the development and spread of AMR. In lyophilized form, the phages can be administered via the drinking water or the feed. They can also be administered intravenously to combat systemic infections, but this route may not be practical for most veterinary uses.

Some phages target foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella enterica in poultry and E. coli in cattle, reducing infections without relying on antibiotics.

We should also note that bacteria can develop resistance to phages, just as they can to antibiotics, but phage-resistant bacteria are often less harmful. In response, phages can evolve, which can increase their effectiveness again. Phage therapy holds promising potential for specific bacterial infections but cannot be used universally against all diseases.

Weighing the risks

Phage therapy is generally considered safe for the host animals because phages do not target animal cells. However, they interact with cells that can take them up, which could be a valuable way of targeting intracellular bacteria. Nonetheless, there are some risks because, like antibiotics, phages can cause the release of endotoxins (toxic substances from bacterial cell walls), leading to inflammatory responses, especially in large-scale infections.

We know that a focus on preserving animal health is an important strategy for preventing foodborne pathogens. Several pathogens can infect poultry asymptomatically, leading to contamination and public health hazards. The most common bacterial pathogens of poultry against which phages can be deployed are Salmonella spp., E. coli, Campylobacter spp. and Clostridium spp.

Currently, in the US, poultry bacteriophage products are only available as post-harvest sprays to reduce contamination with specific pathogens. Many phages are “generally recognized as safe” by regulators, which simplifies the registration process. These phages readily reduce bacterial levels in food products and surfaces and can enhance a multi-hurdle approach to improve Salmonella control and food safety. As a result, these features make bacteriophages a beneficial intervention to target Salmonella in poultry. Most phage applications result in 1- to 3-log reduction in bacteria, providing significant health and food safety benefits.

Use in live poultry

Finally, there is the tantalizing possibility of developing and adopting phage therapy to prevent or treat bacterial infections in live poultry. Although no products are currently commercially available, I am aware of several initiatives that may result in commercial phage products soon hitting the market.

For example, researchers at Purdue University’s College of Agriculture have developed a bacteriophage treatment that effectively reduces the colonization of avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) in treated chickens. Paul Ebner, PhD, head of the university’s animal science department, and his team isolated seven bacteriophages that showed activity against the most prevalent APEC variants.

“Taken together, they lysed 90% of the APEC strains we tested,” Ebner said. “When given to chickens, the treatment significantly reduces APEC in the treated chickens’ lungs and ceca. The treatments do not negatively impact growth or performance, and the birds do not develop an immune response to the phages.”

In Europe, several dossiers for bacteriophage products are under review. But to date, none has been authorized, either as a feed additive (European Food Safety Authority) or as a drug (European Medicines Agency). This situation may change soon, as at least one product is nearing the end of its approval process.

All these recent developments suggest that a new “Age of Phages” is coming upon us. The poultry industry stands to gain valuable new weapons to replace the depleted arsenal of drugs.

Experience tells me that once the first commercial product is launched, uptake will be slow, as poultry integrators and their veterinarians will most likely insist on testing it in their facilities before committing to a new type of intervention. However, provided that the products are effective, practical to use and not cost-prohibitive, I would be happy to see new solutions to recurring poultry health challenges.

*Dr. Lang is an industry trendwatcher with more than 35 years’ experience in poultry. After working for several animal health and nutrition companies, he opened his consultancy, Farsight Consulting & Marketing Services.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.