A precision poultry-feeding system developed by University of Alberta scientists has the potential to bring improved fertility, better flock uniformity and significant savings for broiler breeder producers, according to Poultry Science Association past-president, Martin Zuidhof, PhD, who is a professor at the university.

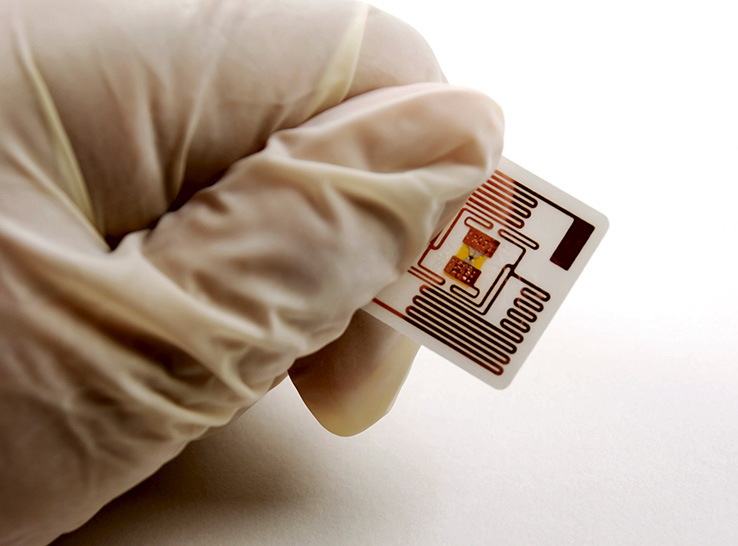

The system uses radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags embedded in birds’ wing bands to enable single birds to enter the feeding station. There, they are weighed and either granted access to feed or exited from the station based on where they are relative to their target weight. The two-stage system allows one bird to finish its meal as another enters to be weighed.

Two studies led by Zuidhof’s team highlighted different advantages of using RFID for broiler breeder producers, who are feeling the effects of declining hatchability currently occurring across North America.

“Hatchability is critical for success in the hatching-egg sector. [It] is one of the key things that drives profitability and other sustainability benefits,” Zuidhof explained to an audience at the 2025 Georgia Precision Poultry Farming Conference, hosted by the University of Georgia. “In the last year, though, hatchability has declined about 2% in Canada and about 3% in the US. In Canadian dollars, every 1% increase in fertility translates to almost $11 per rooster.”

Precision versus conventional feeding

The first study evaluated the impact of precision feeding on bodyweight, uniformity, fertility and hatchability, compared to conventional feeding. The researchers used a 12:1 male-to-female ratio for both treatments, and both males and females were on breeder-recommended weight targets.

They weighed birds on the conventional feeding approach weekly, while precision-fed birds were weighed several times a day as standard. They sent individually identified eggs to a commercial hatchery to assess fertility.

In the precision-fed group, the researchers observed improved fertility (between 3.8% and 6%) and a 4% improvement in feed efficiency. Based on these results, Zuidhof estimated that the value of precision feeding is $65 per rooster in Canadian dollars, equivalent to approximately $47 in US dollars.

The conventional treatment required the team to use spike males — replacing unsuitable males with new ones to boost fertility — something that was not needed in the precision-feeding group. Savings related to spiking alone amounted to $12 per bird in Canadian dollars (approximately $9 in US dollars).

Although the results for male birds proved to be the outstanding finding of the work, the male birds were not the only ones that benefited, he noted.

“Male uniformity correlated with fertility, absolutely. There also appeared to be a female effect, so that may be somehow related to their bodyweight or metabolic status. That’s related to the feeding regime,” Zuidhof said.

Pushing toward earlier growth, more chicks

The second study involved using precision feeding to manipulate growth models for broiler breeder females and improve performance.

The Gompertz growth model, Zuidhof explained, is generally used to explain how poultry grow over time. His team sought to tweak key points in the growth curve, aiming to increase gain in the first phase and adjust the timing of the second phase so that female birds would put on sufficient carcass fat to trigger egg laying. This is where precision feeding came in.

“We wanted to play with those coefficients and develop a shape of a broiler breeder growth curve that would produce the most chicks. We implemented it with a precision feeding system, which gives us a great degree of accuracy,” he said.

Although the team saw no significant growth impact in the first phase, they did observe an effect on the pubertal growth spurt, which in turn significantly affected carcass fat at 22 weeks. At 59 weeks, birds that were fed with a focus on the early growth point demonstrated an increase in egg production.

Male gains bring better value

For producers interested in the technology, Zuidhof stressed that the better value proposition for performance improvements is with males.

“First of all, if you precision feed males, you need to change only 10% of your feeding system, so you can save a lot of money on expensive equipment,” he said. “Also, your benefit on one male multiplies across a ratio of almost 10 to 1, females to males. When males are at the target bodyweight, there are more successful matings.”

What this means in practice, he said, is that there is a break-even point of about 2 years for males, but for broiler breeder females, it is currently around 10 years.

“The cost of technology always comes down in an exponential manner. So that is something that we anticipate will be possible in the future,” he continued.

The male-fertility benefits illustrated by Zuidhof’s team, he noted, were “scientific accidents or serendipities,” explaining that the work was initially focused on getting female birds to lay more eggs.

The system should be in use in a commercial flock of broiler breeder males within a year, he said, with funding in place.

Getting best use from precision feeders

The uniformity benefits will also lead to better outcomes in research, he added, given that the technology can efficiently collect large amounts of data. There is also flexibility to explore different feed treatments or feeding to different growth curves. The system can run several algorithms, including ad libitum feeding.

Although the potential advantages appear broad, Zuidhof stressed that a considerable amount of labor is needed in the first week when birds are introduced to the precision feeder. Additionally, while removing competition for feed is the aim, feeding is inherently a social activity.

Finally, he suggested the possibility that a bird’s ability to thrive in such a system could be heritable, with specially selected pedigree lines possible in the future.