By Xiaowen Ma, MS

Department of Animal Science

Michigan State University

East Lansing, Michigan

The US egg industry is rapidly transitioning to cage-free housing, driven by customer demand and greater awareness of laying hens’ quality of life. With this shift comes a new question: How do different aviary designs affect hens’ behavior and welfare? Although cage-free systems provide more opportunities for natural movement than conventional cages, their layouts can vary widely, and these structural differences may influence how hens live and thrive.

Why aviary design matters

There are many cage-free aviary designs on the market, differing in the number of tiers, perch and platform arrangement, ramp accessibility and litter area size. These details matter — a well-designed aviary can make it easier for hens to navigate throughout the space, while a poorly designed one might limit opportunities for movement.

To date, few studies have directly compared how design elements shape bird behavior and, in turn, welfare outcomes.

To fill this knowledge gap, we studied two commercial three-tier aviary designs that differed in litter area size, nestbox location and resource distribution. Design A had a larger litter area located on one side of the bottom tier and colony nests positioned in the upper tier. Feed was supplied on the lower and middle tiers, while water was provided on the lower and upper tiers. In comparison, Design B divided the litter into two smaller areas on both sides of the aviary system, requiring birds to move through the tiers to access the opposite side.

Despite the split, the total litter area in Design B was larger than in Design A. Nests of Design B were placed in the middle tier, with feed available on the lower and upper tiers and water on the lower and middle tiers. Structurally, Design A had a more closed design, restricting movement between the aviary system and the litter, which birds could only reach from the bottom tier. Design B, by contrast, offered a more open layout that allowed birds to fly down to the litter from any tier.

A total of 2,464 Hy-Line Brown hens were randomly assigned at 16 weeks of age to one of the aviary designs, and conditions were maintained according to management guidelines.1 We focused on two key behavioral measures: activity and play.

Activity level

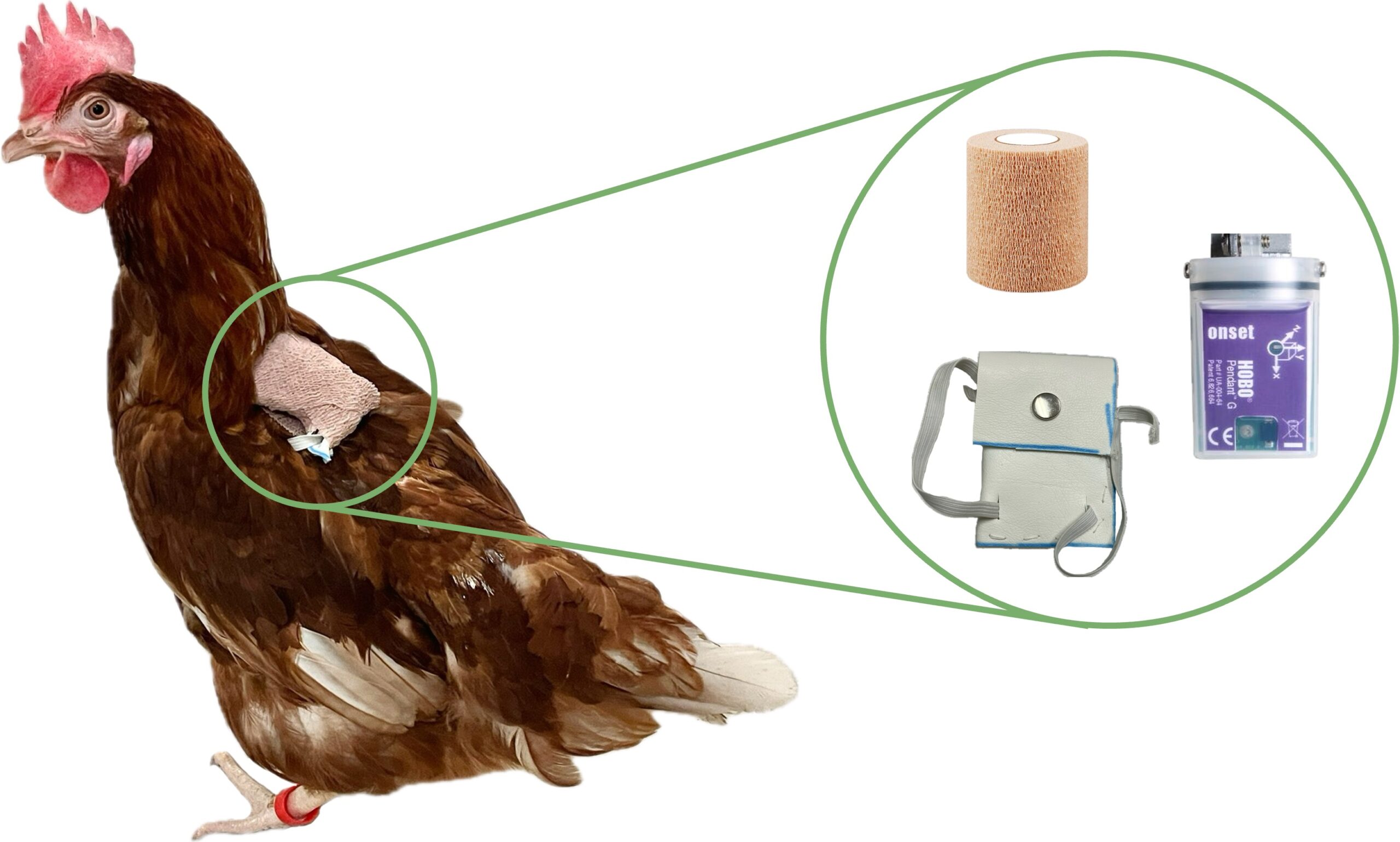

Activity levels provide insight into both physical health and behavioral needs. Animals that are injured or unwell often move less or show abnormal patterns, while healthy animals exhibit regular activity rhythms.2,3,4,5 To measure activity, we fitted hens with small accelerometers in custom backpacks to track horizontal (forward-backward) and vertical (up-down) movement (Figure 1).

We compared activity across the two aviary designs, at different stages of the laying cycle and at four timepoints across the day. This allowed us to ask: How do housing, age and time of day interact to shape daily movement patterns?

Our results showed clear and consistent patterns. In both aviary designs, horizontal activity was highest in the evening, just before the lights dimmed, and lowest in the morning, shortly after lights on. Vertical activity peaked when hens were at peak lay. Importantly, activity was not static; it changed with the birds’ age and daily schedule, as well as with the design itself.

For producers and managers, these findings suggest that housing design interacts with natural rhythms and age. Placement of ramps, perches and nestboxes can support or restrict movement, particularly at times of day or ages when hens are most active. Understanding these patterns could help refine aviary layouts to better support hen mobility and reduce competition for space.

Play behavior

Beyond activity, we also studied play behaviors such as running, wing flapping, frolicking and sparring (play fighting). Play is not essential for survival but is often considered a sign of positive welfare because it tends to occur when animals are healthy, motivated and in a relaxed state.6,7

We observed that hens engaged in play in both aviary systems, but play was expressed less often as the birds aged. By the time hens reached peak lay, most play behaviors had almost disappeared. Aviary design significantly affected only running and wing flapping, with running being more frequent in Design B and wing flapping being more frequent in Design A.

What does this mean? Play behavior may not be a reliable welfare indicator for adult hens, since it declines so sharply after lay begins. However, it could be a useful measure of positive welfare for younger birds in the pre-laying stage. The fact that play occurred at all in both aviary designs also suggests that these systems provide some opportunities for birds to express this natural behavior.

Putting it together

Looking at both activity and play provides a more complete picture of the lives of hens in cage-free systems. Activity data reveal how hens use the space and how design interacts with age and daily cycles. Play behaviors, although limited to the younger period of life, give a window into positive welfare states.

Together, these measures underscore the importance of evaluating aviary systems with age-appropriate indicators. A design that works well for young hens may not meet hens’ needs once they reach peak production. Moving forward, combining behavioral metrics like activity and play with more detailed spatial and environmental data could lead to better welfare assessments and practical improvements in system design.

References

- Hy-Line International. 2020. Hy-Line Brown Commercial Layers Management Guide: North America Edition.

- Hocking PM, Gentle MJ, Bernard R, Dunn LN. Evaluation of a protocol for determining the effectiveness of pretreatment with local analgesics for reducing experimentally induced articular pain in domestic fowl. Res Vet Sci. 1997;63(3):263-267.

- Lascelles BDX, Hansen BD, Thomson A, Pierce CC, Boland E, Smith ES. Evaluation of a digitally integrated accelerometer-based activity monitor for the measurement of activity in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2008;35(2):173-183.

- Marais M, Maloney SK, Gray DA. Sickness behaviours in ducks include anorexia but not lethargy. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;145(3-4):102-108.

- Okada H, Suzuki K, Kenji T, Itoh T. Applicability of wireless activity sensor network to avian influenza monitoring system in poultry farms. J Sens Technol. 2014.

- Duncan IJ. Behavior and behavioral needs. Poult Sci. 1998;77(12):1766-1772.

- Burghardt GM. The genesis of animal play: Testing the limits. 2005 MIT Press.