Dust particles in poultry houses can exacerbate the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), but using electrostatic precipitation and UV-C lighting can help producers reduce these risks.

In a talk at the 2025 Dust and Disease in Egg Production virtual forum, organized by the Egg Industry Center, Xuan Dung Nguyen, PhD, University of Missouri, laid out the problem with taking no mitigative action against dust at a time of high global HPAI risk.

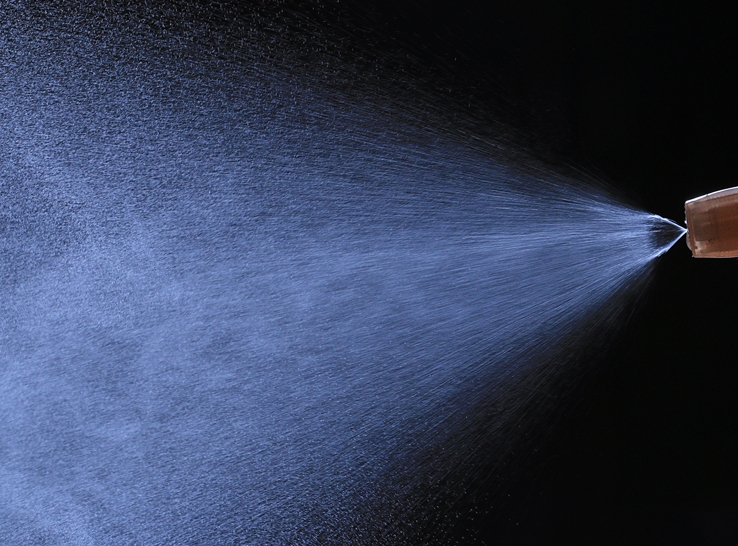

“Influenza is 10% to 50% the size of a dust particle, so the virus can very easily attach to it,” he said. “By the birds’ activity, it can easily be aerosolized into the environment and, by the ventilation system’s airflow, can be transmitted within the barn and from barn to barn.”

HPAI on dust particles can stay infectious for up to 17 hours, he noted. It can remain in the air for up to 12 hours assisted by ventilation systems and 33 minutes without this airflow. This increases the risk of transmission to humans working in production facilities, as well as the potential for more severe disease due to particles traveling deeper into the lungs.

Static, light technologies can help

Research has shown the potential benefits of two differing technologies that can be applied in poultry houses to reduce such risks, Nguyen said.

Electrostatic precipitation is a technology that uses electricity to charge particles either positively or negatively, which are then attracted to special plates and removed. “By doing so, we can reduce the dust concentration in the environment and reduce the risk of the airborne transmission of HPAI,” he told the forum audience.

UV-C light, also known as germicidal UV light, is an option to consider, he continued. It has a short wavelength and is commonly used to prevent airborne infections by damaging molecules such as DNA, thereby blocking the replication of germs like bacteria and viruses. When appropriately installed in production facilities, this type of lighting can reduce the presence of HPAI by upwards of 90%, he said.

Despite some available technological solutions, limitations persist in addressing HPAI in dusty poultry houses. He noted that real-time monitoring methods for HPAI in the production environment are still lacking, explaining that these are “very important to estimate the risk of the outbreak and also provide some further protection for the farm.”

New approaches add to understanding

Ongoing research by Nguyen’s team is examining collection methods for live, infectious viruses, which are then applied directly onto sampling media to better understand their risk to animals and humans. They are also working in the University of Missouri’s next-generation precision-farming building, in which different temperatures and humidities can be simulated to study virus-host interactions under various conditions.

“Industry collaboration is very important” for such work, he noted, pointing to his team’s work with local farming organizations, as well as with a hospital.

With HPAI outbreaks likely to cause significant losses, Nguyen stressed that improved ventilation and dust management should be at the top of farmers’ minds.

“Reducing the dust concentration means reducing the risk of the airborne transmission of HPAI,” he added.