By Vijay Durairaj, PhD*, Ryan Vander Veen, PhD* and Steven Clark, DVM**

Huvepharma

Keeping turkeys healthy is critical to ensure flock welfare, food safety and profitable turkey production. Despite the turkey industry’s best efforts, however, many diseases still present challenges for producers. Intestinal diseases are particularly costly because they interfere with the nutrient-absorption mechanism and adversely affect the health status of birds.

The parasitic disease coccidiosis remains one of the most economically significant diseases for turkeys. Not only does coccidiosis compromise gut health but it also makes turkeys more susceptible to other infectious agents. In 2023, coccidiosis ranked 10th in a US turkey industry survey of 38 health issues.

Most of the time, coccidiosis in turkeys may go unnoticed because intestinal lesions resulting from the disease are not as pronounced as in chickens. If left uncontrolled, coccidiosis can result in mortality, morbidity, poor feed conversion, low production efficiency, reduced weight gain, under-sized birds and increased costs for prophylactic measures/therapy.

Turkey coccidiosis is caused by parasites belonging to the genus Eimeria, family Eimeriidae and phylum Apicomplexa. The seven species of Eimeria that have been well-documented in turkeys are E. adenoeides, E. dispersa, E. gallopavonis, E. innocua, E. meleagridis, E. meleagrimitis and E. subrotunda. Several other species have also been isolated from turkeys but are not well-defined.

Among the seven species, four species — E. adenoeides, E. meleagrimitis, E. gallopavonis and E. dispersa — are identified as pathogenic to turkeys. Among these four species, E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis and E. meleagrimitis are considered as highly pathogenic, and E. dispersa is considered mildly pathogenic.

Eimeria replicates and invades the intestinal cells, undergoing several developmental stages resulting in extensive damage to the intestinal epithelium, which impairs intestinal digestion and absorption.

As a sequela, it disturbs the existing microbial community in the intestinal tract and destabilizes the intestinal ecology. In concurrent infections, the morbidity and mortality are often attributed to other pathogens. In such instances, the damage caused by other pathogens is overestimated, while the negative impact of Eimeria species is underestimated.

For example, if a turkey barn has an undiagnosed subclinical coccidiosis problem and the same barn is infected with histomoniasis, then the total economic losses are attributed to histomoniasis, while ignoring the subclinical coccidiosis. Thus, a comprehensive knowledge of turkey coccidiosis helps in understanding the risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and intervention strategies.

Susceptibility

While many older birds have developed immunity against coccidiosis due to earlier exposures to Eimeria and are more resistant to clinical disease, it’s important to understand that young turkeys do not acquire passive immunity against coccidiosis from the parental flocks. They are born highly susceptible to coccidiosis. In fact, regardless of age, any naïve turkey exposed to Eimeria can easily contract the disease.

Subclinical versus clinical

Subclinical coccidiosis does not exhibit any obvious clinical signs and accounts for low to moderate production losses associated with reduced weight gain and poor feed-conversion ratio.

Conversely, morbidity and mortality are clearly observed in clinical coccidiosis. Clinical coccidiosis in turkeys causes malabsorption, impaired nutrient absorption, dehydration and watery, mucoid or blood-tinged diarrhea. (It varies with Eimeria species.) This leads to dullness, depression, listlessness, unthriftiness, anorexia, huddling, a hunched or tucked-up stance, and ruffled feathers.

The morbidity and mortalities vary between farms and are dependent on Eimeria species, oocyst burden of the flock, age of the birds, nutritional status, immunity status, concurrent infections, field pressure, litter conditions and biosecurity. Poor feed quality with mycotoxins can easily aggravate coccidiosis in turkeys. The economic impact of subclinical and clinical coccidiosis is considerably high and underestimated in the turkey industry.

How is coccidiosis spread in the flock?

A turkey infected with coccidiosis sheds oocysts in the environment through fecal material. When the oocysts are shed in the feces, they are unsporulated and therefore not infective.

Sporulation occurs outside the birds in the litter. Warmth, humidity and atmospheric oxygen facilitate sporulation of the oocyst — a process that lasts 1 to 2 days depending on the Eimeria species. The minimum sporulation time for E. adenoeides, E. meleagrimitis and E. gallopavonis is 24, 18 and 15 hours, respectively.

It’s important to note that each sporulated oocyst has four sporocysts, and each sporocyst has two sporozoites. The sporozoites are the infective portion of the oocyst. When a healthy turkey ingests a sporulated oocyst, it enters the digestive tract. The mechanical action of the gizzard ruptures the oocyst wall and liberates the sporocysts.

The protease enzymes and bile salts in the duodenum cause excystation of the sporozoites from the sporocysts. Then, the sporozoites enter the intestinal mucosa and induce lesions in the intestinal tract. The infected bird sheds unsporulated oocysts in the barn and, once sporulation occurs in the litter, transmission to flock mates is possible. The oocyst burden in the flock, along with a high transmission rate, accelerates the rate of infectivity in the flock.

Interactions with other pathogens

Coccidiosis is a predisposing factor for several enteric pathogens. The lifecycle of Eimeria is complicated, and the replication occurs both intra and extracellular. As a repercussion of Eimeria replication, the intestinal cells are damaged, providing an optimum niche for other intestinal pathogens, as well as opportunistic pathogens, to invade the intestinal tract, resulting in other enteric diseases.

Any damage to the intestinal barrier could allow bacterial, viral or parasitic enteritis in the turkeys. Pathogens can easily invade the impaired gut, such as Clostridium perfringens resulting in necrotic enteritis, or Histomonas meleagridis leading to blackhead disease (histomoniasis, histomonosis) outbreaks.

Do chicken Eimeria species affect turkeys?

Eimeria are renowned for their strict host specificity. Chicken Eimeria species do not affect turkeys and vice versa. Several research labs conducted Eimeria cross-transmission studies between different hosts under normal circumstances and were unsuccessful.

E. adenoeides

E. adenoeides, one of the highly pathogenic species of turkeys, induces lesions primarily in the ceca (Figure 1). The lesions may range from petechia, congestion, edema and necrosis to sloughing of the cecal epithelium. Normal cecal contents may be replaced by abnormal cecal contents ranging from caseous clots to cecal cores.

In severe cases, the lesions may extend up to the lower small intestine and the cloaca. The minimum prepatent period is 103 hours (4.3 days). Infection causes dehydration, decreased feed intake, poor feed conversion, reduced bodyweight gain and blood-tinged diarrhea with mucous casts and mortality.

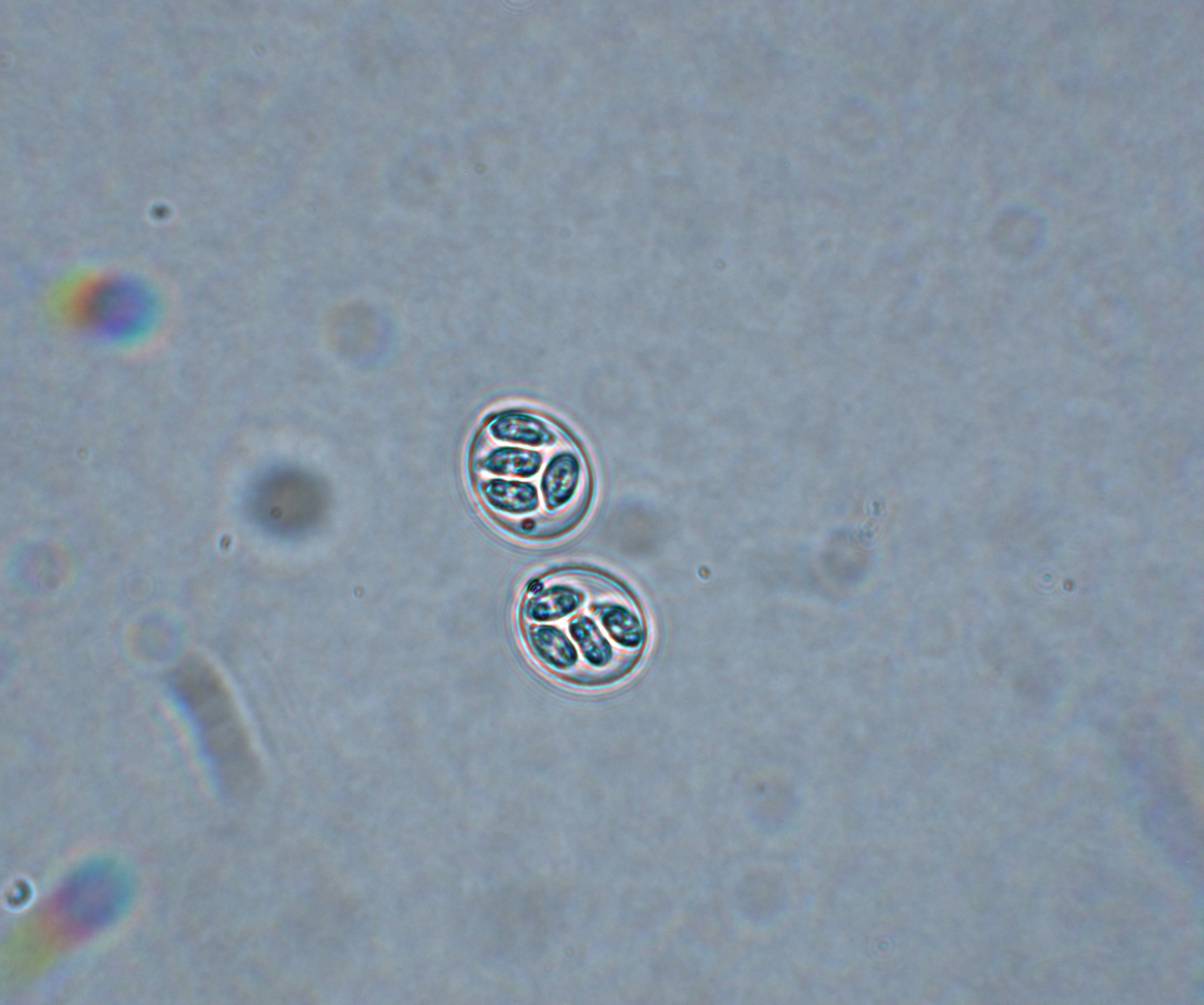

Figure 1. E. adenoeides

E. meleagrimitis

E. meleagrimitis, one of the highly pathogenic species of turkeys, induces lesions primarily in the duodenum and jejunum (Figure 2). E. meleagrimitis replicates in the intestinal cells and results in congestion and hemorrhage.

In severe cases, it results in the formation of diphtheritic membranes, sloughing and necrosis. Normal intestinal contents may be replaced with watery and mucoid contents. The minimum prepatent period is 103 hours (4.3 days). Clinical signs of dehydration, thriftiness, listlessness and diarrhea with mucus in the feces may be noticed in affected birds. Occasionally, blood-tinged feces may also be noticed.

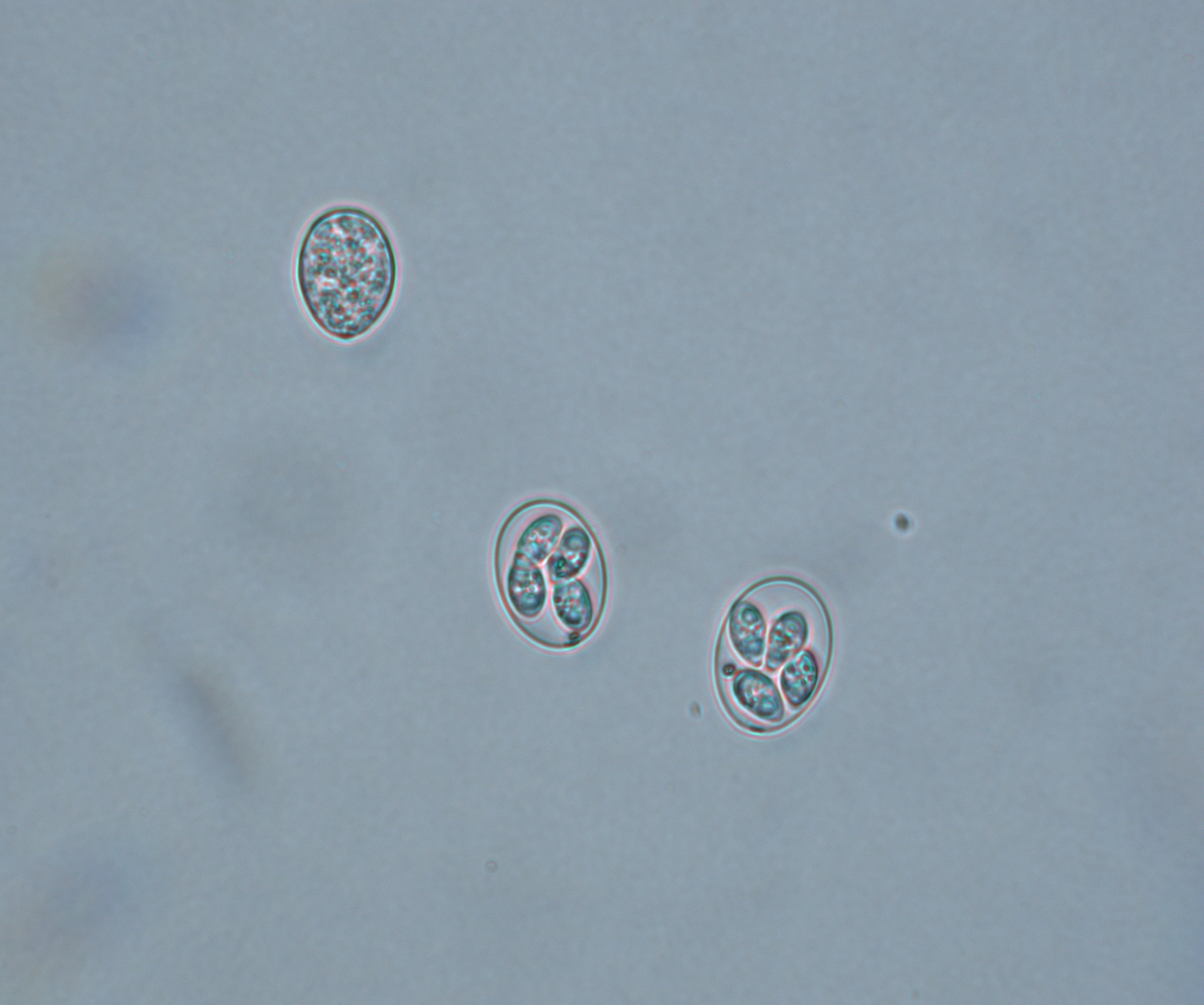

Figure 2. E. meleagrimitis

E. gallopavonis

E. gallopavonis, one of the highly pathogenic species of turkeys, induces lesions primarily in the lower small intestine, extending into the cecal neck and rectum (Figure 3). The lesions may range from white spots on the mucosa, thickened intestinal wall and hemorrhage to caseous exudate in the lower intestinal tract.

In severe cases, the lesions may extend up to midgut. The minimum prepatent period is 105 hours (4.4 days). The infection causes reduced feed intake, poor feed conversion, poor weight gain, flecks of blood in the feces and mortality.

Figure 3. E. gallopavonis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the location of gross lesions in the intestine, microscopic evaluation of mucosal scrapings and PCR.

Gross lesions

Eimeria species induce site-specific lesions in the intestinal tract. The intestinal wall should be examined and evaluated externally (serosa) and internally (mucosa) for presence of any lesions, such as petechiae and hemorrhage. The thickness, fragility and tone of the intestine needs to be evaluated. The gut contents also should be assessed for the consistency and presence of normal/abnormal contents.

In low-grade infections, lesions may recover quickly. Post-mortem investigations need to be performed during the correct timeframe to appreciate the gross lesions in the intestine. Location of the gross lesions in the intestine, along with microscopic evaluation of the morphology of oocysts, helps to identify and differentiate the species.

Microscopic evaluation

Microscopic examination of the mucosal scrapings may help to discriminate the oocysts and confirm the Eimeria species based on the morphological characteristics of the oocysts, such as size, shape and morphology, but is often complicated as the size and shape of some Eimeria species often overlap. Presence of oocysts in the microscopic evaluation reflects the presence of infection but does not indicate clinical disease.

Sometimes the oocysts of the different species might have the same size, and there might be an overlap of the oocyst size in a specific location of the intestinal tract. For example, oocysts identified in the mucosal scrapings of ceca could be either E. adenoeides (L:18.9-31.3 µm, W:12.6-20.9), E. gallopavonis (L:22.7-32.7 µm, W: 15.2-19.4 µm) or E. meleagridis (L:20.330.8 µm. W:15.4-20.6 µm).

These three species of Eimeria are ellipsoidal in shape. In mixed infections, multiple Eimeria species may be detected with an overlap in their sizes, which can complicate the diagnostic investigation. In instances where discriminating the species based on oocyst shape and size is limited, advanced molecular techniques such as PCR can help.

PCR

PCR is a valuable tool to differentiate the Eimeria species. Eimeria species-specific primers anneal to the targeted sequence and amplify it. PCR is an easy, quick and highly accurate method to differentiate Eimeria species and adds more value to the diagnostic investigation.

Differential diagnosis

Because coccidiosis often appears with other diseases, it is important to know how to differentiate infections. Following are tips for identifying Eimeria in the presence of other common diseases.

Necrotic enteritis

Diphtheritic membrane is caused by C. perfringens as well as E. meleagrimitis. In coccidiosis, the Eimeria oocysts can be identified by examination of the mucosal scrapings under the microscope.

Mycotoxins

The intestinal necrosis needs to be differentiated from trichothecenes. Mucosal scrapings help to detect Eimeria oocysts. Eimeria targets only the intestine, while trichothecenes affect the gastrointestinal tract, including oral cavity, proventriculus, gizzard, liver and intestine.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidia affects both the intestines and the respiratory system, while Eimeria affects only the intestine. Cryptosporidia can be differentiated from Eimeria based on the location in the brush border of the intestine.

Histomoniasis (blackhead disease)

Based on the formation of the cecal core, histomoniasis is a top differential diagnosis. Protozoal parasites, such as H. meleagridis, E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis and E. meleagridis, can induce the formation of cecal cores. Histomoniasis induces lesions in the ceca and liver, whereas E. adenoeides, E. gallopavonis and E. meleagridis affect only the intestinal tract and do not cause any liver lesions.

Arizonosis

Based on the formation of the cecal core, the next differential diagnosis is Salmonella enterica subspecies arizonae (S. arizonae). S. arizonae also affects the liver, resulting in a mottled and enlarged liver. Additionally, S. arizonae affects the brain, pericardium and air sacs.

Eimeria species are restricted to the intestine and can be confirmed by microscopic examination of the mucosal smear.

Why is it difficult to eradicate turkey coccidiosis?

Despite several preventive measures available for Eimeria, coccidiosis still remains a threat to the turkey industry. Eimeria species are recognized for their high reproductive potential and are ubiquitous in intense turkey-raising facilities. Eimeria multiplies at a fast rate in the intestine within a week. An infected turkey can shed millions of oocysts and transmit the disease to flock mates within a short period of time.

Because of their litter-pecking behavior, turkeys pick the sporulated oocysts from the litter, resulting in transmission of the disease. The oocysts have a tough and rigid wall that makes it resilient and protects against desiccation and commonly used chemical disinfectants. An increase in the oocyst burden results in a high level of contamination of the barns housing infected birds and can easily be carried over to the surrounding facilities.

Coccidiosis-intervention strategies

Controlling coccidiosis is a crucial component for successful turkey production. Increased incidences of coccidiosis have been reported in flocks with high bird densities. Under improper management conditions, coccidiosis can be transmitted horizontally between the turkeys in a flock.

As sporulation occurs in the litter, effective litter management is crucial. Adequate ventilation and prevention of water leaks can reduce the moisture in the litter. Increasing the downtime period and following the standards for bird density also minimize the risk of coccidiosis. Thus, good farm-management practices along with strict biosecurity measures are recommended.

Anticoccidial drugs, such as ionophores, and chemicals are administered in feed to control coccidiosis in turkeys. Proper shuttle and rotation programs can ensure adequate control with minimal risk of developing resistance.

While the terms “shuttle” and “rotation” are often used interchangeably, it’s important to understand the difference. Shuttle programs consist of changing coccidia interventions in the same flock, such as chemical anticoccidial during the brooding phase and switching to an ionophore for grow out. Changing interventions between flocks is referred to as a rotation program, such as ionophore in the summer flocks and a chemical during the winter.

Phytochemicals, which are plant-based bioactive compounds produced by plants for their protection, have also been used in control of coccidiosis and managing overall intestinal health. Having purported, either direct or indirect, to have activity against coccidia, phytochemicals may be used to supplement the current anticoccidial program.

Live vaccines are available to combat coccidiosis in turkeys. In the US, USDA conditionally licensed coccidiosis vaccine has only two species of Eimeria. Immunity against Eimeria is species-specific, meaning that if the poults are vaccinated against one particular species, then protection is offered only for that species. No cross-protection is noticed among the different Eimeria species.

Turkeys in “raised without antibiotics” or “no antibiotics ever” production schemes cannot be given ionophore anticoccidials without losing that distinction. Some production schemes also prohibit the use of FDA-approved chemical anticoccidials. For these types of operations, coccidiosis control is limited to phytogenics or vaccination.

A holistic approach with a robust gut-health program needs to be established and emphasized in turkey flocks to prevent coccidiosis. Maintaining intestinal integrity is the key to successful turkey farming. A strict gut-health program with an effective coccidiosis-control strategy is part of healthy and profitable turkey production.

For more information, please contact Steven Clark, DVM.

Publisher’s note: This article by Huvepharma originally appeared in Poultry World. The article was later updated by Huvepharma and Modern Poultry. It is posted here with permission.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.

* Huvepharma, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

** Huvepharma, Inc., Peachtree City, Georgia, USA.

References:

Cervantes HM, McDougald LR, Jenkins MC. Coccidiosis. In D.E. Swayne (Ed.), Diseases of Poultry, 14th ed., (pp. 1193-1216). Ames, (IA): Wiley-Blackwell. 2020;197.

Chapman HD. Coccidiosis in the turkey. Avian Pathol. 2008;37(3):205-23.

Clark, SR Frobel L. Current Health and Industry Issues Facing the US Turkey Industry. Proceedings 127th Annual Meeting of the USAHA, Virtual; Committee on Poultry and Other Avian Species. Pending Publication. Presented Oct 9, 2023.

Duff AF, Briggs WN, Bielke JC, McGovern KE, Trombetta M, Abdullah H, Bielke LR, Chasser KM. PCR identification and prevalence of Eimeria species in commercial turkey flocks of the Midwestern United States. Poult Sci. 2022;101(9):101995.

Gadde UD, Rathinam T, Finklin MN, Chapman HD. Pathology caused by three species of Eimeria that infect the turkey with a description of a scoring system for intestinal lesions. Avian Pathol. 2020;49(1):80-86.

Lund EE, Farr MM. Coccidiosis of the turkey. In H.E. Biester & L.H. Schwarte (Eds.), Diseases of Poultry, 5th ed., (pp. 1088-1093). Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. 1965.