By Chloe “Leo” Phelps, Virginia Tech and Leonie Jacobs, PhD, Virginia Tech

As animal welfare science has evolved, the importance of using animal-based measures to study welfare has become apparent. Birds may have needs and feelings that aren’t immediately obvious to humans, and their priorities are influenced by an evolutionary history that is vastly different than our own. Researchers must decode clues given by the birds to understand their feelings, likes, and dislikes and provide them with an environment they will most prefer.

Animal Welfare 101

The earliest conceptions of animal welfare began in the 1960s with the formulation of the five freedoms (Webster, 2016). The freedoms were the first steps in recognizing the importance of quality of life for animals.

However, as researchers have continued to learn more about animal welfare, the importance of subjective states has emerged as a way to refine how to ensure animals actually gain the benefits people provide to them (Mellor, 2017).

The five freedoms focused on preventing negative states that were easily observable by looking at an animal’s environment, such as food, water, and medical care. More recent developments in animal welfare science recognize that quality of life is, at its core, subjective and individual. In other words, quality of life is based on how the animal experiences their life from their own perspective.

The Five Freedoms

- Freedom from hunger and thirst

- Freedom from discomfort

- Freedom from pain, injury, and disease

- Freedom to express normal behavior

- Freedom from fear and distress

Emotion and quality of life

The brains of many mammals and birds have specialized systems that help them interpret their experiences, giving rise to emotions (Kret et al., 2022).

Basic emotions, including fear, distress, happiness, and enjoyment, are present in many species because they inform animals about the safety and suitability of their behavior and environment (Marino, 2017; Panksepp, 2005).

In natural environments, this ability is vital to ensure animals continue to do things that benefit their survival or reproduction and avoid things that are harmful to survival or reproduction.

When it comes to how an animal experiences their life, emotion is the lens through which they view the world (Marino, 2017). Therefore, when trying to measure quality of life, emotion is an important focus.

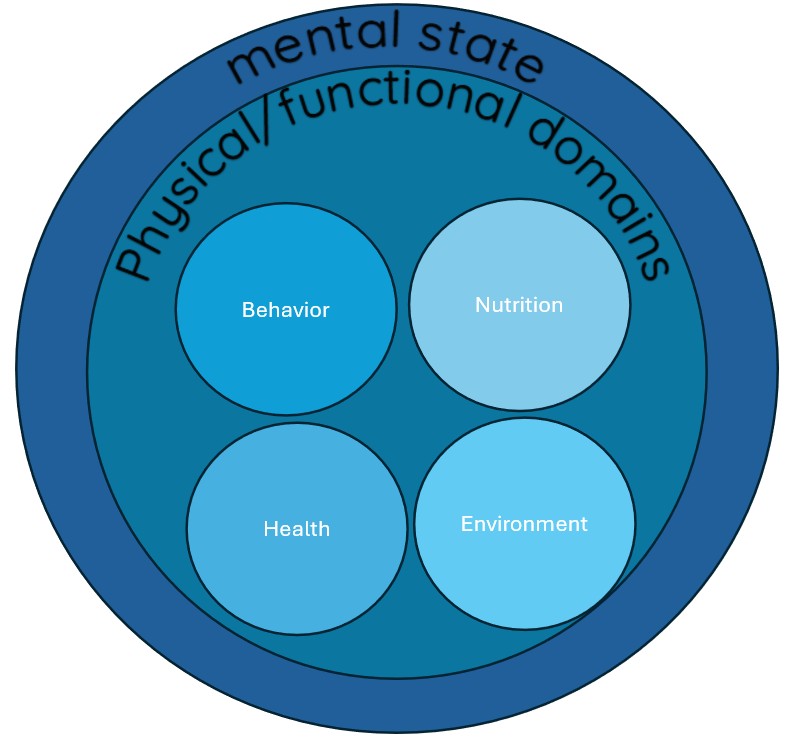

The five domains of welfare (Mellor, 2012)

Measuring emotions

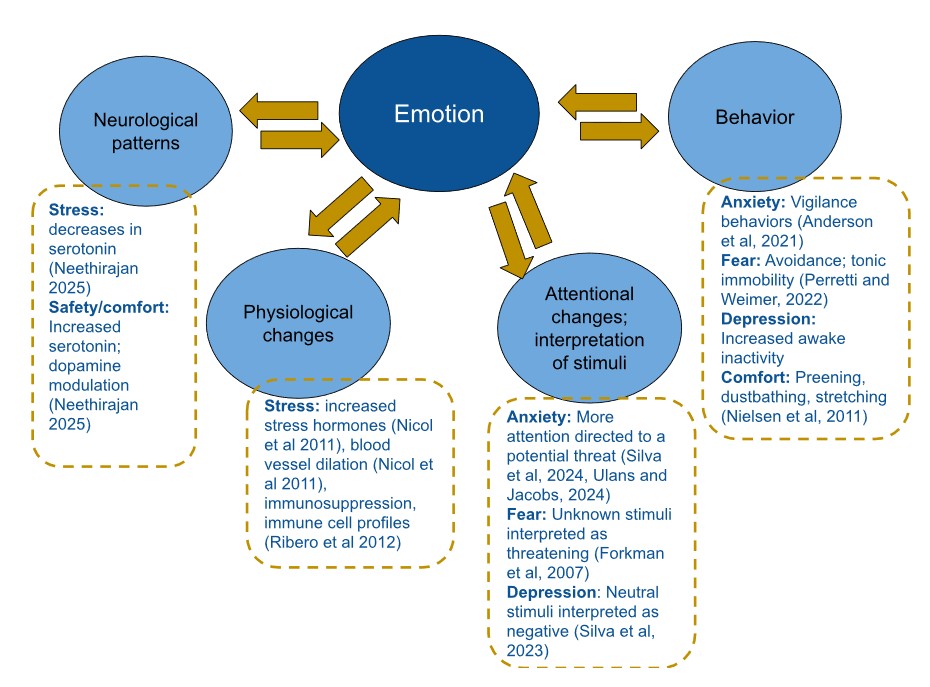

Emotions exist as a combination of neurological, psychological, and physiological responses (Manstead et al., 2004). An animal senses these biological changes (e.g., has a “feeling”) which results in changes in how it interprets its environment and how it behaves.

Emotions can be detected via investigation of any of these responses (Anderson & Adolphs, 2014). For example, during anxiety, an animal may show a physiological fight-or-flight response, a greater amount of attention directed at a threat, or particular behaviors associated with vigilance.

Elements and indicators of emotion in poultry

How does measuring emotion help us improve poultry welfare?

Poultry can show negative emotional states in environments that are overcrowded or lack enrichments and resources (Vas et al., 2023) This is important because while these environments look “unnatural” which may seem bad for welfare, it cannot be assumed that birds actually experience them this way. It was necessary to test the birds’ responses to the environment to get their perspective on it, rather than relying on a human idea of what is natural or not.

Furthermore, there is increasing recognition of the importance of providing opportunities for positive emotional states so that animals can experience a life truly worth living. Behavioral tests can help researchers understand what poultry like and want in their environments.

Measures of emotion help animal welfare scientists prevent human bias from impacting their recommendations. They can provide information about what actually matters to these birds– what motivational drives they need met to live a good life, and what interventions provide benefits they actually value.

Summary: Measuring emotions in poultry

- Many animal species, including poultry, experience emotions

- Emotions indicate the environmental suitability and safety; they also motivate avoidance of harm and approach to beneficial situations

- Assessing emotions can show us what actually matters to the animal, giving us an opportunity to improve their quality of life

- Through measuring behavior and physiological changes, researchers can get a “birds eye” view of how welfare interventions actually improve the lives of poultry.

References and further reading

- Anderson, D. J., & Adolphs, R. (2014). A Framework for Studying Emotions across Species. Cell, 157(1), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003

- Anderson, M. G., Campbell, A. M., Crump, A., Arnott, G., Newberry, R. C., & Jacobs, L. (2021). Effect of Environmental Complexity and Stocking Density on Fear and Anxiety in Broiler Chickens. Animals, 11(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082383

- Forkman, B., Boissy, A., Meunier-Salaün, M.-C., Canali, E., & Jones, R. B. (2007). A critical review of fear tests used on cattle, pigs, sheep, poultry and horses. Physiology & Behavior, 92(3), 340–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.016

- Kret, M. E., Massen, J. J. M., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2022). My Fear Is Not, and Never Will Be, Your Fear: On Emotions and Feelings in Animals. Affective Science, 3(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-021-00099-x

- Lourenço-Silva, M. I., Ulans, A., Campbell, A. M., Almeida Paz, I. C. L., & Jacobs, L. (2023). Social-pair judgment bias testing in slow-growing broiler chickens raised in low- or high-complexity environments. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 9393. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36275-1

- Manstead, A. S. R., Frijda, N., & Fischer, A. (2004). Feelings and Emotions: The Amsterdam Symposium. Cambridge University Press.

- Marino, L. (2017). Thinking chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Animal Cognition, 20(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-016-1064-4

- Mellor, D. J. (2017). Operational Details of the Five Domains Model and Its Key Applications to the Assessment and Management of Animal Welfare. Animals, 7(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7080060

- Neethirajan, S. (2025). Rethinking Poultry Welfare—Integrating Behavioral Science and Digital Innovations for Enhanced Animal Well-Being. Poultry, 4(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4020020

- Nicol, C. J., Caplen, G., Edgar, J., Richards, G., & Browne, W. J. (2011). Relationships between multiple welfare indicators measured in individual chickens across different time periods and environments. Animal Welfare, 20(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600002621

- Nicol, C. J., Caplen, G., Statham, P., & Browne, W. J. (2011). Decisions about foraging and risk trade-offs in chickens are associated with individual somatic response profiles. Animal Behaviour, 82(2), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.04.022

- Nielsen, B. L., Thodberg, K., Malmkvist, J., & Steenfeldt, S. (2011). Proportion of insoluble fibre in the diet affects behaviour and hunger in broiler breeders growing at similar rates. Animal, 5(8), 1247–1258. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731111000218

- Panksepp, J. (2005). Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans. Consciousness and Cognition, 14(1), 30–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.004

- Perretti, A., & Weimer, S. (2022) Fear Tests in Poultry. Poultry Extension Collaboration Newsletter, 33. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zXGJKEEQN6jUNxMidPnoD4GREylkZuqE/view

- Ribeiro, L. R. R., Sans, E. C. de O., Santos, R. M., Taconelli, C. A., de Farias, R., & Molento, C. F. M. (2024). Will the white blood cells tell? A potential novel tool to assess broiler chicken welfare. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1384802

- Silva, M. I. L. da, Ulans, A., & Jacobs, L. (2024). Pharmacological validation of an attention bias test for conventional broiler chickens. PLOS ONE, 19(4), e0297715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297715

- The Five Freedoms: A history lesson in animal care and welfare. (2019, September 6). 4-H Animal Science. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/an_animal_welfare_history_lesson_on_the_five_freedoms

- Ulans, A., & Jacobs, L. (2024) Walking on eggshells– assessing anxiety in chickens. Poultry Extension Collaborative, 52. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bSgHi9dL95xQtFVi_8_ST6UJFDVE7Wd5/view

- Vas, J., BenSassi, N., Vasdal, G., & Newberry, R. C. (2023). Better welfare for broiler chickens given more types of environmental enrichments and more space to enjoy them. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 261, 105901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2023.105901

- Webster, J. (2016). Animal Welfare: Freedoms, Dominions and “A Life Worth Living.” Animals, 6(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani6060035

To view all issues of Poultry Press, click here.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.