Controlling foodborne pathogens in poultry requires nearly identical approaches whether production is conventional or antibiotic-free, according to Chuck Hofacre, DVM, PhD, president of the Southern Poultry Research Group, Inc.

Just under 80% of US poultry production is either no-antibiotics-ever or uses only ionophores to control coccidiosis, he told an audience at the 2024 Emerald Coast Veterinary Conference in Florida.

Coccidiosis control is intrinsically linked to bacteria associated with food safety, with known connections between coccidiosis-control programs and the amount of Salmonella seen on farms, Hofacre said.

Good gut health is at the heart of controlling multiple common pathogens across the different modes of poultry production. Measures that help ensure birds have healthy gut flora are often the same as those that effectively manage both coccidiosis and Salmonella.

Links between coccidia control, gut health

He pointed to a necrotic enteritis challenge study by his team, in which broilers were placed on reused or fresh litter and treated with a fatty acid product. Half the birds were then directly challenged with Salmonella Enteritidis and half horizontally challenged by contact with the infected birds.

His team found that the birds on the new litter had greater mortality and higher levels of Salmonella positives in their ceca.

“The reused litter probably had a lot of normal flora or good bacteria besides the Clostridium that was in there from the previous flock. Those baby chicks were exposed to that normal flora immediately when they were placed,” he said.

“In my clinical experience in working with production companies, we often see healthier flocks on reused litter than we do on new litter, which confirms that we’re probably seeing a probiotic effect of the reused litter.”

Further work has shown that when birds are infected with coccidiosis, it affects intestinal flora and bird immune responses, he continued, adding that subclinical coccidiosis exposure similar to the level seen in coccidiosis vaccination has been linked with increased resistance to Salmonella in broilers.

“In my opinion, foodborne-pathogen control in a conventional and an antibiotic-free production system is going to be almost the same. How we control coccidia isn’t as important as the fact that we are controlling coccidia,” Hofacre commented.

Breeder focus

Coming to terms with foodborne pathogens requires renewed focus on broiler breeders, he suggested, pointing to a study that traced circulating types of Salmonella Kentucky across thousands of broiler samples back to grandparent stock.

“From my perspective, 80% of the Salmonella that we see on our broiler farms originates in our broiler breeders. It comes down through either eggshell contamination or true transovarial transmission into our hatchery, and then that disseminates it to our broilers,” he said.

To tackle foodborne pathogens at the source, intestinal health should be a critical focus of efforts, specifically reducing intestinal epithelium damage that is often caused by coccidiosis.

“I think if we can keep the intestines healthy, the bacterial flora will help us maintain broiler health and performance on one side and lower our Salmonella and potentially the Campylobacter burden on the other,” Hofacre continued.

Combining vaccines and additives

Although there is no “silver bullet” to ensure either gut health or Salmonella control, he said, combinations of multiple measures, including dietary supplements and vaccination, can bring significant improvements in both, whether in an antibiotic-free or conventional program.

“A lot of the things that we do to maintain good gut health may also help us with Salmonella control. It’s not one or the other. I think what we have to look at is where we can join the two together,” he said.

Live vaccines have been “a very consistent means for us to reduce Salmonella”. In a study with pen studies by Hofacre’s team where half of birds were challenged with S. Heidelberg, 90% of those in control pens were Salmonella positive, with no positives among those treated with a live S. Typhimurium vaccine.

Although vaccination can be effective against S. Heidelberg and help with S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis, it doesn’t have the same impact against serogroup C Salmonella, like S. Kentucky. Combining vaccination with other measures can help, he said.

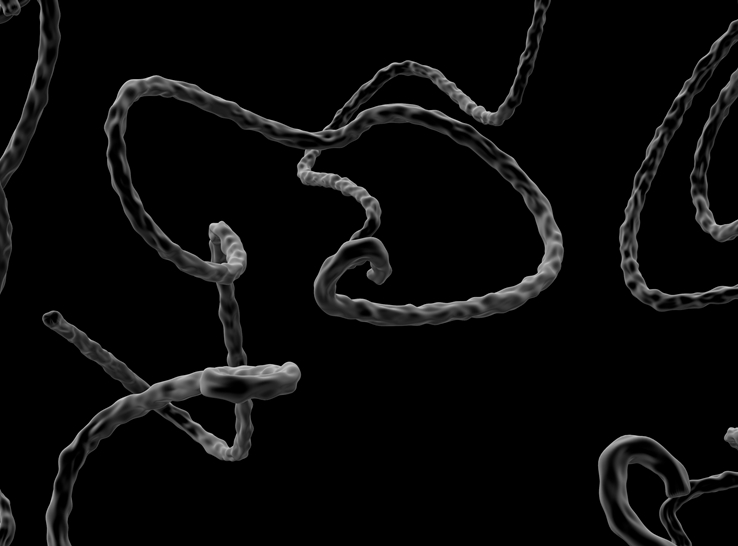

He highlighted research showing the efficacy of novel feed additives such as yeast, yeast cell walls, probiotics and organic acids, also noting the breakthrough potential of bacteriophages, which are beginning to become commercially available.

He also mentioned that some dietary supplements can increase the effectiveness of vaccination programs by stimulating a stronger immune response.

New products are likely to be available soon “that may blur the lines between vaccines and probiotics,” he said, while other vaccines will be targeted at covering multiple serovars more effectively. New adjuvants are also around the corner that will open the opportunity to use inactivated vaccines in broilers.

Regardless of the technology, Hofacre still believes that producers will need to use multiple interventions as part of Salmonella control programs.

Tackling ubiquitous Campylobacter challenge

Campylobacter may be a tougher nut to crack, Hofacre acknowledged. It is the No. 1 cause of bacterial foodborne illness in the US, and its prevalence tends to be very high in broiler production facilities.

The issue is less about managing the situation with broiler breeders, as horizontal transmission is the primary concern.

“When it comes to Campy, we’ve got a bigger struggle on the farm. We’ve got to find a way to reduce the numbers so that it’s not such an overwhelming load coming into our processing plants,” he explained.

He noted that while many of the same interventions that work for Salmonella may also work for Campylobacter, producers are “going to have to get creative” to keep the latter at acceptable levels more effectively, noting a study in which researchers used all the recommended interventions from a panel of experts on a farm delayed when the farm went Campy positive.

One key finding of the work was that positive flocks were recorded soon after the darkling beetle population spiked in houses. If the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service begins regulating for Campylobacter in processing plants, Hofacre believes this is where efforts should be placed.

“We’re really going to need to focus on our beetle control, because I think that’s where part of our exposure and the source of our Campy is. The beetles may also help maintain high levels of other pathogens on our broiler farms,” he added.

Ultimately, maintaining good bird health and uniform performance while keeping foodborne pathogens low is no simple task, especially in the face of higher regulatory demands.

“We’re going to need to spend more time on interventions on the broiler farms. Maintaining good gut health is going to be part of our Salmonella and Campy control on our broiler farms so that we end up with carcass rinses that have less of both,” he added.