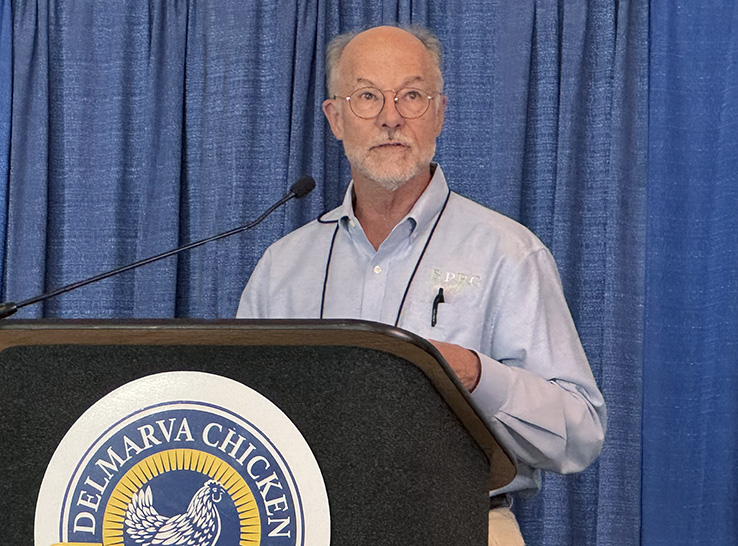

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) plans to pay closer attention to the level of Salmonella coming from broiler farms — but “it’s not that complicated” to get things right, according to Chuck Hofacre, DVM, PhD, president of the Southern Poultry Research Group, Inc.

Although responsibility for minimizing Salmonella risk to the consumer previously fell largely on processing plants, times are changing. Fortunately, best practices already carried out by producers to reduce the prevalence of ubiquitous diseases are the route to success under the new FSIS approach, Hofacre told an audience at the Delmarva Chicken Association’s 59th National Meeting on Poultry Health, Processing and Live Production.

“The things that you do basically every day are going to have an impact for us on reducing Salmonella coming into the plant from our farms,” he said.

Success in the water

Water line sanitation is one of the main ways to reduce Salmonella among broilers, Hofacre explained.

“The importance of water line sanitation goes beyond bird health and performance. It could impact whether a company has to destroy a flock because they’ve got a certain Salmonella,” he said. “Salmonella loves to live in that biofilm. ”

Avoiding wet litter is another key management aspect that keeps Salmonella down, he noted.

Names change, control doesn’t

In keeping farms below the likely new FSIS threshold, not all Salmonella are the same, he stressed. For example, the Kentucky serovar colonizes very successfully but poses a lower risk of foodborne illness. Other serovars, such as S. Heidelberg, have caused illness outbreaks in the past, while S. Infantis is a current serovar in the spotlight.

“Tomorrow there’ll be another one, so don’t get surprised if the names change. But a lot of the things you do to control one Salmonella are going to be very effective in controlling others,” he said, noting that whether a company uses a traditional program or no-antibiotics-ever system is unlikely to make much difference in control.

Getting the basics right is what matters.

“Live vaccines are a big tool in our arsenal,” Hofacre continued. He pointed to work carried out by his team at an FSIS category 2 broiler producer that was at risk of becoming a category 3. Category 2 premises meet the maximum allowable percentage of Salmonella-positive tests but are over 50% of the allowance in the most recent 52-week window, while category 3 farms exceed the maximum allowance in the most recent window.

His team vaccinated at day of age using spray application and in the drinking water. After sampling ceca near processing, it initially looked like there was no difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

However, further analysis showed that vaccination had been effective in decreasing the prevalence of Salmonella group D, which includes S. Enteritidis, a leading cause of foodborne illness. Vaccination didn’t have much of an effect on S. Kentucky, but that “is not as big a concern,” he said.

Necrotic enteritis connections

Controlling coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis are primary worries for producers, and proven links between the causes of these problems and those of Salmonella mean that control measures put in place for one may impact the other, Hofacre said.

Probiotics are widely used to competitively exclude pathogens, particularly in antibiotic-free systems at the times when birds are at most risk of necrotic enteritis, he continued. Using direct-fed microbial products such as Bacillus in either drinking water or feed can also help reduce Salmonella in poultry houses.

“Remember that gut flora is important not just for Salmonella control, not just for gut health for necrotic enteritis, but also if the intestines are healthy, birds pass less wet droppings so there is less wet litter and improved footpad quality,” he stressed.

Tools for frontline fight

Multiple measures are better than any individual one, Hofacre continued, pointing to research showing that, although an organic acid in the water and competitive exclusion both have an effect in isolation, combining the two produces a significantly lowered Salmonella risk.

Fieldwork has also demonstrated the benefits of organic acids, used continuously in feed or drinking water during the withdrawal period, for reducing Salmonella, he said. In one study with a producer that was at risk of losing its line speed waiver, using a new product containing an organic acid and essential oil had a positive impact.

This impact was more pronounced when used for the 72 hours before the birds went to the plant, as opposed to 48 hours, with the longer treatment resulting in nearly a 50% decrease in Salmonella.

“If some of the new FSIS regulations being proposed come to pass, it may change some of the things you do on the farm, but it’s not going to change a lot,” Hofacre concluded. “It’s just going to mean we’re going to have to pay a little closer attention to the details and to the things that really count, for example, like water line sanitation or making sure that we are running a probiotic in the drinking water.”

It’s imperative that service technicians understand what is likely to have the biggest impact in their houses, he added, as “you are going to be on the frontlines of the farm control, just like the processing plant is on the frontlines in the plant for Salmonella control.”