By Matthew J. Hardy, MSc

AgriNerds – Co-owner, Waterfowl Biologist and Co-director of Ecological Modeling

Chester County, Pennsylvania

(Part 1 of 4, Waterfowl migration and HPAI risk across North America)

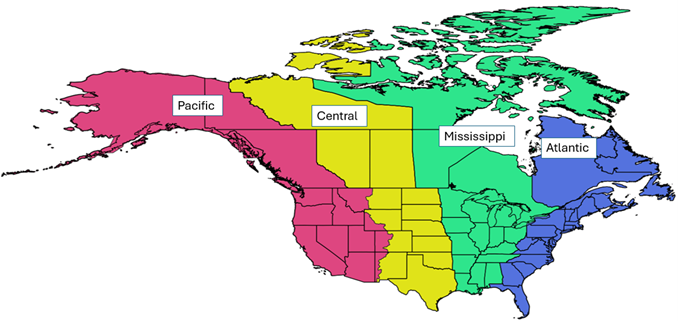

Each year, as millions of waterfowl soar across North America’s skies, they follow ancient migratory routes that span thousands of miles across all four major flyways: Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic.

Among the most important of these travelers are the dabbling ducks, including species like the Mallard, Northern Pintail, American Wigeon and Blue-winged Teal. These shallow-water foragers are more than just an iconic part of America’s seasonal wetlands; they are central to understanding and managing the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) across the US.

Dabbling ducks: why they matter

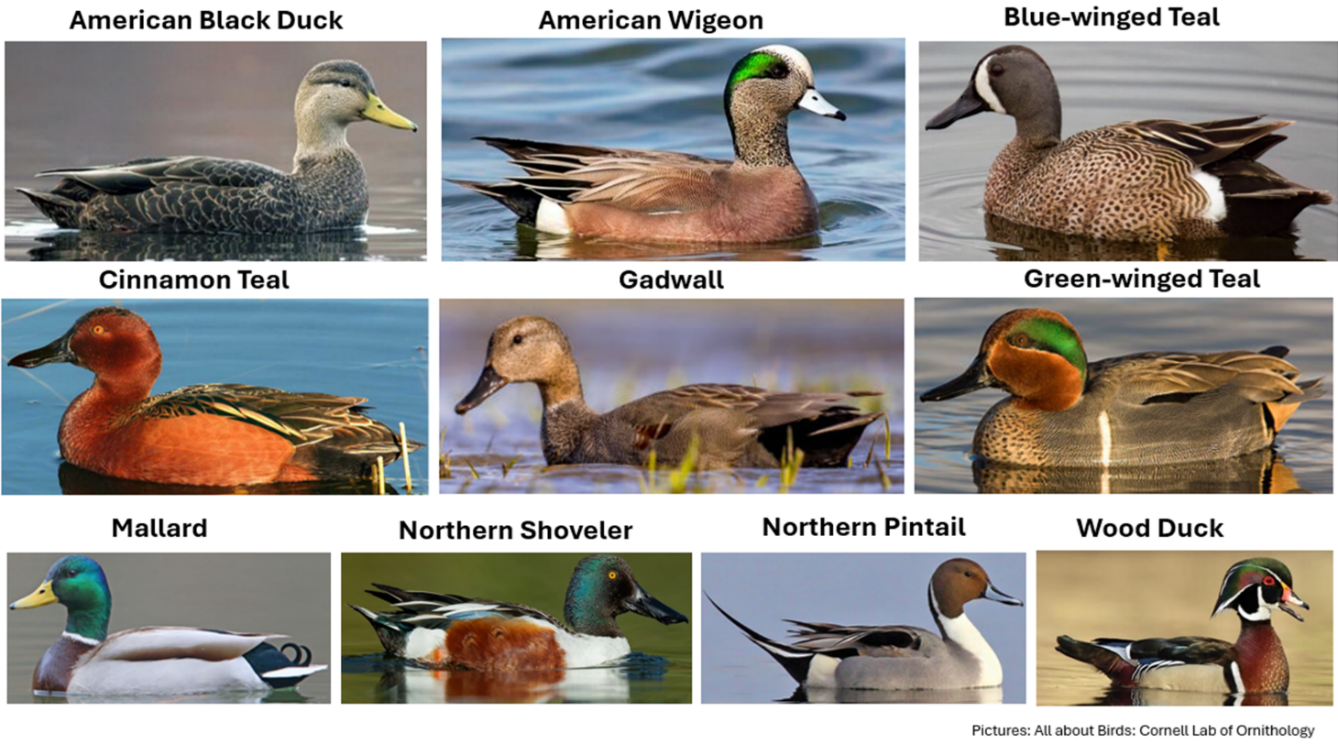

Dabbling ducks forage in shallow wetlands, where their high densities, feeding style and migratory patterns make them compatible reservoirs for HPAI. Dabbling ducks are a group of waterfowl that feed by tipping forward in shallow water to forage on the surface or just below it, rather than diving (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Species of dabbling ducks

They often forage in flooded agricultural fields and use waterbodies and wetlands in and around poultry and dairy facilities, increasing the chances of spreading HPAI between wild birds and domestic animals. Consequently, their timing and movement patterns significantly influence the seasonal surge of HPAI, particularly during spring and fall migrations.

Dabbling ducks use a filter-feeding mechanism that involves using specialized combs in their mouth called lamellae, which allow them to strain water, sediment and vegetation or invertebrates for food. However, this feeding mechanism increases their exposure to ingesting pathogens like HPAI.

Additionally, constant interactions with many other species sharing contaminated water sources make dabbling ducks one of the most important natural reservoirs and vectors of HPAI, as they can carry and spread the virus without showing clinical signs.

Varying annual HPAI incidence

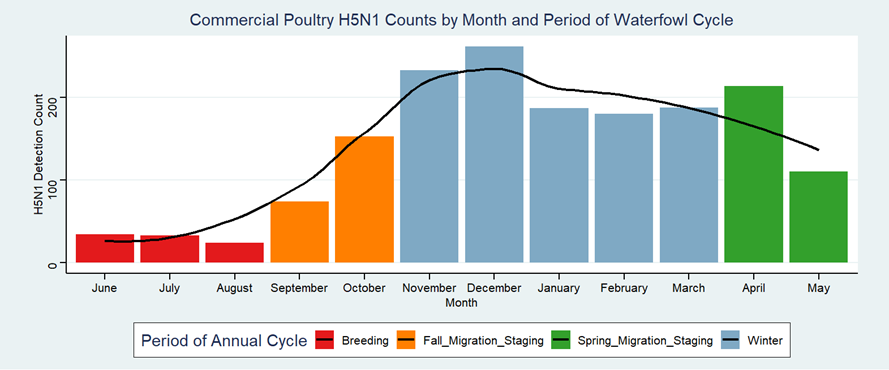

Most migratory waterfowl in the US are on northern breeding grounds during summer (June to August), reducing contact with US poultry. Cases rise from April to May as birds move north, and peak again from October to April during southward migration and overwintering (Figure 2).

Even during the summer, resident (non-migratory) dabbling ducks may sustain the virus in the environment, providing a bridge between peak seasons. Young waterfowl in the fall are more susceptible to the virus due to their naïve immune systems. Understanding their behavior and flight paths can help wildlife managers and poultry producers anticipate and mitigate outbreaks.

Figure 2. Annual cycle of H5N1 detection counts

Flyway patterns, high-risk zones

Dabbling ducks follow different routes and use various habitats depending on species and geography during their annual cycles. However, they all contribute to a shared continental picture of HPAI risk. By understanding how HPAI risk varies by flyway, species and time of the year, farmers can anticipate periods of higher threat based on migration patterns and implement targeted biosecurity measures to protect their operations (Figure 3).

Here, I break down the general trends by flyway:

Pacific flyway

In spring, ducks travel north through California’s Central Valley, the Klamath Basin and the Pacific Northwest. By summer, they settle into breeding grounds in Alaska, British Columbia and the Yukon. As fall sets in, high densities of dabblers congregate in flooded rice and wetlands in the Sacramento Valley, the Great Salt Lake and the Columbia Basin, leading to elevated HPAI risk in these regions. Wintering birds continue to pose threats in California, Washington and Nevada.

Central flyway

Spring migration brings flocks to staging areas like Nebraska’s Rainwater Basin and Kansas’s Cheyenne Bottoms. Breeding occurs in the Prairie Pothole Region, also known as “The Duck Factory,” which spans North Dakota, South Dakota, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In this region, water conditions vary from year to year.

In the fall, flocks concentrate in Texas playas and Oklahoma wetlands, with winter movement extending into Texas, New Mexico and northeastern Mexico (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Flyway patterns

Mississippi flyway

This corridor sees heavy spring traffic along the Illinois River, Mississippi Delta and the Ohio River Valley. Ducks breed in the Upper Midwest — Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan — and central Canada. During the fall, HPAI hotspots include the Arkansas Grand Prairie and Louisiana’s rice-growing regions. Winter brings dense flocks to the lower Mississippi Valley, Louisiana coast and Texas Gulf region, all close to major poultry operations.

Atlantic flyway

Spring migrants use the Chesapeake Bay, New Jersey and New York wetlands as stopovers. Summer breeding occurs across the Canadian Maritimes, boreal Quebec and the northeastern US. Fall risk peaks in the Delaware Bay, the Carolinas, New England and southern Ontario and Quebec. In winter, the risk overlaps significantly with poultry production, as ducks feed in agricultural areas, wetlands and other waterbodies along the Atlantic coast, including the Chesapeake region, the Carolinas and Florida.

Figure 4. Real-time tracking

Forecasting movement in real time

To better prepare for and respond to HPAI threats, technology is stepping in. The WaterFowl Alert Network, developed by AgriNerds, provides real-time forecasts of waterfowl movement across the US. This tool gives poultry farmers, conservationists and wildlife managers timely insights to make location-specific decisions about biosecurity and habitat management (Figure 4).

By integrating next-generation weather radar, GPS tracking and environmental data, this system helps stakeholders anticipate when and where risk will spike, providing a vital edge in the ongoing effort to balance wildlife health with agricultural safety.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.