Utilizing technology to monitor the efficacy of immunization strategies is key to keeping infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) as “background noise” this winter, according to a diagnostics expert.

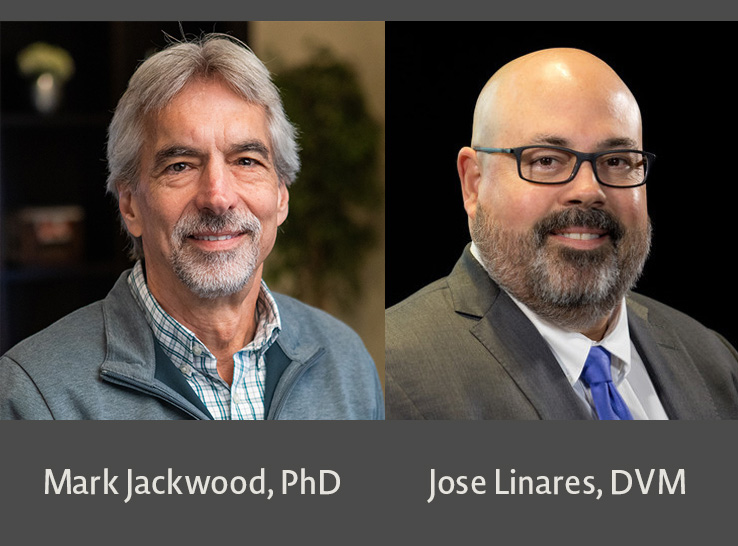

Jose Linares, DVM, a diagnostician and technical services veterinarian at Ceva Animal Health, said pre-winter surveillance – including reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) testing, sequencing and processing-age serology – can help veterinarians and producers validate current IBV immunization strategies and ensure they are relevant and effective.

This is critical before cold weather, when potential ventilation issues and ammonia buildup could worsen respiratory challenges. Optimal IBV immunization helps prevent increased condemnations, processing line slowdowns and increased reprocessing costs.

Routine vaccination-take checks in the first week of broilers’ lives – carried out via swabbing and RT-qPCR around 5 to 7 days after hatchery vaccination – help validate optimal vaccine delivery, which is the foundation for IBV immunization. Ceva has run this check since 2015 and routinely sees good takes with Mass +IBRON at the hatchery, Linares said.

However, vaccine detection is the audit, not the headline, he explained.

“Vaccination is the act. Immunization is the outcome,” he said during a presentation at the 15th International Seminar on Poultry Pathology and Production in Athens, Georgia, explaining that the goal is to prove the outcome before winter pressure hits.

Ahead of winter, respiratory surveillance via RT-qPCR shows what’s circulating – a broad 5′UTR ‘hunting’ PCR to flag IBV, type-specific assays to identify strains and next-generation sequencing when patterns don’t fit. This step separates the vaccine from the field strains and confirms if a new variant has arrived.

However, he stressed that the PCR test is very sensitive and that results must be interpreted alongside flock health and performance. “With PCR, if you look, you will find,” he said. “The question is whether what you find is having a negative impact on the birds.”

That distinction mattered last winter, when several complexes became concerned after routine PCR screening picked up Newcastle virus (NDV). However, NDV sequencing showed they were non-virulent strains with little consequence for birds, compared to the negative impact of Avian Metapneumovirus in combination with bacterial infections.

Matching protection to the challenge

In the US, field challenges in recent years have been dominated by DMV1639. Complexes that kept using older vaccines and vaccine combinations, such as Mass, Mass/Conn, Mass/Ark or Ga98/Ark, walked into DMV without cross-protection, Linares said. High virus loads were detected in the trachea, air sacs and kidneys, which translated into losses in feed conversion average daily gain and at the processing plant.

When programs switched to DMV1639-relevant cross-protection, such as Mass + IBRON, and vaccine take was proven, winter ‘blips’ surfaced on surveillance charts, but widespread outbreaks didn’t follow.

“The key is to match the vaccine to the challenge and apply it properly,” he explained. “If you do that, broilers won’t need field boosters. Just the hatchery dose done right is enough.”

Measuring antibody levels through serology gives producers another way to listen to birds, albeit over a longer timeframe, Linares said.

In one northeast Georgia small-bird program (38 to 42 days), processing-age IBV mean titers averaged about 1,050 to 1,170 in both 2019 and 2020, even as DMV/1639 moved through the area.

That stability, plus plant performance, showed the vaccination program that the unit had implemented was holding the line – especially when statewide benchmarking mean titers climbed to 2,500 to 3,000 at processing age as naïve flocks were hit.

“If titers stay steady while the area gets hit, you’ve built protection. If they spike, you’ve got a problem to investigate, but an antibody spike by itself can also mean protected birds were challenged, and the immune system responded and helped clear the infection with minimal to no consequences.”

Avoiding false alarms

Linares said people often think increased testing is a sign of lab work creeping into everyday management, but, in reality, it’s the opposite.

“The tools help you make fewer assumptions and act when the birds and the data both say you should. RT-qPCR can find both vaccine and field viruses, so when strain-specific assays blur – because viruses mutate in the small stretch the test targets – next-generation sequencing clears up which strain is present and whether it’s a vaccine or a field isolate.”

This is useful not just to avoid false alarms, but also to document what Linares calls the “vaccine exchange” seen in high-density broiler production areas, where tunnel ventilation can carry vaccine virus from one farm to the next.

“You’re ventilating your vaccine out of the houses – it goes with the wind,” he said. “Finding a neighbor’s vaccine by PCR is expected in dense areas; the question is whether it’s doing anything to your birds.

“You’ll detect your program, the local challenge virus and your neighbor’s vaccines all in the same dataset. The birds ‘tell us’ which one matters.”

Creating the best environment

Litter and air quality also affect outcomes. Last winter, Linares said he saw the same issue repeatedly, where three houses would be fine, but the fourth would have noticeably higher ammonia levels.

Rather than being the result of one dramatic mistake, he said the issue would mostly arise from several smaller problems, such as a weak fan, a mis-set louvre or a leaky waterline, which create wet litter that breeds bacteria and produces ammonia.

“In these instances, it’s important to burn off ammonia before placement,” Linares said. “Close up and heat the house so bacteria in built-up litter release ammonia, then ventilate hard before the chicks arrive.

“We ventilate less after placement to keep chicks warm, then the ammonia peaks with birds on the floor — exactly when they don’t need it,” he added.

Managing IBV spread

Modeling shows that IBV spreads quickly in naïve flocks (around 20 secondary cases per case) and struggles in protected ones (below 1:1 spread), which explains why hatchery vaccination is vital and delivery must be uniform.

In practice, Linares said producers should focus on three things before winter:

- Verify vaccine take at day 5 to 7.

- Read any lab hits against how birds and processing plants are performing.

- Ventilate for moisture while burning off ammonia before placement, so you’re not cooking it out with chicks on the floor.

Taking this approach means IBV will remain as ‘background noise’ rather than a reason to slow a processing plant line.

“Only the chickens can ‘tell’ us what diagnostic findings mean, so it’s critical to go to the farm and examine the birds,” he added.

For broiler companies that take that literally, the cold months look far less risky, and the savings show up financially, not just in lab results.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.