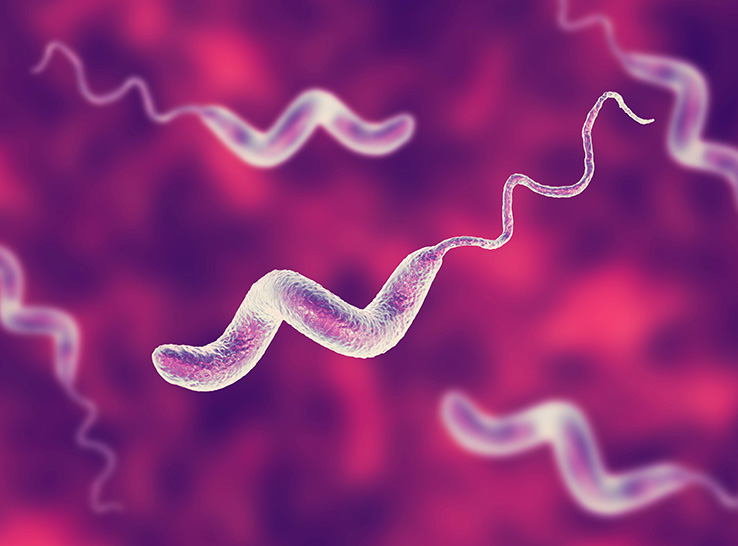

On-farm research reveals a tough road ahead for broiler farms trying to reduce levels of Campylobacter jejuni, the major cause of bacterial foodborne illness in humans in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

“What we understand about Campylobacter is very small compared to what we understand about Salmonella,” reported Chuck Hofacre, DVM, PhD, president of Southern Poultry Research Group. “These are two very distinct organisms, and they behave very differently within chickens.”

In a webinar organized by the Poultry Science Association, Hofacre discussed how difficult it is to reduce Campylobacter levels on farms compared to Salmonella.

He presented information learned from research projects including a USDA-funded study in 2008-2009 that followed 55 broiler flocks from the farm through processing. The flocks were tested on the farm a week before processing and then four sample locations during processing for both bacteria. To prevent cross contamination, the research flocks were first to come into the processing plant in the morning.

Results of the study revealed some surprising differences between Campylobacter and Salmonella levels in broilers.

High Campylobacter loads

“Campylobacter is on the farm in much higher numbers than we see for Salmonella,” Hofacre said. They discovered this while trying different sampling methods, including boot sock, drag swab, fecal sample and litter sample.

“For Campylobacter, it didn’t matter what sample method we used, we were going to find it,” he said. “So, the technique to sample Campylobacter isn’t as important as it is with Salmonella. However, boot socks are good to sample for both.”

They also learned that if one bird in the flock was positive for Campylobacter, most likely all were positive. As a result, the Campylobacter infection level was much higher than Salmonella when the birds entered the processing plant, he noted.

In addition, Campylobacter wasn’t detected in broilers until 7 to 14 days of age while Salmonella could be detected as young as day 1. “Experts have not sorted out the reason for Campylobacter not appearing and then suddenly showing up,” Hofacre added.

Resists processing interventions

Campylobacter levels remained high throughout processing in the USDA study. Levels started at 68% outside the plant and dropped only to 43% by post-chill. Salmonella levels dropped significantly from 46% outside the plant to just 2% at post-chill.

“Processing interventions don’t appear to be reducing or eliminating Campylobacter as effectively as they are with Salmonella,” Hofacre said. “The reason why is the numbers. For Salmonella, the means start around 1 log, and as broilers move to post-kill rinse, the numbers were nearly zero.

“But for Campylobacter, we start with a mean of almost 5 logs and interventions drop it from 5 to 4 logs and 3 to 2 logs,” he continued. “It is much more difficult to lower Campy in the plant.”

Hofacre was involved in another research project to determine the best time to test broilers on the farm for Campylobacter. They found testing broilers 2 weeks or less prior to processing produces the best results for estimating the Campylobacter and Salmonella loads at processing, he said.

Reducing loads on farm

Another USDA grant enabled Hofacre and colleagues to determine how well biosecurity recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO) worked to reduce Campylobacter on the farm. The research was conducted on a broiler farm with two houses.

The researchers tested three flocks, with the first as baseline. Then they cleaned the two broiler houses following the WHO list of recommendations that ranged from heat-treated litter and formaldehyde fumigation to fly and rodent control. Unfortunately, the houses broke with Campylobacter at 2 weeks.

“It was as if we had done nothing in both houses,” Hofacre said. “We redoubled our efforts and did everything all over again. This time we only delayed when the flocks went positive for one house at 3 weeks and the other at 4 weeks. We were pretty disappointed.”

Beetle suspect

However, the researchers did put out beetle and fly traps knowing that the insects can carry Campylobacter. Beetles did show up at both houses and tested positive for Campylobacter.

“For us in the US, beetles are probably an Achilles heel…for being maintained on a broiler farm and transferring Campylobacter to the broilers,” Hofacre said. “We did trap some flies outside the houses but never isolated Campylobacter from them.”

Another possible route of Campylobacter is through water lines. “You can find Campylobacter on the biofilm of a nipple-drinker water line,” he said. “This indicates that water-line disinfection has to be a part of a control program.”

The future

While Campylobacter is normal flora for broilers and does not impact their performance, it’s a human foodborne illness that the CDC is concerned about.

“We need to reduce the load or amount of Campylobacter coming from broiler farms into processing so the plants can be successful in lowering Campy that goes to consumers,” Hofacre concluded.