By Rosie Whittle, PhD, and Shawna Weimer, PhD

University of Arkansas

A behavioral need encompasses behaviors that chickens are strongly motivated to perform and the inability to perform these behaviors could result in frustration (Duncan, 1998). Behavioral needs are commonly driven by a strong internal motivation, such as hormonal or neuronal triggers, resulting in the behavior being performed in all environments regardless of whether the behavior can be performed satisfactorily (Duncan, 1998). When chickens are unable to fulfill these behavioral needs, they can exhibit a rebound (increase) in the limited behavior. Known behavioral needs of chickens include foraging, preening, and nesting. Dustbathing has also been considered a behavioral need despite being controlled by a combination of internal (circadian rhythm) and external factors (presence of substrate).

Dustbathing occurs in all commercial chicken housing housing systems, even in caged systems with no substrate (Duncan, 1998).

What is dustbathing?

Dustbathing is performed by many wild and domestic birds and may function to removed stale lipids from the feathers and remove ectoparasites (Duncan, 1998). Dustbathing typically occurs every other day and lasts approximately 27 minutes per bout (Vestergaad, 1982). When unable to dustbathe, a buildup of lipids and degradation of feather structure is observed, which is reversible with provision of an appropriate substrate (van Liere et al., 1987). After a period of substrate deprivation, chickens will exhibit a rebound effect where they begin dustbathing faster and for longer compared to when they had daily access to substrate (Vestergaard, 1982). Therefore, dustbathing maintains feather condition and is a highly motivated behavior.

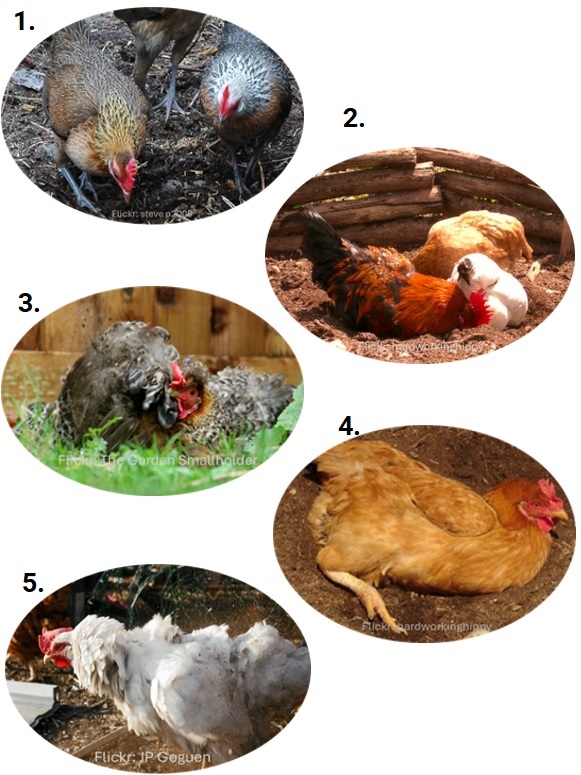

Dustbathing behavioral sequence

- Pecking and scratching at a potential site

- Sitting and bill raking to pull substrate closer

- Vertical wing shake to toss dust particles into the air

- Side lying, rubbing head and side into substrate

- Feather ruffle to shake off loose substrate

(Shields et al., 2004)

Photographer credits, images cropped to shape:

1. Flickr: steve p2008 https://tinyurl.com/flickrstevepj2009

2. Flickr: hardworkinghippy https://tinyurl.com/hardworkinghippydustbath

3. Flickr: The Garden Smallholder https://tinyurl.com/thegardensmallholderdustbath

4. Flickr: hardworkinghippy https://tinyurl.com/hardworkinghippydustbath2

5. Flickr: JP Goguen https://tinyurl.com/jpgoguenruffle

Dustbathing in commercial chickens

Dustbathing can be observed to some extent in all commercial housing systems. In the absence of appropriate substrates, chickens perform an incomplete dustbathing called “sham dustbathing” (Vestergaard, 1998). However, sham dustbathing does not diminish the motivation to dustbathe like a complete sequence of dustbathing does (Olssen et al., 2002). Therefore, only the provision of appropriate substrates can fulfill the behavioral need to dustbathe.

Litter preferences

- Laying hens prefer peat moss and sand to wood shavings and straw for dustbathing (Petherick and Duncan, 1989, van Liere et al., 1990). After litter deprivation, dustbathing increases in sand but not wood shavings (van Liere et al., 1990).

- Broiler chickens prefer sand to rice hulls, wood shavings or shredded paper (Shields et al., 2004).

- Used wood shavings are more attractive for dustbathing than fresh wood shavings providing the used litter remains friable (Moesta et al., 2008).

Caged systems

- Laying hens prefer sham dustbathing on Astroturf than wire, rubber, or slatted floors (Merrill et al., 2006).

- Sham dustbathing usually occurs close to feeders and birds bill rake in the feeder trough to attempt to spread feed (Lindberg and Nicol, 1997)

- Sham dustbathing can result in feather and foot damage (Duncan, 1998)

- Feed is delivered onto scratch mats in enriched cages to encourage dustbathing and foraging

Dustbathing for ectoparasite control?

Ectoparasites such as the red mite and northern fowl mite present welfare concerns for commercial chickens, often resulting in reduced weight gain, anemia, and, in extreme infestations, death (Kilpinen et al., 2005). Chickens respond to mite infections by performing more preening and head scratching (Kilpinen et al., 2005; Murillo et al., 2020). Dustbathing in diatomaceous earth, sulfur and, kaolin (fine clay) boxes provided to hens reduced northern fowl mite presence by 80-100% within one week (Martin and Mullens, 2012). However, dustbathing in sand did not decrease ectoparasites, and dustbathing in feed increased mite numbers (Vezzoli et al., 2015). Consequently, dustbathing only mitigates ectoparasite burden when the substrate has desiccating effects.

Summary

Dustbathing is crucial for feather maintenance, but satisfying this behavioral need is dependent on substrate type. Inadequate substrates can lead to incomplete dustbathing, which may decrease feather quality and cause frustration. Ectoparasites pose a challenge to chickens, but dustbathing in substrates like diatomaceous earth could significantly reduce their numbers.

References

Duncan, I. J. H. (1998). Behavior and behavioral needs. Poultry Science, 77:1766-1772. (https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/77.12.1766)

Kilpinen, O., Roepstorff, A., Permin, A., N., Nørgaard-Nielsen, G., Lawson, L. G., Simonsen, H. B. (2005). Influence of Dermanyssus gallinae and Ascaridia galli infections on health of laying hens (Gallus gallus domestics). British Poultry Science, 46(1): 26-34. (https://doi.org/10.1080/00071660400023839)

Lindberg, A. C. and Nicol, C. J. (1997). Dustbathing in modified battery cages: Is sham dustbathing and adequate substitute? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 55: 133-128. (https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168- 1591(97)00030-0)

Martin, C. D. and Mullens, B. A. (2012). Housing and dustbathing effects on northern fowl mites (Ornithonyssus sylviarum) and chicken body lice (Menacanthus stramineus) on hens. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 26: 323-333. (https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.0097.x)

Merrill, R. J. N., Cooper, J. J., Albentosa, M. J., Nicol, C. J. (2006). The preference of laying hens for perforated Astroturf over conventional wire as a dustbathing substrate in furnished cages. Animal Welfare, 15(2): 173-178. (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600030256)

Moesta, A., Knierim, U., Briese, A., Hartung, J. (2008). The effect of litter condition and depth on the suitability of wood shavings for dustbathing behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 115: 160-(http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2008.06.005)

Murillo, A. C., Abdoli, A., Blatchford, R. A., Keogh, E. J., Gerry, A. C. (2020). Parasitic mites alter chicken behaviour and negatively impact animal welfare. Scientific Reports, 10: 8236. (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65021-0)

Olsson, I. A. S., Duncan, I. J. H., Keeling, L. J., Widowski, T. M. (2002). How important is social facilitation for dustbathing in laying hens? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 79: 285-297. (https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00117-X)

Petherick, J. C., Duncan, I. J. H. (1989). Behaviour of young domestic fowl directed towards different substrates. British Poultry Science, 30(2): 229-238 (https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668908417143)

van Liere, D. W. and Bokma, S. (1987). Short-term feather maintenance as a function of dust-bathing in laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 18(2): 197-204. (https://doi.org/10.1016/0168- 1591(87)90193-6)

van Liere, D. W., Kooijman, J., Wiepkema, P. R. (1990) Dustbathing behaviour of laying hens as related to quality of dustbathing material. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 26(1-2): 127-141. (https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(90)90093-S)

Vestergaard, K. (1982). Dust-bathing in the domestic fowl – diurnal rhythm and dust deprivation. Applied Animal Ethology, 8: 487-495. (https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(82)90061-X)

Vezzoli, G. Mullens, B. A., Mench, J. A. (2015) Dustbathing behavior: do ectoparasites matter? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 169:93-99. (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2015.06.001)

To view all issues of Poultry Press, click here.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.