By Vijay Durairaj, PhD*; Ryan Vander Veen, PhD*; and Steven Clark, DVM**

Huvepharma

Virtually everyone in the poultry industry is aware of coccidiosis — a disease caused by protozoan parasites, Eimeria, that develop within the intestine of most domestic and wild animals and birds. The condition is more elusive in turkeys, however.

Unlike Eimeria that infect chickens, turkey Eimeria do not cause obvious gross lesions in the intestine, and therefore, the disease often goes unrecognized. Under laboratory conditions, clinical signs of coccidiosis are observed in poults at 4 to 6 days after they are inoculated with sporulated viable oocysts.

In contrast, under production conditions, clinical coccidiosis is not usually observed in poults that are less than 10 to 14 days old. The parasite responsible for coccidiosis is always present in turkey flocks irrespective of their ages. The absence of clinical signs of coccidiosis does not guarantee that the parasite has no impact upon the health and performance of the turkey.

It’s been our experience that even mild (subclinical) coccidiosis in turkeys results in malabsorption of nutrients, depression of weight gain and impaired feed conversion. Therefore, an effective coccidiosis-control strategy must be implemented to ensure optimal performance.

Top three

Seven species of Eimeria infect turkeys. Three of these — E. adenoeides, E. meleagrimitis and E. gallopavonis — are considered the highly pathogenic species.1 These three Eimeria species have been identified repeatedly in the major turkey-producing areas of the world.

Due to their protective and resilient wall, coccidial oocysts can survive long periods in the environment, particularly in dust, and can be carried by beetles and flies. The oocyst is resistant to commonly used disinfectants. Birds may also have access to contaminated litter and carry the oocysts miles from their original source.

Survival in dry litter is generally quite short (2 to 5 days) as the oocyst is susceptible to desiccation. However, in moist litter, the oocysts may survive for many weeks. If the oocysts become buried in moist dirt, there have been reports of survival of the oocysts for over 1 year.

Diagnosing coccidiosis

In turkeys, making a definitive diagnosis of clinical coccidiosis is complicated. Diagnostic methods include clinical signs, gross lesions in the intestine and evaluating the oocysts from mucosal scraping and/or feces.

Clinical signs of coccidiosis are like those of several other causes of enteritis. However, evaluation of gross lesions in the intestines, which is commonly performed in chickens, is considered by most to be an unreliable diagnostic method for turkeys.

Visible lesions of coccidiosis are not common in turkeys, even in severe infections. Experimental studies, in which poults were inoculated with high numbers of oocysts, showed variable correlations between lesion scores and weight gain and mortality; a high number of studies demonstrate severely depressed weight gains with no significant lesions or mortality.

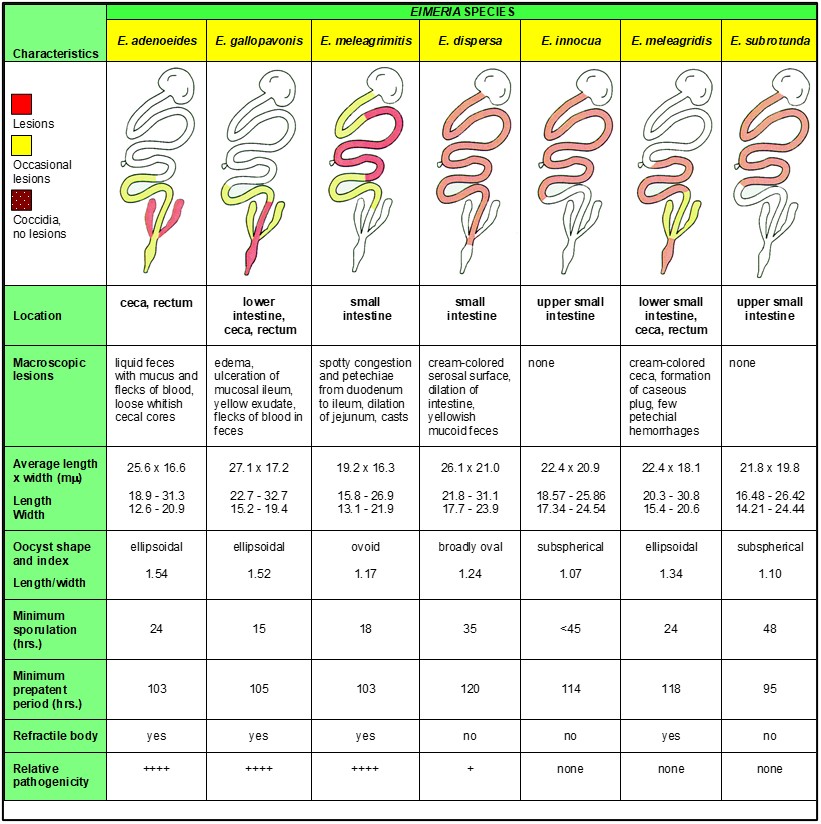

Occasional mucosal sloughing is characteristic only of nonspecific enteritis — not of a specific Eimeria species or level of infection. Although mucosal scrapings can be used to identify the presence of oocysts, variations in oocyst size and distribution in the intestine contribute to the complexity of speciating turkey Eimeria and diagnosing clinical coccidiosis (Table 1).

Table 1. Diagnostic characteristics of Eimeria species in turkeys (Roche, 1995)A

AAdapted from Reid WM, Long PL, McDougald LR. Coccidiosis. Hofstad MS, Barnes HJ, Cainek BW, Reid WM, Yoder Jr. HW. (Eds.) Dis. Poult. 8th ed. Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames Iowa, U.S.A. 1984;692.

Other protozoa

Several types of protozoa are associated with enteric disease of turkeys. Protozoal enteritis can present with general signs, including dehydration, loss of appetite (off-feed), loose droppings and watery intestinal contents. Flagellated protozoa include Cochlosoma, Tetratrichomonas, Histomonas and Hexamita. Cryptosporidia and Eimeria are non-flagellated protozoa of turkeys.

Cochlosoma and Hexamita are associated with enteritis, primarily in young turkeys, especially in the summer months. There are field reports of coinfections with flagellated protozoa, such as Cochlosoma and Tetratrichomonas, or Cochlosoma and Hexamita, and Eimeria. Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic examination of the mucosal scrapings.

Peak shedding

Routine monitoring of commercial turkey flocks shows that oocyst levels normally peak at 4 weeks of age, even in healthy flocks.

Observations have noted significantly higher oocyst levels in cecal samples than intestinal samples. Oocyst levels in cecal droppings average 10 times higher than respective intestinal droppings. The cecal droppings are usually excreted a couple times per day in the morning and evening hours, with a creamy consistency. Fecal droppings are normal, firm consistency defecated multiple times during the day. This may be due to the ceca concentrating oocysts and subsequently releasing its contents infrequently.

Major oocyst excretion occurs from 4 to 6 weeks of age, but low excretion was observed until market age. E. dispersa and E. meleagrimitis were most common between 4 to 6 weeks of age. E. adenoeides was found to occur in high numbers at all ages, with peak outputs at 2 to 4 and 12 to 14 weeks of age.

Impact on intestinal health

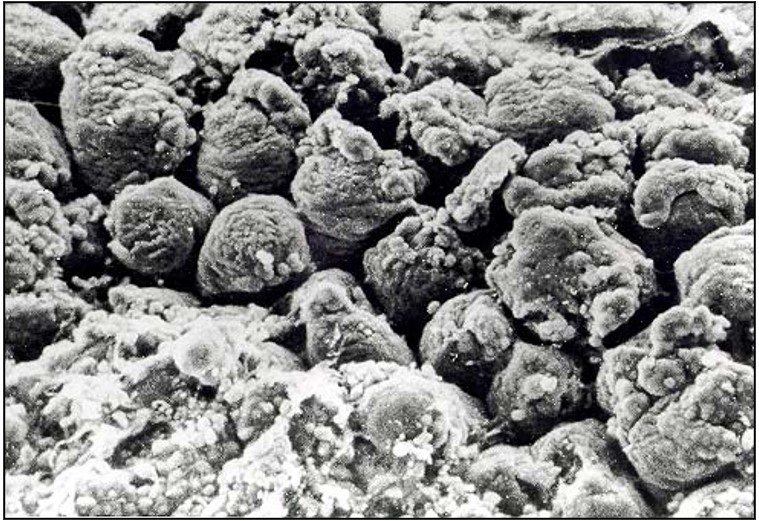

A scanning electron photomicrograph of the ileum from a turkey infected with E. adenoeides at 6 days post-inoculation demonstrates the potential intestinal damage caused by coccidiosis; the villi are markedly shortened with gaps in the microvillar layer (Figures 1 and 2). Such damage would reduce absorption of nutrients and growth performance of the bird.

Figure 1. Scanning electron micrograph (approximately 650X) of ileum from uninfected 3-week-old turkey poult (photo provided by: P. Augustine)

Figure 2. Scanning electron micrograph (approximately 650X) of ileum from 3-week-old turkey poult infected with Eimeria adenoeides at 6 days post-inoculation (photo provided by: P. Augustine)

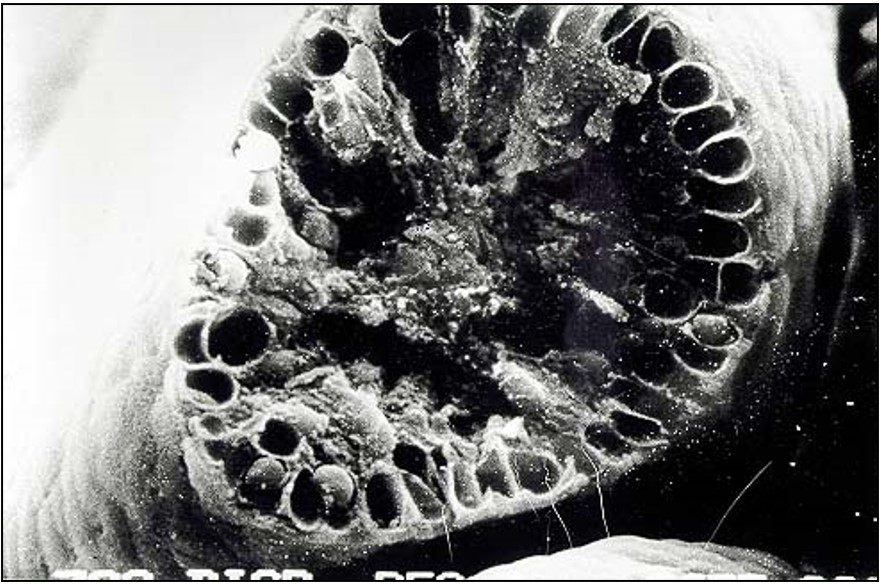

In another study, although no gross lesions were observed, additional electron microscopy exemplifies that each cell includes vacuoles with numerous Eimeria oocysts (Figure 3). Consequently, nutrient absorption would be reduced, despite the apparently normal intestinal villi upon gross examination.

Figure 3. Scanning electron micrograph (approximately 650X) of intestine, fractured transversely, from 3-week-old turkey infected with Eimeria dispersa at 6 days post-inoculation (photo provided by: P. Augustine)

Controlling coccidiosis in turkeys

Coccidiosis continues to rank as a top concern among turkey health professionals. The trend toward “no-antibiotics-ever” (NAE) production in recent years forced many producers to discontinue using ionophores —a class of antibiotics that had proven effective against coccidiosis. Some production schemes also prohibit the use of FDA-approved non-ionophore anticoccidials. In these situations, producers have had to rely on phytogenic supplements and/or vaccination.

Proper vaccination results in repeated exposure to the Eimeria species, which occurs because of recycling of the oocysts through the poults, allowing subsequent development of protective immunity. Until recently, coccidia vaccination involved using a live, oral two-strain vaccine (Immucox® T) that contains sporulated oocysts of E. adenoeides and E. meleagrimitis. In April 2024, Huvepharma received conditional license from USDA to begin manufacturing and marketing a live vaccine that protects against three strains of Eimeria: E. adenoeides, E. meleagrimitis and E. gallopavonis. It is sprayed onto day-old turkey poults in the hatchery.

Producers have two types of FDA-approved medications available for managing coccidiosis in turkeys:

- Ionophores such as lasalocid (Avatec®) and monensin (Coban®). As noted earlier, ionophores are a class of antibiotics and therefore cannot be used in NAE programs.

- Non-ionophore anticoccidials such as amprolium (Amprol® 25%), diclazuril (Clinacox®); and zoalene (Zoamix® and ZoaShield™) may be used in rotation programs throughout the year or a shuttle program in the same flock, with ionophores.

Early anticoccidial medication is important to control infection in the poults. Many effective anticoccidials have a dosage-range approval to prevent coccidiosis. The immunity that turkeys develop during the first part of the grow-out because of exposure to coccidia can prevent the occurrence of clinical signs of infection in turkeys as they get older. Extended use of anticoccidials or successful vaccination are part of an effective coccidiosis-control strategy.

Nutritional dietary supplementation with phytogenic chemicals may be provided through the feed or drinking water. Programs may utilize phytogenics in addition to the current anticoccidial program to potentiate the possible benefits or as the sole supplement for coccidia control.

Some phytogenics have purported activity against coccidia. Phytogenics consist of “alternative” products including organic acids, yeast, phytonutrients from plant extracts (saponin, yucca, etc.) and essential oils (oregano, carvacrol, thymol, cinnamaldehyde, capsicum oleoresin, turmeric oleoresin). Essential oils may be natural extracts or synthetic nature-identical compounds.

Phytogenics and vaccines may be used to supplement the current ionophore or non-ionophore anticoccidial program, or as the sole program for coccidia control. Non-ionophores and ionophores also may be used as a sole program or may be shuttled in the flock, such as for example, non-ionophore during the brooding phase followed by an ionophore in the later grow-out period.

Understanding coccidia and how coccidiosis damages the birds’ intestines, and hence flock health and resulting performance, is imperative to be able to develop the appropriate practices to implement effective control. New and innovative products will further help meet the needs of the turkey industry.

* Huvepharma, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

** Huvepharma, Inc., Peachtree City, Georgia, USA.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.

1 Chapman HD. Coccidiosis in the turkey. Avian Pathol. 2008;37(3):205-223, DOI: 10.1080/03079450802050689