Although poultry production has steadily evolved with improved knowledge and technological advances, coccidiosis remains arguably the most important disease concern to keep in mind and address year after year.

“It’s an issue from the past that continues to be recycled in the present,” said Hector Cervantes, DVM, MS, DACPV, honorary MAM, University of Georgia, in a presentation about coccidiosis at the 2024 Poultry Science Association annual meeting.

Old challenge still highly relevant

Cervantes began his talk by referencing a quote from a scientific review paper published in 1950, attributed to pioneering coccidiosis researcher P.A. Hawkins:

“Coccidiosis is today a much studied, widely known and little understood disease of poultry.”

“Here we are 74 years later, and I can open with the same statement,” Cervantes said.

“We have learned a lot about coccidiosis. But at the same time, there is so much we have yet to learn. It remains an ubiquitous disease that requires significant financial expenditure to control. Coccidiosis is present in every flock and is something veterinarians and producers must always keep front of mind.”

Embezzler more than thief

Fortunately, much progress has been made to improve the understanding of coccidiosis and ensure more effective management. At the same time, it’s important not to take coccidiosis control for granted.

“Don’t underestimate the potential costs of this issue,” he said. Cervantes relayed to the audience what his colleague, John Barnes, DVM, PhD, told him years ago:

“Remember, coccidiosis is not a thief, it’s an embezzler. With a thief, the damage is immediately apparent — you are robbed instantly. With the embezzler, things remain pretty quiet until you balance the books. In the case of coccidiosis, when you settle the flock, you realize, whoa, what happened?”

A given farm can easily observe five points worse feed conversion and 30 points less weight gain if coccidiosis is not fully mitigated, he said.

Coccidiosis basics

Cervantes provided a recap of coccidiosis fundamentals, sprinkled with insights for keeping this issue — still arguably the long-reigning king of poultry diseases — at bay:

The disease

Coccidiosis is a protozoal disease of the intestinal tract of animals that has consistently been among the most important disease concerns of poultry production. It is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria that infect different segments of the intestinal tract, destroying epithelial cells. This destruction leads to inflammation, increased permeability, malabsorption of nutrients, impaired growth, poor feed utilization, increased mortality and susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections.

“Poultry become infected when pecking at the litter, and the severity of infection is related to the number of sporulated oocysts ingested,” said Cervantes. In general, infection and immunity are species-specific — an important consideration when anticoccidial vaccines are considered for prevention.

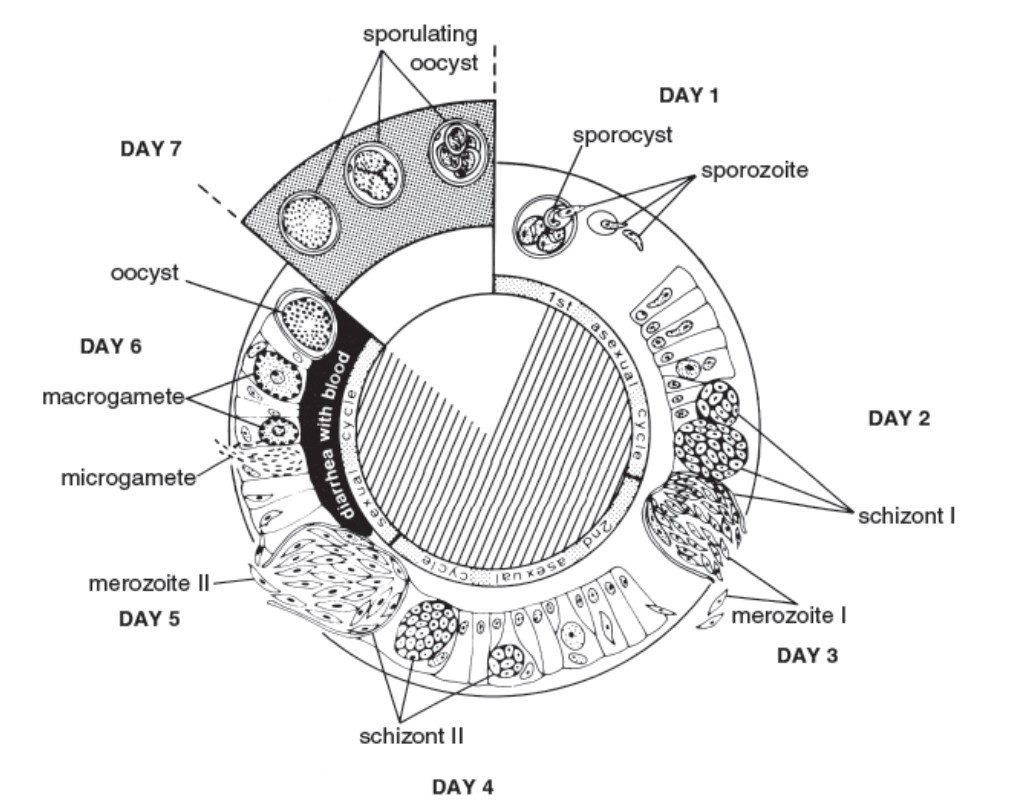

Coccidia of poultry have direct life cycles, with an exogenous phase (sporogony) taking place outside the host in the litter and the endogenous phases (schizogony and gametogony) occurring inside the host (see illustration below*).

Coccidiosis is a self-limiting disease. After two or more asexual cycles of multiplication (schizogony), the parasites sexually differentiate into microgametocytes (male cells) or macrogametocytes (female cells).

Fertilization produces oocysts that are voided in the droppings onto the litter to close the cycle. When excreted, the oocysts are unsporulated (not infective). But with the proper temperature, oxygen and moisture, they sporulate and become infective within 24 to 48 hours.

The diagnosis

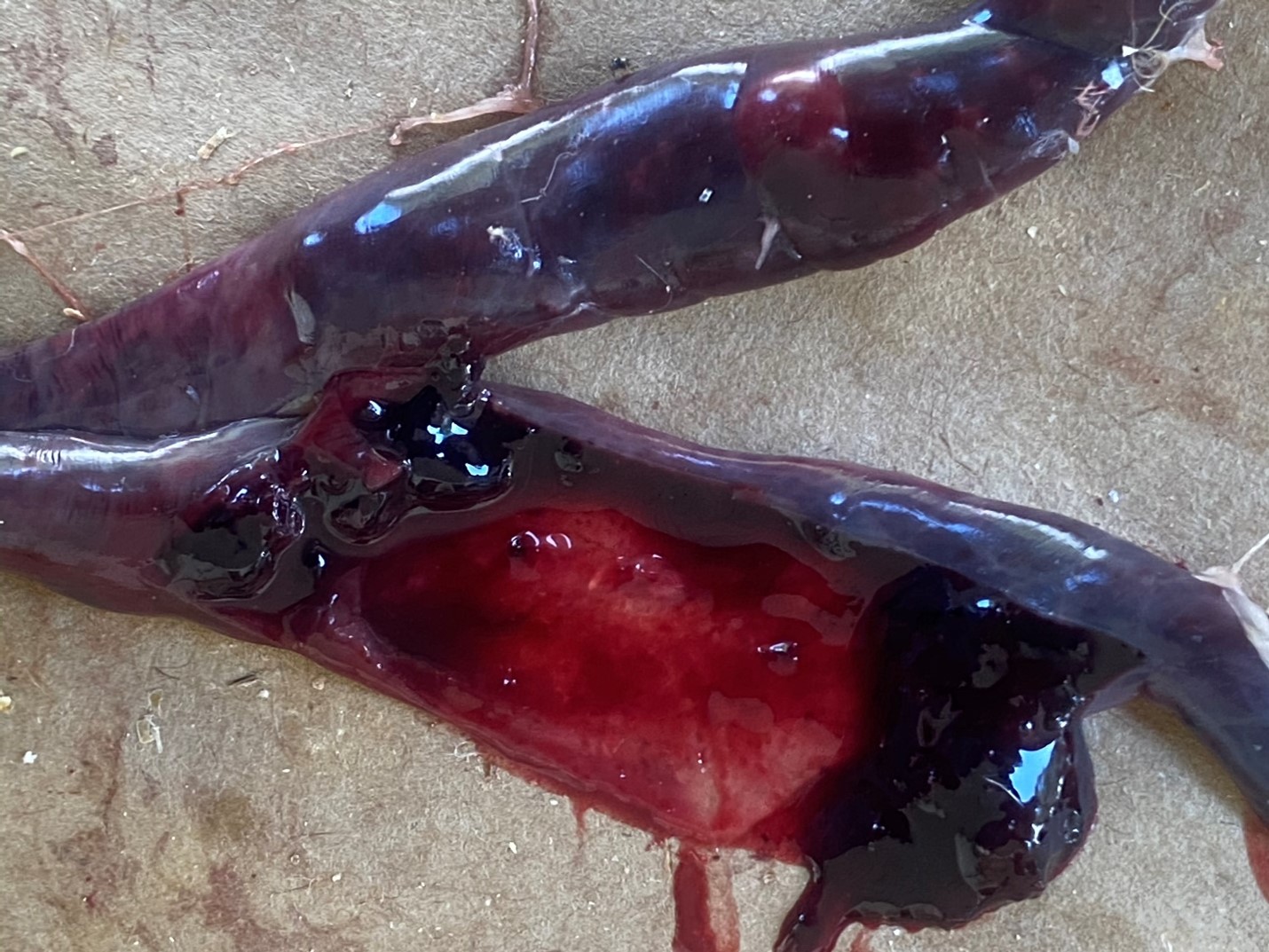

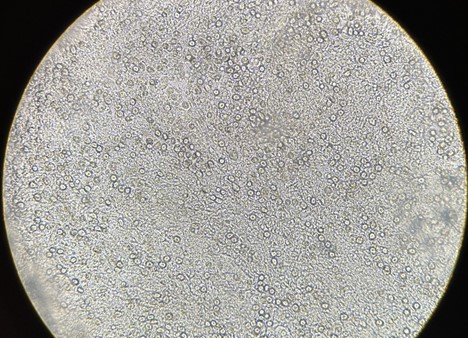

A definitive diagnosis of coccidiosis requires diagnostic testing. In chickens, five species of coccidia (E. acervulina, E. brunetti, E. maxima, E. necatrix and E. tenella) produce gross lesions in specific intestinal regions, microscopic observation of different stages of the parasite in mucosal scrapings taken from the intestines or the ceca should be used to confirm the diagnosis.

In turkeys, three highly pathogenic species (E. adenoides, E. gallopavonis and E. melagrimitis) can produce lesions under experimental conditions. However, gross lesions are rarely found in the field, and diagnosis is primarily based on identifying parasitic forms with microscopic examination of intestinal mucosal scrapings.

Since coccidiosis (a mild coccidial infection not impacting performance) is so prevalent, the finding of a few coccidial oocysts does not warrant a diagnosis of coccidiosis.

He noted that histopathology and molecular tests are primarily used in research due to cost and time requirements.

Lesion scoring

Although lesion scoring has been practiced since the 1950s, a standardized system was not widely adopted until 1970 when Johnson and Reid published a detailed description of gross lesions for each of the five species that produce gross lesions in chickens.

In 2019, a similar system for scoring gross lesions of the three most pathogenic species of turkeys was published by Gadde et al., although the common lack of gross lesions has hampered its application in the field.

Seeking a better understanding

Despite all that is known about coccidiosis, Cervantes said a lot is still a mystery. For example:

- Why does the coccidiosis that infects chickens not infect turkeys and other birds?

- What are the factors that make coccidiosis so resistant to environmental conditions?

- What makes sporozoites invade cells in specific segments of the intestinal tract?

- What makes sporozoites within the same location invade epithelial cells at the tips of the villi and others the crypts?

- Why is the infection self-limiting?

- What determines whether some third-generation merozoites will become microgametocytes or macrogametes?

“These are just a few examples,” Cervantes said. “Overall, we still know very little.”

What is certain is that coccidiosis has been and will remain one of the most important diseases of poultry for the foreseeable future, he said.

“The key to management is to know it’s there, even if you don’t see it. Although the main species shows clinical signs, such as diarrhea, other species don’t. It makes sense to take steps to control the disease every year to keep the highest health and performance potential for your flock.”