When weekly mortality rates in layer flocks older than 50 weeks start creeping up over 0.3%, producers and veterinarians should be suspicious.

According to Eric Gingerich, DVM, a technical services specialist at Cargill’s Diamond V, these numbers could indicate the presence of Escherichia coli, a stealthy culprit of late-stage mortalities.

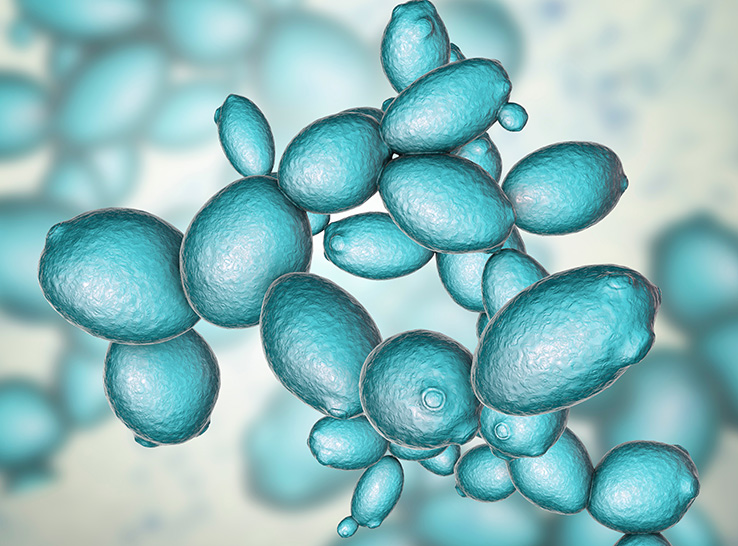

E. coli preys on weakened, passive low-weight birds that lack competitiveness. Wounds sustained from scratching or pecking, especially in poorly feathered birds, grant the pathogen access to infect.

Birds jumping down from multi-level tiers in cage-free aviaries can break yolks internally. E. coli growth flourishes in the abdominal cavity in this broken-yolk material.

Although mortalities due to late-stage E. coli infection may not be widespread, producers and veterinarians shouldn’t dismiss the issue.

The loss of valuable laying hens, reduced egg production and potential impact on flock health and welfare are just some of the damages that can result.

Here, Gingerich offers practical advice on curtailing late-stage mortalities caused by this prominent bacterial infection afflicting bird health and farm profitability.

What common risk factors predispose layer flocks to late-stage E. coli mortalities?

EG: For starters, upper respiratory tract diseases such as infectious bronchitis, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, infectious coryza and avian metapneumovirus are notorious for leading to secondary bacterial infections, of which E. coli is the main offender.

Other respiratory challenges that help E. coli do damage are high-dust environments and excess ammonia levels. Levels above 20 ppm compromise the respiratory tract, so dust, which is basically fecal material, can deeply invade.

Coliform-contaminated water is another problem area. E. coli in water lines leads to an imbalanced intestinal microflora, resulting in higher levels of E. coli excreted in feces. This higher E. coli load increases infection levels via wound, intra-oviduct and respiratory routes.

Two other risk factors are flighty or crowded flocks and poor feathering. Flighty or crowded flocks wound each other more frequently than normal-activity flocks, and wounds provide a direct pathway for E. coli infection. Poorly feathered birds are also at risk because they lack the protection a good feather cover gives and, therefore, get wounds more easily.

An issue often seen with cage-free layers involves unequal use of equipment for feed, water and nests. This inequality creates excessive competitiveness and crowding, leading to poor flock uniformity; small, susceptible birds; and immune suppression.

The stress these low-end-weight birds experience is not to be underestimated, as it is immunosuppressive and makes them more vulnerable to E. coli infection.

What indicators of late-stage E. coli mortalities should producers be on the lookout for?

EG: Potential indicators include mortality rates exceeding 0.3% per week and necropsies revealing lesions of caseous peritonitis, pericarditis, perihepatitis or oophoritis on the majority of freshly dead birds.

Are there measures to differentiate mortalities due to late-stage E. coli infections from other causes?

EG: Routine necropsies of fresh dead birds help identify causes of mortality. If E. coli is a problem, the percentage of birds with lesions of caseous peritonitis, pericarditis, perihepatitis or oophoritis will be high.

An accurate diagnosis requires submitting swabs from the lesions to a diagnostic lab where they can culture them and determine if E. coli is the source of infection or another bacteria, such as Salmonella spp., Gallibacterim anatis or Pasteurella multocida.

What management and biosecurity practices can help control the incidence and severity of late-stage E. coli mortality in flocks?

EG: Producers should try to obtain a high flock uniformity of pullets and maintain that through lay. Achieving this will help immensely.

As mentioned earlier, birds on the low end of the weight curve are typically more stressed. They’re not eating or drinking enough due to their lack of competitiveness. This heightened stress level is immunosuppressive, making them easy prey for E. coli infection.

Dead birds should be removed daily to avoid exposing flockmates to these potential sources of E. coli.

Additionally, thoroughly removing water-line biofilms between flocks followed by continuous water chlorination — I recommend chlorine dioxide — will help eliminate E. coli or other bacteria that can lead to dysbacteriosis.

What can be done in terms of flock-health management to mitigate late-stage E. coli mortalities?

EG: One effective strategy is vaccination with a live E. coli vaccine, with the vaccine administered two to three times during growing and, in some cases, again as a booster in lay two to three times.

Feed additives can also help. Prebiotic, probiotic, postbiotic and phytobiotic feed additives can help support healthy gut microflora, reducing E. coli shed into the environment and thus lowering exposure. Likewise, these additives can support the immune system’s response and help strengthen gut-wall integrity to resist E. coli invasion.

For farms with a history of E. coli challenges, mortality rates can be dramatically affected when producers choose birds with more genetic resistance to infections. Bird strains with better feathering fall into this category.

Feathers are a vital barrier to infection, so producers should work with a nutritionist, avoid crowding and add enrichments in cage-free systems to optimize feather cover.

As producers face pressure to reduce antibiotic use, what alternative strategies have shown promise in controlling and preventing E. coli infections?

EG: A somewhat new approach to administering the live vaccine is by eyedrop rather than the usual water or spray methods. The live vaccine can also be mixed with the three-way, killed Salmonella Enteritidis/infectious bronchitis/Newcastle vaccine and injected at 12 to 14 weeks of age. Another option is to inject a killed vaccine at 12 to 14 weeks in addition to two live applications.

In cage-free operations, some producers have begun to clean and disinfect the house at night during mid-lay. While the birds are asleep, they remove the litter and apply disinfectant to the floor.

A postbiotic-phytogenic combination feed additive has shown promising results for layers. A noticeable reduction in the rate of late-stage E. coli mortalities was observed in a field trial of layers.1

The trial compared two same-strain flocks in the same complex, all birds the same age. One flock was fed their usual additive; the other was fed the phytobiotic-postbiotic one.

The lowered rate of mortalities in the flock fed the phytobiotic-postbiotic additive was such that it convinced the producer to switch additives.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.

1 Logue C, Johnson T, Gingerich E, Riggs S, Farmer M. Exploring postbiotic-based strategies for the mitigation of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in layers. Proceedings of 2022 Western Poultry Disease Conference. p. 127.