By Angela Perretti and Shawna Weimer, PhD, University of Arkansas

The ancestor of the modern-day chicken, the red jungle fowl, was exposed to different spectra of light in their natural habitat (Prescott et al., 2003). The surrounding environment, vegetation, season, and time of day all affect the color of light exposure to the wild bird (Endler, 1993), which may have lingering behavioral effects on present-day poultry.

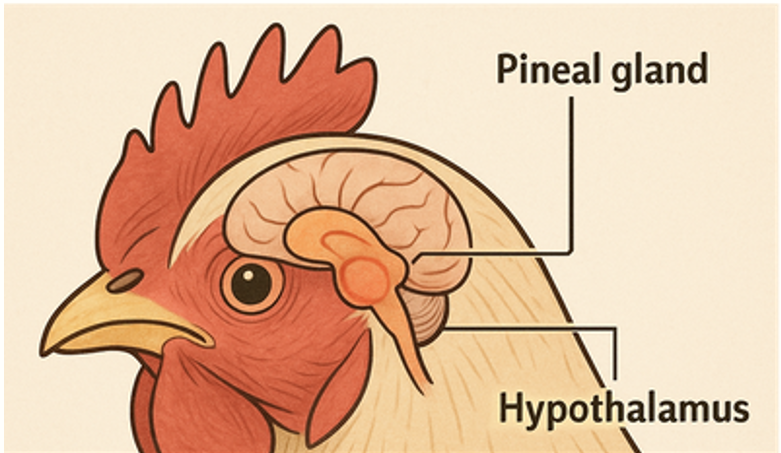

Light impacts many behavioral, endocrine, physiological, and immunological aspects of poultry and can be used as a tool to manipulate their health, production, and welfare (Olanrewaju et al., 2006; Lewis & Morris, 2006). Poultry have advanced visual systems and see the world differently than humans, which influences their behavior (Lewis & Morris, 2006; Franco et al., 2022). Additionally, areas of the brain (e.g. hypothalamus, pineal gland) penetrated by light initiates many important reproductive and hormonal changes (Lewis & Morris, 2006).

Light and poultry vision

- Light: Amount of radiant energy emitted per second onto a surface, has three main characteristics: intensity, photoperiod and wavelength

- Wavelength: A numeric value measured in nanometers (nm) that determines the length of the electomagnetic wave and the color of light (Benoit, 1964)

Visual structures

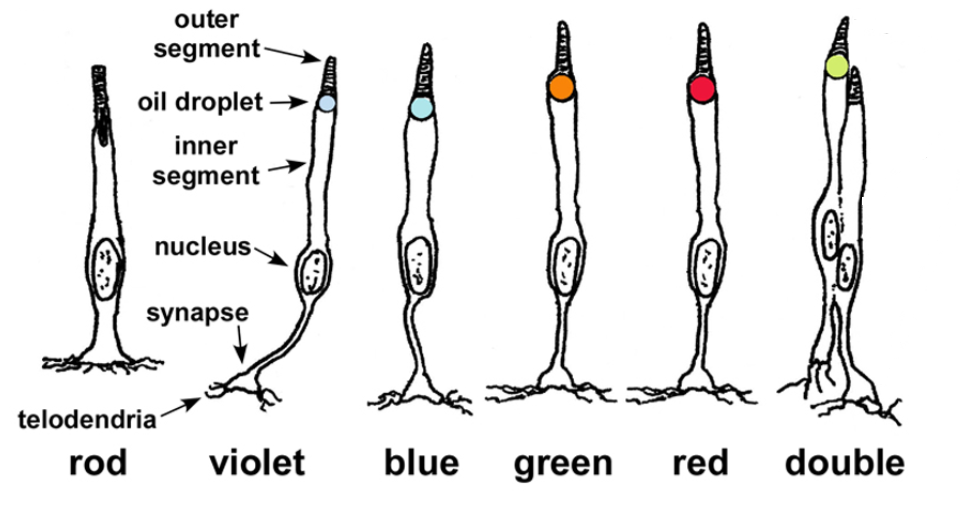

- Like humans, poultry have photoreceptor cells in their retinas called rods and cones (Lewis and Morris, 2006).

- Rods: Highly sensitive to light and aid in seeing in low-lit environments

- Cones: Responsible for color vision and distinguishing color

- Poultry also have distinct visual features different than humans (Lewis and Morris, 2006) (see figure below):

- Oil droplets: Processes different colors of light

- Double–cone receptors: Helps in color vision below 400nm (ultraviolet)

Color perception

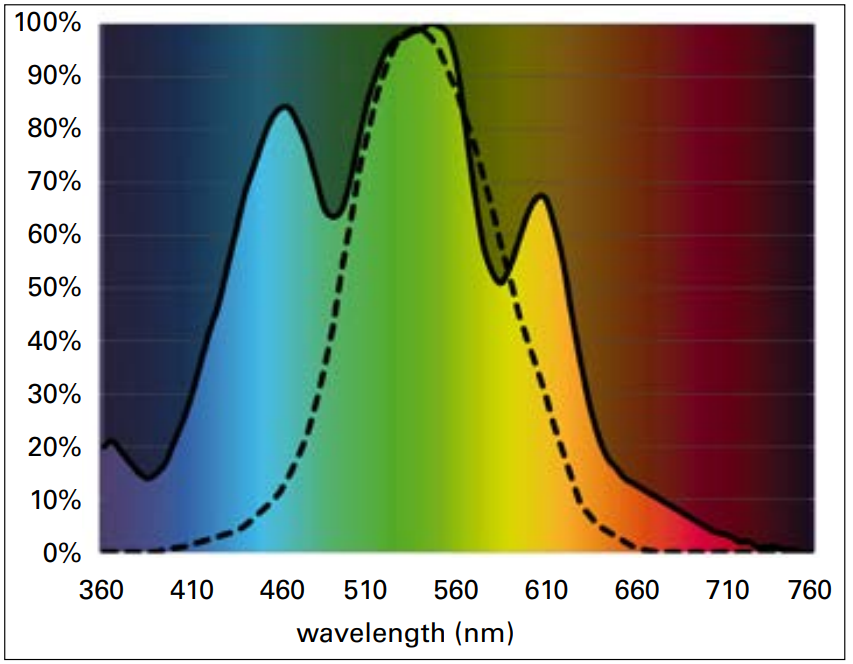

- Birds see a broader spectrum of color compared to humans.

- Human color vision (dotted line) compared to avian species (solid line) share peak sensitivity within 545-575nm (green light) (Franco et al., 2022) (see figure below).

An example of the difference between human and bird vision is in the images below of a clutch of eggs. A human’s color perception of the eggs is on the left and what bird are believed to see is on the right (see figures below).

For more information on the Avian Visual System refer to PEC Newsletter Vol. 10.

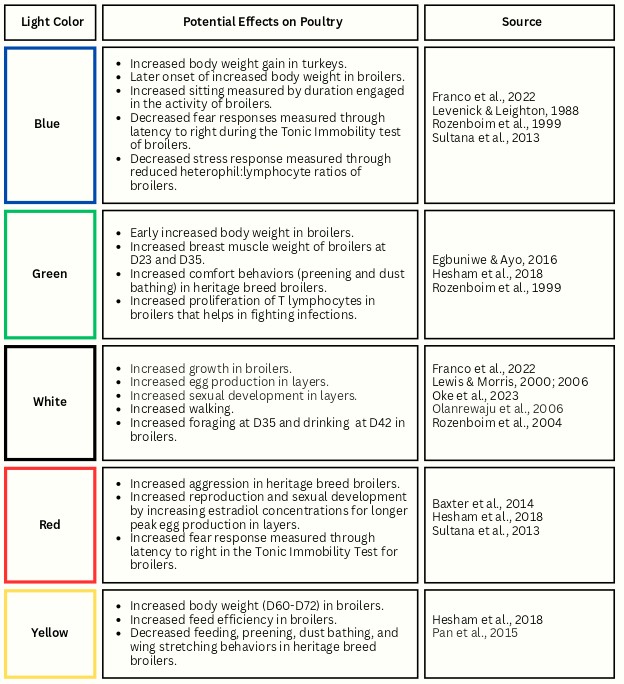

How colored light affects poultry: Behavior and production

Turkeys, broilers, and laying hens may differ in their response to the same light color due to variations in their visual systems, which influence how they perceive light.

How colored light affects poultry: Hormones

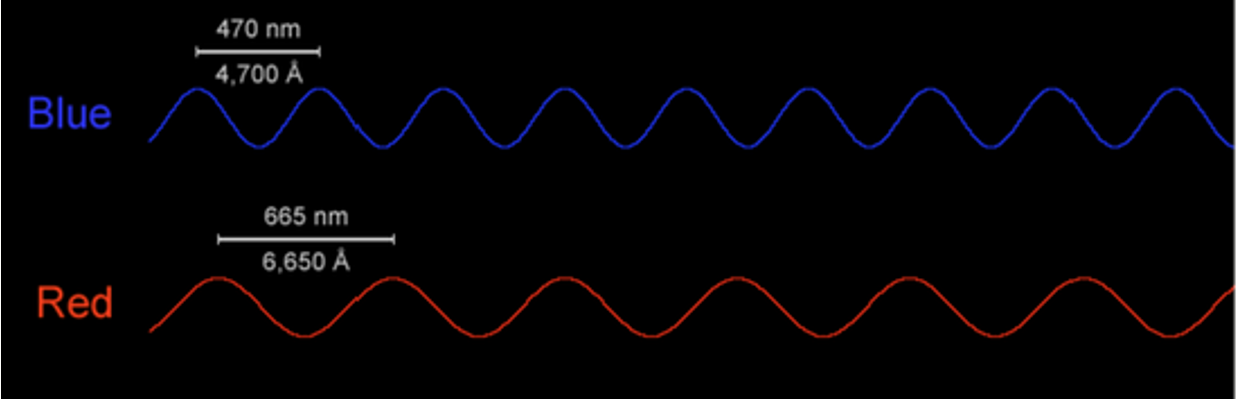

- Colored light has different energy capacities to reach a given surface dependent on their wavelength.

- Light information from the environment needs to penetrate through layers of skin and bone to reach the photosensitive pineal gland and hypothalamus.

- Long wavelengths (red light) are more effective at penetrating those layers compared to short wavelengths (blue light) because the light can maintain a longer duration of exposure (Benoit, 1964).

- This occurs regardless of the light intensity and schedule.

- Melatonin is released in darkness from the pineal gland (see figure below), while light exposure suppresses its production (Olanrewaju et al., 2006)

- Luteinizing hormones (LH), follicle-stimulating hormones (FSH), or gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH) are released when the hypothalamus (see figure above) receives light signals (Lewis and Morris, 2006).

- The hypothalamus and the pineal gland help regulate hormone secretion, behavior, immunity, and the reproductive system (Lewis and Morris, 2006, Piesiewicz et al., 2012; Abdel-Moneim et al., 2024).

- Birds will reach sexual maturity depending on when GnRH are released and how much is released.

- This affects the reproductive system by stimulating the output of testosterone in males and estrogen in females.

- The reproduction cycle of poultry can be manipulated with the use of colored light to induce reproductive behaviors (e.g., egg-laying) outside of their typical cycle. This allows producers to maintain year-round egg-laying and reproductive practices.

DID YOU KNOW?

A breed of chicken called the Smoky Joe has been genetically selected for blindness (retinal degeneration), yet can still perceive light indirectly through their brain (Baxter et al., 2014).

Colored lighting applications

Variable lighting

- Colored light can be used interchangeably to elicit positive results in:

- Production (feed intake, FCR, BW)

- Performance (carcass and parts yield)

- Stress (heterophil: lymphocyte ratio)

- Broilers raised in green then blue light had improved feed efficiency at day 28 of age, and

birds raised in white, green, then blue light had reduced heterophil: lymphocyte ratios (HLR),

which suggests a low long-term stress response (Zamanizad et al., 2019). - Broilers raised in white then blue light at D26 had improved FCR (Cao et al., 2012).

- Blue lights can be used during shackling at processing plants to keep broilers calm (Barbosa

et al., 2013). - Given that producers can adjust light intensity and photoperiod, introducing variable colored

lighting may be a simple solution for improved production. - When considering improving production with colored lighting schedules, the potential

increase in growth could affect locomotion and leg health. Thus, it is important to be aware

of the overall flock health before altering their environment.

Preference tests

- Presenting animals with choice gives insight into their preferences, which is important to

their welfare (Senaratna et al., 2012). Using differently colored lit areas allows for the

opportunity for autonomy and choice for poultry (Senaratna et al., 2012). - Layer pullets spent more time in blue lighting compared to white, green, and red when given

the opportunity (Li et al., 2018). - Broilers had a greater preference for red light and the lowest preference for green light at

day 28 when given a choice with different colored lights in each room (Senaratna et al., 2012). - The understanding of poultry color vision is still in its infancy (Lewis & Morris, 2006), but

allowing birds to choose which color they prefer may give insights to how they differentiate

between spectra. Additionally, giving animals a choice in their environment promotes their

welfare.

Practical considerations for colored light

Welfare costs

- Current commercial poultry practices may use different colored light depending on the age and phase of production.

- For example, in layer production, red light can be used to increase egg production. However, increasing egg production can be detrimental to their welfare by increasing the risk of keel and leg bone fractures (Toscano et al., 2020).

- Using colored light to manipulate body weight gain in poultry can lead to potential welfare issues. For example, severe increased growth of broilers increases risk of mobility issues, leg health issues, footpad dermatitis, or poor feather cleanliness (Zhou et al., 2024).

Monetary costs

- LEDs are cost effective tools (Thomson & Corscadden, 2018), however the initial set-up of a lighting program with color-changing LEDs can be expensive.

- Lighting programs should be based on the goals of the producer. Additionally, installing color-changing lights may require assistance from lighting companies.

Concluding remarks

- Poultry perceive color differently than humans, so this should be considered when designing lighting schedules and programs.

- The wavelength of a light determines how effectively it can reach a bird’s hypothalamus and pineal gland.

- Chickens and other poultry have multiple photosensitive organs and glands besides the retinas, that when stimulated with light elicit hormonal, behavioral, and

reproductive responses. - Allowing poultry to chose their preferred light color can give insights into their color vision and enhance their welfare.

- The cost of initial installation of LEDs for light color-changing systems may be high compared to incandescent lighting, but LEDs are more energy efficient and are available in different spectras.

- Light can easily be installed and used as a non-invasive tool to promote improved health, performance, and production of poultry.

References

Abdel-Moneim, E. A. M., Siddiqui, S. A., Shehata, A. M., Biswas, A., Abougabal, M. S., Kamal, A. M., … & Teng, X. (2024). Impact of light wavelength

on growth and welfare of broiler chickens–overview and future perspective. Annals of Animal Science, 24(3), 731-748.

Barbosa, C. F., Carvalho, R. H. D., Rossa, A., Soares, A. L., Coró, F. A. G., Shimokomaki, M., & Ida, E. I. (2013). Commercial preslaughter blue light

ambience for controlling broiler stress and meat qualities. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 56, 817-821.

Baxter, M., Joseph, N., Osborne, V. R., & Bédécarrats, G. Y. (2014). Red light is necessary to activate the reproductive axis in chickens

independently of the retina of the eye. Poultry Science, 93(5), 1289-1297.

Benoit, J. (1964). The role of the eye and of the hypothalamus in the photostimulation of gonads in the duck. Annals of the New York Academy

of Sciences.

Cao, J., Wang, Z., Dong, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, J., Li, F., & Chen, Y. (2012). Effect of combinations of monochromatic lights on growth and productive

performance of broilers. Poultry Science, 91(12), 3013-3018.

Egbuniwe, I. C., & Ayo, J. O. (2016). Physiological roles of avian eyes in light perception and their responses to photoperiodicity. World’s

Poultry Science Journal, 72(3), 605–614. on-invasive tool for improving animal welfare and wellbeing.

Endler, J. A. (1993). The color of light in forests and its implications. Ecological monographs, 63(1), 1-27.

Franco, B. R., Shynkaruk, T., Crowe, T., Fancher, B., French, N., Gillingham, S., & Schwean-Lardner, K. (2022). Does light color during brooding

and rearing impact broiler productivity?. Poultry Science, 101(7), 101937.

Hesham, M. H., El Shereen, A. H., & Enas, S. N. (2018). Impact of different light colors in behavior, welfare parameters and growth performance

of Fayoumi broiler chickens strain. Journal of the hellenic veterinary medical society, 69(2), 951-958.

Levenick, C. K., & Leighton Jr, A. T. (1988). Effects of Photoperiod and Filtered Light on Growth, Reproduction, and Mating Behavior of Turkeys:

1. Growth Performance of Two Lines of Males and Females. Poultry science, 67(11), 1505-1513.

Lewis, P. D., & Morris, T. R. (2000). Poultry and coloured light. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 56(3), 189-207.

Lewis, P. D.; Morris, T. R. (2006). Poultry lighting: the theory and practice. Nottingham University Press.

Li, G., Li, B., Zhao, Y., Shi, Z., Liu, Y., & Zheng, W. (2019). Layer pullet preferences for light colors of light-emitting diodes. Animal, 13(6),

1245-1251.

Oke, O. E., Oso, O., Iyasere, O., Oni, A., Bakre, O., & Rahman, S. (2023). Evaluation of light color manipulation on behavior and welfare of broiler

chickens. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 26(4), 493-504.

Olanrewaju, H. A., Thaxton, J. P., Dozier, W. A., Purswell, J., Roush, W. B., & Branton, S. L. (2006). A review of lighting programs for broiler

production. International journal of poultry science, 5(4), 301-308.

Pan, J., Yang, Y., Yang, B., Dai, W., & Yu, Y. (2015). Human-friendly light-emitting diode source stimulates broiler growth. PloS one, 10(8),

e0135330.

Piesiewicz, A., Kedzierska, U., Podobas, E., Adamska, I., Zuzewicz, K., & Majewski, P. M. (2012). Season-dependent Postembryonic Maturation of

the Diurnal Rhythm of Melatonin Biosynthesis in the Chicken Pineal Gland. Chronobiology International, 29(9), 1227–1238.

Prescott, N. B., Wathes, C. M., & Jarvis, J. R. (2003). Light, vision and the welfare of poultry. Animal welfare, 12(2), 269-288.

Rozenboim, I., Biran, I., Uni, Z. E. H. A. V. A., Robinzon, B. O. A. Z., & Halevy, O. R. N. A. (1999). The effect of monochromatic light on broiler

growth and development. Poultry science, 78(1), 135-138.

Rozenboim, I., Piestun, Y., Mobarkey, N., Barak, M., Hoyzman, A., & Halevy, O. (2004). Monochromatic light stimuli during embryogenesis

enhance embryo development and posthatch growth. Poultry science, 83(8), 1413-1419.

Senaratna, D., Samarakone, T. S., Madusanka, A. A. P., & Gunawardane, W. W. D. A. (2012). Preference of broiler chicken for different light colors

in relation to age, session of the day and behavior. Tropical Agricultural Research, 23(3).

Sultana, S., Hassan, M. R., Choe, H. S., & Ryu, K. S. (2013). The effect of monochromatic and mixed LED light colour on the behaviour and fear

responses of broiler chicken. Avian Biology Research, 6(3), 207-214.

Thomson, A., & Corscadden, K. W. (2018). Improving energy efficiency in poultry farms through LED usage: a provincial study. Energy Efficiency,

11(4), 927–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-018-9613-0

Toscano, M. J., Dunn, I. C., Christensen, J. P., Petow, S., Kittelsen, K., & Ulrich, R. (2020). Explanations for keel bone fractures in laying hens: are

there explanations in addition to elevated egg production?. Poultry Science, 99(9), 4183-4194.

Zamanizad, M., Ghalamkari, G., Toghyani, M., Adeljoo, A. H., & Toghyani, M. (2019). Effect of sequential and intermittent white, green and blue

monochromatic lights on productive traits, some immune and stress responses of broiler chickens. Livestock Science, 227, 153-159.

Zhou, S., Watcharaanantapong, P., Yang, X., Thornton, T., Gan, H., Tabler, T., … & Zhao, Y. (2024). Evaluating broiler welfare and behavior as

affected by growth rate and stocking density. Poultry Science, 103(4), 103459.

To view all issues of Poultry Press, click here.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.