As most producers know, poultry performance can suffer during periods of high temperature. Modern housing is designed to maintain environmental temperatures within an optimal range, but how does the temperature of individual birds impact their weight gain?

A recent field study by the University of Georgia looked at the relationship between weight gain and body temperature in broilers.

Normal life processes, including digestion, produces heat. A fast-growing broiler produces 6 British thermal units (Btu)/hour per pound of body weight. Putting this in perspective, burning one matchstick produces 1 Btu/hour.

To maintain a consistent body temperature, this heat needs to be removed, which presents a problem in hot weather. Birds are adapted to keeping warm and controlling heat loss but they have limited behaviors for cooling themselves.

Keeping their cool

When birds are too hot, they can’t perspire. Their main options for cooling themselves are losing body heat to the air around them and panting — a process that increases the amount of air passing through the mouth, nasal passages, lungs, and air sacs to remove the warm moisture.

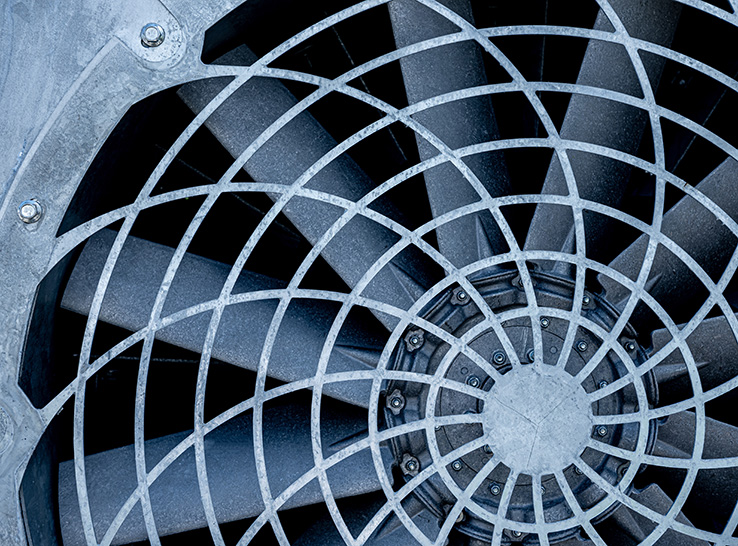

As temperature and humidity rise, losing heat to the air and by respiration become increasingly less efficient. Modern poultry housing is equipped with tunnel air inlets and fans to increase airflow and remove the heat produced by the birds, but how does a bird’s individual body temperature impact feed conversion?

“Studies have shown that feed intake decreases and feed conversion suffers when birds are hot,” says Brian Fairchild, PhD, professor and extension poultry scientist. “This recent study connects body temperature to weight gain.”

Impact on performance

The University of Georgia conducted a field study with eight 34-day-old boilers on a commercial farm. With a pen set up in one of the houses, eight birds ingested a small temperature logger that recorded their body temperature once every minute. Investigators weighed these birds at the beginning of the study and then again 5 days later.

To maintain the same number of birds per square foot as the rest of the house, researchers added an extra 20 birds to the pen. They also measured house air temperature, relative humidity and airspeed every minute. Temperatures ranged from the mid-70s to mid-80s F and airspeed averaged approximately 500 ft/min over the duration of the study.

The normal body temperature for these birds is around 106o F. The average recorded temperature of the subject bids ranged between 106.5o F (normal) and 108.8o F high). In the two birds with temperatures over 108o F, one bird lost weight and one didn’t gain weight. The two birds with the lowest average body temperatures (106.5o F) had the most weight gain, about 1.3 pounds over the 5 days.

Better feed conversion

This, and other studies show there can be a wide variation of individual body temperatures within a house, Fairchild says.

Variations can be due to the location of individuals within a house, density in the vicinity of a given bird, bird size, genetics, feed status, health and other factors. One of the birds with an elevated temperature had symptoms of a minor respiratory infection.

“The fact remains whether an elevated body temperature is due to illness or insufficient heat removal due to ambient temperatures and relative humidity, a bird’s response will be the same; it will eat less, gain less weight and have worse feed conversion,” Fairchild notes.

Air movement critical

Removing excess heat from poultry housing during periods of hot weather helps ensure birds maintain their body temperature, maximizing weight gain, feed conversion, livability and well-being. If birds need to pant to cool themselves, their performance suffers. Fairchild cautions that even when nighttime temperatures drop during periods of hot weather, it’s still important to keep fans running to remove the heat birds produce.

A question that inevitably arises is, “Can market-aged birds be cooled too much during the summer?”

Fairchild says birds can expend a lot of energy trying to keep cool, but in most cases, being too cool isn’t a concern when talking about birds that are four weeks of age or older during hot weather.

“Older birds are well adapted to conserve heat and keep warm. As a result, during hot weather it’s far safer with market-aged birds to maximize air movement over the birds 24/7 rather than turning fans off at night for fear of ‘chilling’ the birds,” he explains.

‘Experienced eyes’

Fairchild notes when it comes to management, “There is no substitute for experienced eyes on the birds.”

He states that while this study was limited in scope, it reinforces the importance of removing heat from the birds as a basic hot weather management practice.

“Optimal house wind speed will help maintain the bird’s body temperature resulting in more feed consumption and more weight gain,” Fairchild says.