Past knowledge can provide useful insight to control the latest outbreak of avian metapneumovirus in the US poultry industry, according to two leading experts on the disease.

Metapneumovirus has up to a 50% mortality rate, with morbidity in flocks often reaching 100%. But, when the virus emerged on US turkey farms in 1996, it was “an enigma to us from the very beginning,” explained David Halvorson, DVM, University of Minnesota.

Cases in Colorado provided the first positive diagnoses. From there, research groups quickly started building a knowledge base, Halvorson told an audience at a webinar on avian metapneumovirus sponsored by the American Association of Avian Pathologists.

Historical overview

There are three types of the virus: A, B and C. Types A and B were only recently detected in the US. Scientists showed that the first outbreak in the US in 1996 was type C virus, with origins in a single introduction from wild birds.

Research teams in MN and USDA developed new diagnostic testing capacity for the Type C virus outbreak. Researchers also determined that the virus was immunosuppressive, with immunosuppression severity depending on the type of secondary infections birds faced.

Halvorson’s team proved airborne transmission over short distances in the lab. With evidence of neonatal infection from type A and B cases in Europe, they subsequently demonstrated that vertical transmission in the US was also possible.

Vertical transmission warranted breeder vaccination as the recommended approach to best protect newly-hatched birds, he said. Other research teams quickly developed different vaccine options, some of which were developed into one commercial USDA approved product that was widely used.

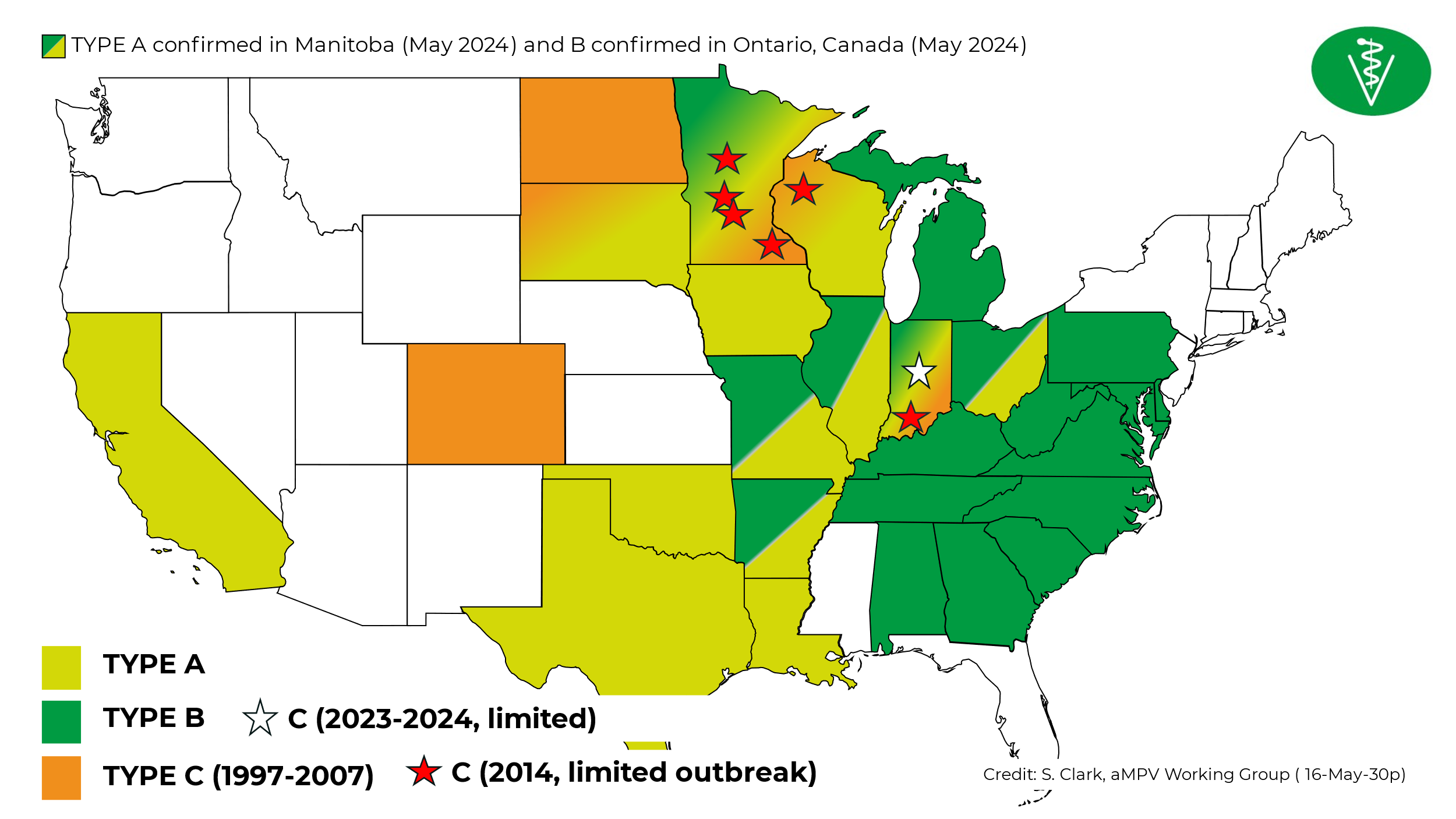

Type C began to disappear around 2007, with the outbreak considered over in 2008. Although there was a limited Type C outbreak in 2014, the virus has not troubled poultry producers until the outbreaks of Types A and B now. (Figure 1).

Figure 1

New outbreak prompts mobilization

The latest emergence of the disease started in late 2023, explained Steven Clark, DVM, veterinary technical service manager, turkeys, at Huvepharma.

This time around, all three types of the virus have been confirmed, again with close geographic links to wild-bird migration routes, Clark noted. A 200-strong (and growing) working group of poultry veterinarians, researchers, and regulatory and animal-health professionals across the US has quickly mobilized to tackle the outbreak.

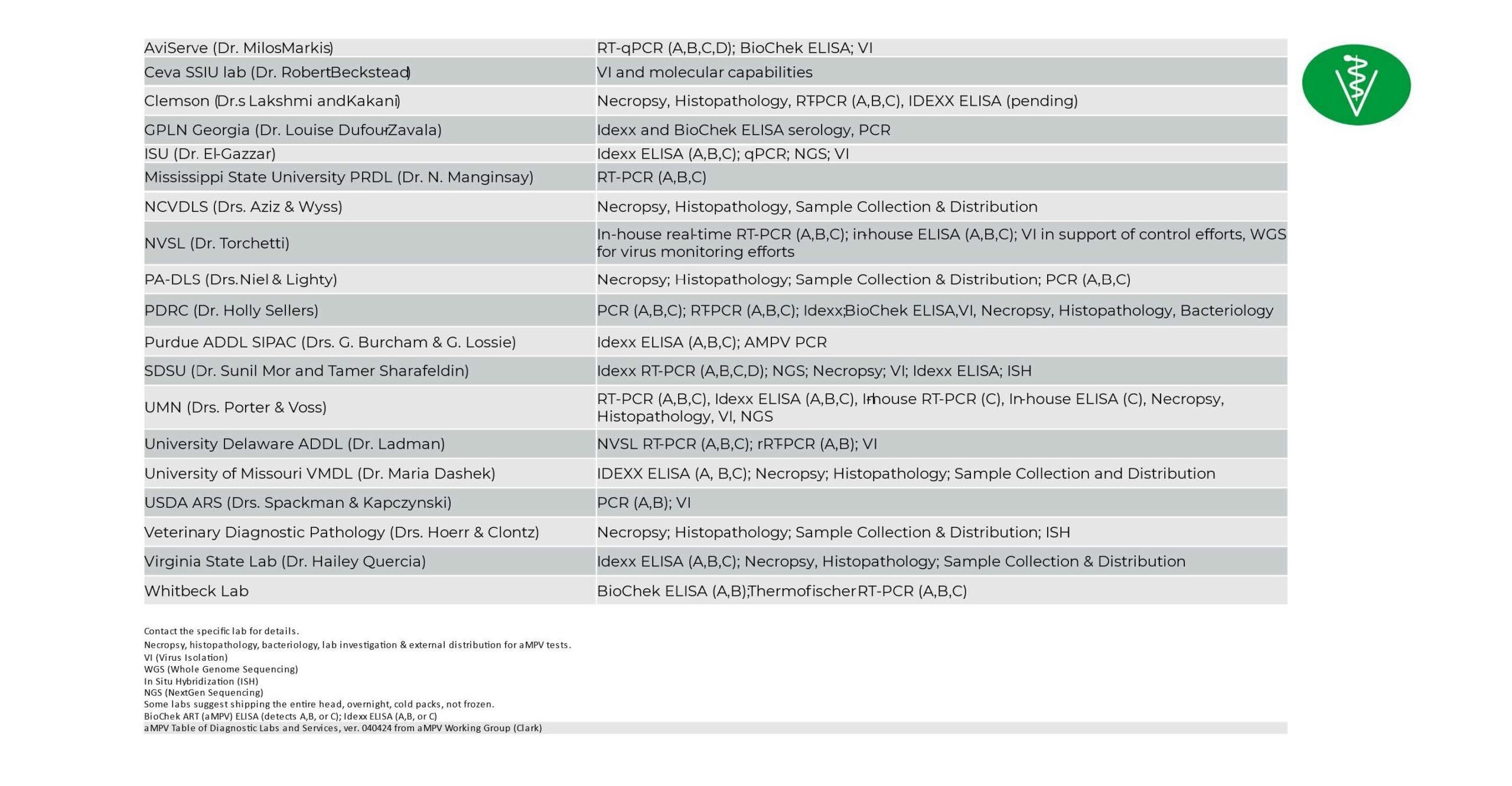

“Within a month or two, we compiled a long list of diagnostic support labs across the country. (Figure 2). [It is] just amazing to see the work that everybody has done to come together to provide tools that we can use to help diagnose this disease,” Clark said.

Figure 2

Profound flock impacts

Serology on affected turkey farms in North Carolina has tended to show entire flocks infected with avian metapneumovirus, with the virus quickly spreading through entire operations with 3 to 4 weeks this winter, he continued. Clark added that it starts in the brooder house and is transferred to finisher farms.

Beyond turkeys, it has also affected broilers and broiler breeders, as well as chicken layers.

Seasonal weather conditions can play a crucial role, Clark noted, pointing to a facility that lost 26% of its flock in the first 3 weeks of infection after transfer from a brooder farm in cold weather to an unheated finisher facility.

There are multiple signs of infection in affected birds, he explained. Some of the key diagnostic features of infection include sinusitis, facial cellulitis and a crust around the eyes. There have also been cases with neurological signs, (star-gazing, torticollis) caused by secondary E. coli infections entering the skull and inner ear.

“The disease is acute. One day you could have a few birds with mild clinical respiratory signs. The following day, the whole flock is infected,” he said.

Biosecurity focus

Currently, there are no USDA-licensed vaccines against the disease, so biosecurity needs to be the primary focus for producers, Clark explained. Biosecurity efforts that were implemented during the 1996-2006 outbreak set an example, with new measures to reduce direct and indirect contact with wild birds and improve practices with moving crews and equipment.

Improved ventilation and water sanitation are part of the latest efforts to minimize the outbreak’s impact, he noted. Many of the biosecurity measures are the same as those established to combat the highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks that have recently affected the US poultry industry.

“We now have reports that flocks, even in the brooder house, can remain asymptomatic after infection if we can manage them well and keep them comfortable, without secondary bacterial or viral challenges, or environmental stresses,” Clark said.

Sample collection, vaccine hopes

With the current outbreak, there have also been new developments regarding sample collection. Diagnostic laboratories request for whole heads and necks submitted, sent overnight on ice packs but not frozen, Clark continued. Freeze-thawing affects scientists’ ability to complete effective testing, he said.

Timing of the sampling is also crucial because secondary infections can reduce the chances of recovering metapneumovirus using PCR, and the virus appears to be present only during the first few days of the clinical signs.

Though the impact of improved diagnostics and biosecurity is apparent, the vaccination question remains. Most recently a few labs have successfully isolated the virus, which can be used for commercial production and approval of USDA vaccines against aMPV. With genome sequencing showing that the type B currently circulating is very similar to European isolates, there is also interest in importing vaccines to use in prevention programs.

“The US industry realizes that we need a killed vaccine for the breeder program and a live vaccine be administered for broilers and turkeys and breeders, to successfully control aMPV,” he added.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.