Three poultry scientists from Penn State University — Kayla Niel, DVM, Megan Lighty, DVM, PhD, and Jonathan Elissa, DVM — answer questions about HPAI vaccination and whether it should be considered for US flocks.

Why vaccinate for HPAI?

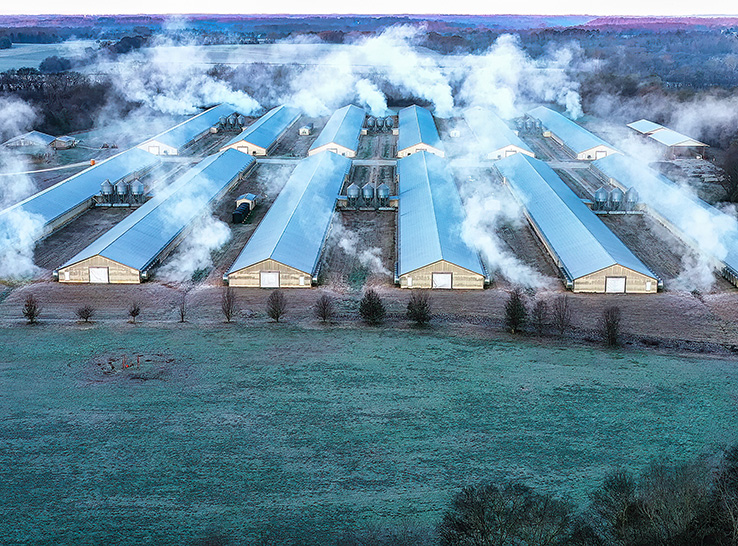

As the 2022-2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak continues, there is growing concern that “stamping out” programs alone are expensive and labor intensive, and therefore not sustainable. This has led to growing interest in AI vaccines, perhaps allowing vaccines to become an additional “tool in the toolbox” to combat HPAI. The advantages and disadvantages of vaccinating are being closely evaluated by the USDA and other stakeholders here in the US and around the world.

Vaccinated birds are likely to have increased resistance to avian influenza virus infection and decreased replication of the virus in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. This should lead to reduced viral shedding, thus resulting in reduced environmental contamination, reduced spread amongst and between premises, and reduced transmission to domestic and wild birds. Vaccination could potentially add an extra layer of protection in addition to enhanced biosecurity measures but cannot replace these biosecurity measures.

Does HPAI vaccination prevent infection?

No, vaccination does not prevent infection. Vaccinated birds may still become infected with field strains of the virus and serve as a source of virus for spread to other flocks. However, vaccinated birds are likely to have increased resistance to infection and decreased shedding of the virus. This should result in reduced environmental contamination, reduced viral spread, and reduced transmission to other domestic flocks.

If a vaccinated bird or flock becomes infected, depopulation would still be required. Enhanced biosecurity measures must still be taken to reduce the chances of virus introduction into domestic birds, even if vaccinated.

Are HPAI vaccines available in the US?

At this time, there are no approved vaccines for the current (2022-2023) HPAI outbreak strain available for use in the US. While there are some commercially produced AI vaccines available, none are an exact match for the strain of the virus that is currently circulating in the US and would likely prove ineffective or inefficient.

Although new vaccines that would be a better match to the virus strains currently circulating are in the process of being developed, there are several other potential issues that need to be considered by the USDA and other stakeholders. These issues include production capabilities, logistical considerations, regulatory and trade implications, and legal licensing requirements. If a suitable, effective vaccine candidate becomes available in the US, it would have to go through certain approval processes before use is permitted. Once approved, sufficient quantities would have to be produced and distributed appropriately.

USDA must also discuss and negotiate with trade partners to ensure that international trade could continue if vaccines were implemented. Disruption of the United States’ $6 billion poultry export business would result in significant economic loss and loss of jobs within the poultry industry. As such, experts believe it may be at least another 2 to 3 years before HPAI vaccination is a viable option in the US.

Have HPAI vaccines been used in previous outbreaks?

Vaccines have never been approved or used to control HPAI in the US. However, in the past, there has been occasional limited use of specific vaccines to control low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI). The implications and considerations for an LPAI outbreak are significantly different than that of an HPAI outbreak, however, and the vaccines used in those scenarios would not be effective or efficient in combatting the current HPAI virus.

Are HPAI vaccines being used in other countries?

Previously, 14 countries vaccinated against HPAI to combat outbreaks during the years 2002-2010. This use was considered preventive or emergent and was in addition to stamping out programs. Vaccine use has not become routine in these countries. Other countries where HPAI is considered to be endemic, such as China and Mexico, employ routine HPAI vaccination. It is important to note that the virus strains used for vaccination in these other countries match those of previous outbreaks, not the current 2022-2023 outbreak.

The European Commission recently harmonized vaccination rules across the EU for avian influenza for poultry, meaning that the regulatory hurdle barring EU member states from vaccinating is likely to be removed very soon. The Commission states that the new rules are in line with World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) standards and sets out conditions that allow movement of vaccinated animals and their products.

What would a potential AI vaccination schedule look like?

Similarly, to other poultry diseases, best protection would likely be attained with a prime/boost vaccination schedule. This type of multiple dose vaccination would certainly be required for longer-lived birds such as layers and breeders and possibly turkeys. A single dose vaccination would be very unlikely to offer sufficient protection.

Birds would likely be “primed” with a live recombinant vector vaccine (such as HVT-AI) administered via injection at the hatchery. They would then likely need to be “boosted” on the farm at least once with an inactivated or killed injection. Ideally, the killed vaccination on the farm would be a combination vaccine, containing different antigens for broader immune response and protection.

Application of these injectable vaccines would be quite labor intensive, requiring individual handling of all birds for vaccination.

How would HPAI vaccination change testing and surveillance?

Current surveillance programs rely heavily on serology testing, which detects antibodies in the serum (blood). Birds produce antibodies after an exposure, whether naturally exposed to a field virus or exposed to antigens in a vaccine. With our current surveillance programs, we would have difficulty differentiating vaccinated birds from naturally infected birds. A diagnostic testing method that can differentiate infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) is required to allow detection of naturally occurring infections and depopulation of infected birds.

There are several possible approaches for DIVA, but the options will vary depending on the field situation and vaccine type used. Each local scenario would likely need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and would still require trade partner acceptance before implementation could be approved. Surveillance programs may need to shift from predominantly serologic-based surveillance to molecular (PCR) techniques and may require up to three times as many samples and/or sampling dates. Another option could be the use of unvaccinated, sentinel birds. These options would be more expensive than current testing and surveillance programs.

How would HPAI vaccination change product movement?

According to the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), vaccination will not affect the HPAI-free status of a country or zone if surveillance supports the absence of infection. As such, vaccine use would not necessarily affect international trade if certain requirements were met, but individual trade partners must agree. USDA will have to negotiate with major trade partners and continue to provide needed assurances that exported products are free of the virus. This will require adequate administration of appropriate and approved vaccines with implementation of surveillance programs that allow differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA).

Disruptions to the international export market would likely prove devastating to the poultry industry and the US economy. The US poultry export business is estimated to be worth $6 billion dollars and supplies hundreds of thousands of jobs in the country. Even if your company or business does not directly engage in international trade, others in the state and the country certainly do. The decision to vaccinate could negatively affect their continuity of business if not carried out diplomatically.

Rules and regulations regarding interstate movement of products would also need to be reviewed and likely changed. Several states currently have rules that would make it extremely difficult if not impossible to import birds or products from AI vaccinated flocks into the state.

If the US decides to pursue HPAI vaccination, it will still likely be at least 2 to 3 years before implementation is possible. In the meantime, biosecurity is the best and most important tool we have to prevent HPAI infection. For biosecurity resources, please visit the USDA APHIS Defend the Flock Program website and review the National Poultry Improvement Plan 14 principles of biosecurity.