By Samantha Vitek and Leonie Jacobs, PhD

Virginia Tech

What is the pre-slaughter phase?

The preslaughter phase is the last phase of the broiler chicken’s life before slaughter.

This phase includes multiple steps: withdrawal of feed and water, catching, loading into transportation crates, and transportation by road, In some cases, chickens may be placed in lairage (waiting area) after arrival at the processing plant. The chickens are then removed from crates, shackled on the processing lines, and stunned prior to actual slaughter.

The last three steps may vary in order depending on the stunning method. Different aspects of broiler welfare are at risk of being compromised during the pre-slaughter phase.

This article will focus on the animal welfare risk factors in this pre-slaughter phase.

Feed and water withdrawal

The first step in the pre-slaughter phase is feed and water withdrawal. Feed is normally withdrawn before catching to reduce the risk for foodborne illness in people.

A feed withdrawal time of 8 to 12 hours (includes catching, loading, transport, and lairage) prior to slaughter is recommended, and in some countries legally requires (Wabeck, 1972), although longer periods of withdrawal sometimes occur. Water access is typically removed just prior to catching.

If prolonged, this period without feed and water may lead to hunger, weight loss, thirst, dehydration, and distress (Delezie et al., 2007; Najafi et al., 2016; Nijdam et al., 2005; Vanderhasselt et al., 2013).

Catching and loading

Broilers need to be caught and loaded into transportation crates. The catching process should occur in dim light to minimize bird activity and stress.

Birds can be manually and mechanically caught, usually by contracted professional catching crews. In some countries this is done by acquaintances of the producer.

When they are manually caught, birds are picked up by both their legs, carried upside down, and then loaded into containers with plastic crates or drawer systems. Catchers can carry 5 birds in each hand (National Chicken Council, 2022). The containers are loaded onto the truck by forklift.

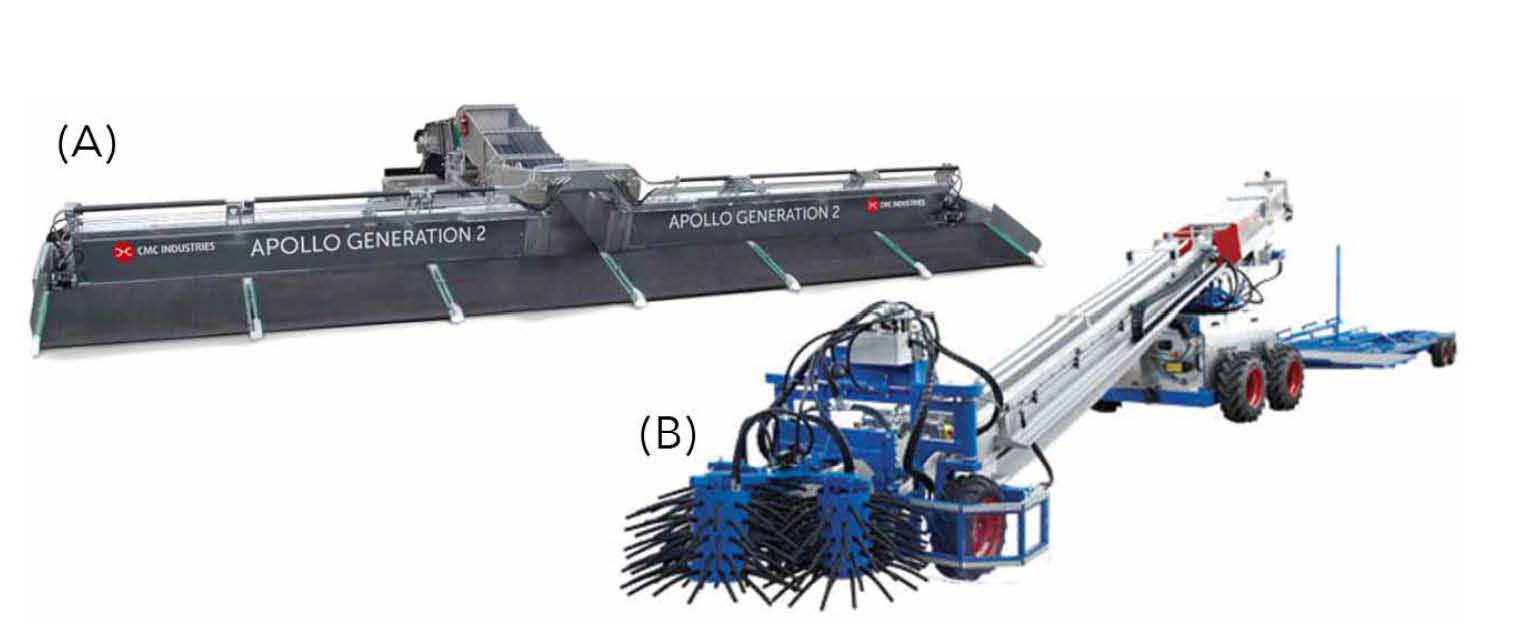

In some cases, birds are mechanically caught, where a vehicle with a conveyor belt or rotating ‘rubber fingers’ is driven through the barn to catch and load birds into crates. Birds are never inverted and not manually caught or carried.

Mechanical and manual catching systems are both used in the United States. The benefits of mechanical catching are that it is lower in cost and has improved working conditions, such as less physical labor (Lacy & Czarick, 1988).

Catching and loading may cause fear, distress, injuries, and death (Chauvin et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2017; Jones, 1992; Kannan & Mench, 1996; Kittelsen et al., 2018; Nijdam et al., 2006).

The risk factors for broiler welfare during the catching and loading process include catching crew, catching duration, rough inverted handling, catching method (animal handling), and catching environment (lighting).

Risks of catching and loading

Catching crew, catching duration

The choice of catching crew matters. The prevalence of bruising on breasts and wings tended to differ depending on which catching crew was involved (Jacobs et al., 2017).

Prolonged catching results in more welfare issues, including bruising, scratching, and fractures (Jacobs et al., 2017).

Manual versus mechanical catching

Manual catching tends to have a more negative impact on broiler welfare than mechanical catching:

- Greater risk of bruised legs and bruised wings (Smith & Pierdon, 2023), more bruised wings (7.7% vs 4.2%, Delezie et al., 2006), more bruising overall (3% vs 2%, Knierim & Gocke,2003).

- More fractures (0.9% vs 0.7%; Knierim &Gocke, 2023) and dislocations (0.6% vs 0.5%).

- Higher stress and fear levels (Delezie et al.,2006).

However, in some cases manual catching scoresbetter then mechanical catching:

- Fewer wing fractures and bruises (Ekstrand, 1998).

- Fewer dead-on-arrivals at the slaughter house (Chauvin et al., 2011; Ekstrand, 1998).

Upright versus inverted handling

An alternative to the conventional inverted catching method or mechanical catching is an upright catching method.

Although rarely applied, birds can be carried upright by their abdomen, which shows many improvements for animal welfare, especially injuries (Kittelsen et al.,2018). Upright handling is required for GAP certification (Global Animal Partnership,2018).

Birds that are caught upright, are less fearful (Jones, 1992), showed a reduced acute stress response (Kannan & Mench,1996), show less agitation (de Lima et al.,2019), and have fewer wing fractures (Kittelsen et al., 2018) compared to birds exposed to inverted handling. Catching may take more time because workers can only carry two birds.

Catching environment (lighting)

Light intensity should be reduced to a minimum during catching.

High light intensity (lux) can increase acute stress responses (Wolff et al., 2019).

Two mechanical catching machines that can be used to catch and load broilers for transportation to the slaughter plant. A) The Apollo harvester from CMC industries (poultry.cmcindustries.com/apollo-generation-22123746787.html) using conveyor belts to pick up birds, and place them in crates. (B) The Chicken Cat from JJ Conveying (adapted from chickencat.eu/uk/features.aspx). Image from Jacobs & Tuyttens, 2020.

Transportation

Once birds are loaded onto the truck, they are driven to the slaughter plant.

These transportation trucks may have tarps, curtains or ventilation doors to protect birds from extreme weather, but in some cases no such protections are in place.

Transportation to the slaughterhouse may elicit acute stress (Delezie et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 1992), and death in extreme circumstances (Chauvin et al., 2011; Nijdam et al., 2004; Vecerek et al., 2006).

Stocking density in crates, thermal load, weather conditions, and duration of transportation are all risk factors for broiler chicken welfare.

High crate stocking density

Bird welfare can be at risk when transported under high densities (little space allowance):

- Strong acute stress response(corticosterone) (Delezie et al., 2007).

- Strong chronic stress response (H:L ratio) (Bedánová et al., 2006).

- Higher dead-on-arrival rates (Chauvin et al., 2011; Nijdam et al., 2004).

Birds should be upright and crated in a single layer, allowing space to sit comfortably. The appropriate crate stocking density depends on bird size and climatic conditions.

Weather conditions

In cold weather conditions, birds may be huddling together, indicating thermal discomfort (too cold). In hot weather, birds may spread out and pant, also indicating thermal discomfort (too warm).

These conditions may risk bird welfare:

- Birds experienced cold stress when they were near air inlets (Knezacek et al., 2010).

- Birds experienced heat stress in poorly ventilated areas of the truck (Knezacek et al., 2010).

- Low (≤5°C/45°F) and high (˃15°C/59°F)ambient temperatures, wind, and rain were associated with increased dead-on-arrival rates (Nijdam et al., 2004; Chauvin et al., 2011).

- Birds that were transported at 34°C/93°Flost more weight compared to birds transported at 30°C/85°F or 25°C/77°F(Petracci et al., 2001).

- The summer (June, July, August) and winter (December, January, February) have the highest dead-on-arrival rates (Vecerek et al., 2006).

- The negative effects of heat stress are exacerbated by lack of water access.

Journey duration

Prolonged transportation may result in reduced welfare outcomes:

- Broilers that were transported for 3 hours lost more body weight compared to broilers transported for 1 and 2 hours (Arif et al., 2022).

- Dead-on-arrival rates in broilers were higher for journeys lasting >4 hours compared to journeys lasting <4 hours(Warriss et al., 1992).

Lairage

Once the birds arrive at the slaughterhouse, they may have to wait on a truck prior to processing, which is called lairage,

Lairage is the location at the plant where the trucks wait prior to processing. Lairage allows birds to recover from transportation stressors and allows the plant to have a buffer of birds present so that the slaughter line is never unintentionally empty.

Lairage times at slaughterhouses usually range from 2 to 4 hours, but may vary depending on logistics of the slaughterhouse (Rodrigues et al., 2017).

The lairage area can be a warehouse, an open building with a roof, or just an area where the trucks are parked. It may contain fans, misting fans, or heaters. Most U.S. slaughter plants have fans to cool the birds when it is hot.

These conditions may risk bird welfare:

- Using white lights in the lairage area is more stressful to broilers compared to using blue lights (Barbosa et al., 2013).

- A prolonged lairage time can increase the risk of birds dying prior to processing (Chauvin et al., 2011; Nijdam et al., 2004).

- Thermal conditions during lairage may cause heat stress (Warris et al., 1999),

- Temperatures above 28°C/82°F were associated with a higher dead-on-arrival rates compared to temperatures below24°C/75°F (Vieira et al., 2011).

Conclusion

The pre-slaughter phase for broiler chickens is a period that contains many stressors and risks for animal welfare.

- Feed and water withdrawal: This can lead to hunger, weight loss, thirst, dehydration, and distress.

- Catching: This can lead to fractures, bruising, distress, fear, and mortality. Mechanical catching, upright catching, or effective training of catching staff could minimize some of these issues, but they may need incentive.

- Transportation and lairage: This can lead to thermal stress, distress, dehydration, weight loss, and mortality. Thermal stress poses a significant risk to animal welfare. Although weather and season are beyond our control, climatic conditions could be managed by active ventilation, heating, or even climate-controlled trucks.

Understanding the factors that can lead to negative welfare outcomes is important to make improvements in broiler chicken welfare during the pre-slaughter phase.

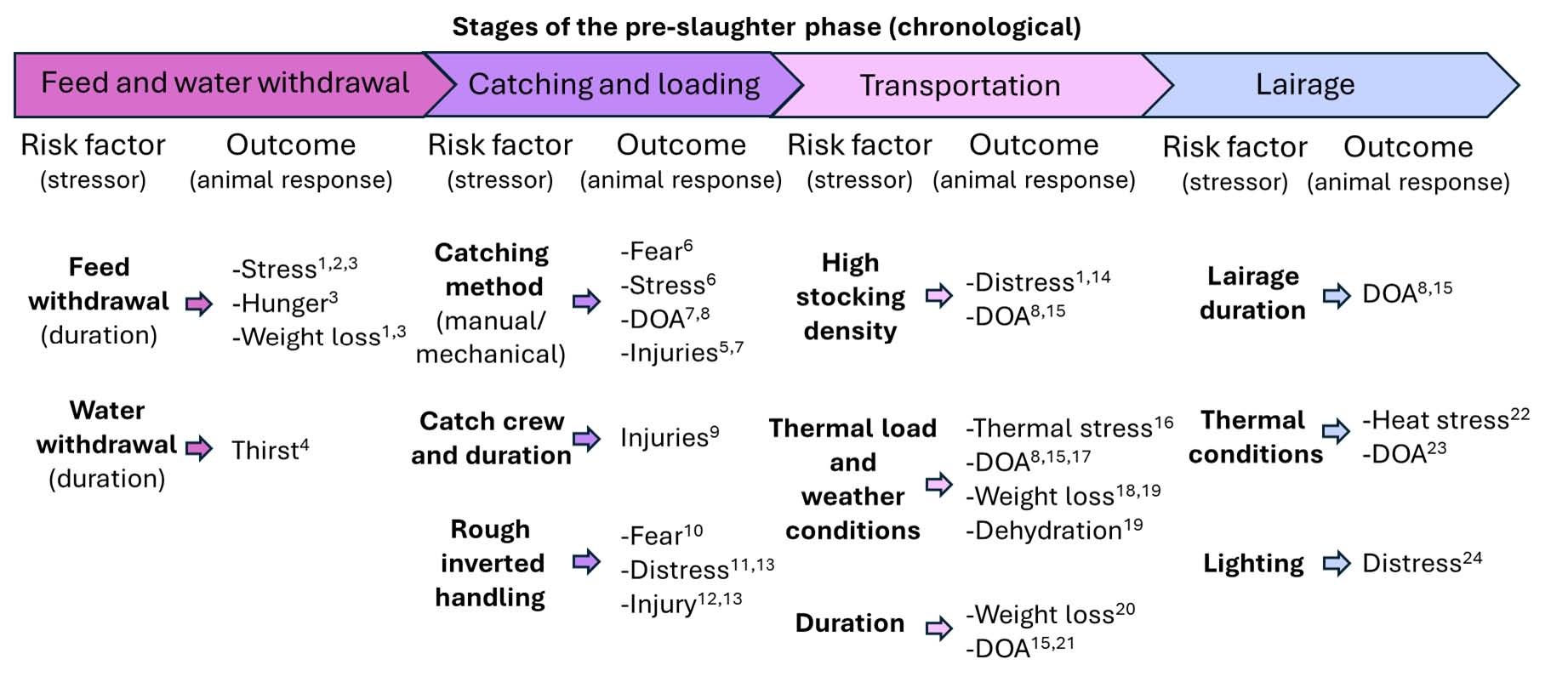

Overview of welfare risks and welfare outcomes per pre-slaughter stage

Summary of risk factors found in scientific literature associated with separate stages within the pre-slaughter phase for broilers. Distress is experienced when an animal has difficulties adapting to the conditions they are exposed to. The animal is unable to adapt to stressors and can experience poor animal welfare. Numbers indicate references. 1. Delezie et al., 2007; 2. Najafi et al., 2016; 3. Nijdam et al., 2005; 4. Vanderhasselt et al., 2013; 5. Smith &Pierdon, 2023; 6. Delezie et al., 2006; 7. Ekstrand, 1988; 8. Chauvin et al., 2011; 9. Jacobs et el., 2017; 10. Jones, 1992; 11. Kannan & Mench,1996; 12. Kittelsen et al., 2018; 13. de Lime et al., 2019; 14. Bedánová et al., 2006; 15. Nijdam et al., 2004; 16. Knezacek et al., 2010; 17.Vecerek et al., 2006; 18. Petracci et al., 2001; 19. Mitchell & Kettlewell, 2009; 20. Arif et al., 2022; 21. Warriss et al., 1992; 22. Warriss et al.,1999; 23. Vieira et al., 2011; 24. Barbosa et al., 2013. Figure adapted from Jacobs & Tuyttens, 2020.

References and further reading

Arif, A., Ibrahim, S. F. M., Abouelezz, K. F. M., & Omar, A. H. M. (2022). Influences of different transport durations on blood biochemical, meat quality, and meat yield of broiler chickens. Archives of Agriculture Sciences Journal, 5(2), 165–179.https://doi.org/10.21608/aasj.2022.147917.1125

Barbosa, C. F., Carvalho, R. H. de, Rossa, A., Soares, A. L., Coró, F. A. G., Shimokomaki, M., & Ida, E. I. (2013). Commercial preslaughter blue light ambience for controlling broiler stress and meat qualities. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 56.

Bedánová, I., Voslárová, E., Vecerek, V., Pistĕková, V., & Chloupek, P. (2006). Effects of reduction in floor space during crating on haematological indices in broilers. Berliner Und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift,119(1–2), 17–21.

Chauvin, C., Hillion, S., Balaine, L., Michel, V., Peraste, J., Petetin, I., Lupo, C., & Le Bouquin, S. (2011). Factors associated with mortality of broilers during transport to slaughterhouse. Animal, 5(2), 287–293. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731110001916

de Lima, V. A., Ceballos, M. C., Gregory, N. G., & Da Costa, M. J. R. P. (2019). Effect of different catching practices during manual upright handling onbroiler welfare and behavior. Poultry Science, 98(10), 4282–4289.https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez284

Delezie, E., Lips, D., Lips, R., & Decuypere, E. (2006). Is the mechanization of catching broilers a welfare improvement? Animal Welfare, 15(2), 141–147. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600030220

Delezie, E., Swennen, Q., Buyse, J., & Decuypere, E. (2007). The Effect of Feed Withdrawal and Crating Density in Transit on Metabolism and Meat Quality of Broilers at Slaughter Weight. Poultry Science, 86(7), 1414–1423. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/86.7.1414

Ekstrand, C. (1998). An Observational cohort Study of the Effects of Catching Method on Carcase Rejection Rates in Broilers. Animal Welfare,7(1), 87–96. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600020285

Global Animal Partnership (2018). G.A.P.’s 5-Step® Animal Welfare Standards for Chickens Raised for Meat. Global Animal Partnership.https://globalanimalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/G.A.P.s-Animal-Welfare-Standards-for-Chickens-Raised-for-Meat-v3.2.pdf

Jacobs, L., Delezie, E., Duchateau, L., Goethals, K., & Tuyttens, F. A. M. (2017). Impact of the separate pre-slaughter stages on broiler chicken welfare. Poultry Science, 96(2), 266–273. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pew361

Jones, R. B. (1992). The nature of handling immediately prior to test affects tonic immobility fear reactions in laying hens and broilers. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 34(3), 247–254.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80119-4

Kannan, G., & Mench, J. A. (1996). Influence of different handling methods and crating periods on plasma corticosterone concentrations in broilers. British Poultry Science, 37(1), 21–31.https://doi.org/10.1080/00071669608417833

Kittelsen, K. E., Granquist, E. G., Aunsmo, A. L., Moe, R. O., & Tolo, E. (2018). An Evaluation of Two Different Broiler Catching Methods. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 8(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080141

Knezacek, T. D., Olkowski, A. A., Kettlewell, P. J., Mitchell, M. A., & Classen, H. L. (2010). Temperature gradients in trailers and changes in broiler rectal and core body temperature during winter transportation in Saskatchewan. Canadian Journal of Animal Science, 90(3), 321–330.https://doi.org/10.4141/CJAS09083

Knierim, U., & Gocke, A. (2003). Effect of Catching Broilers by Hand or Machine on Rates of Injuries and Dead-On-Arrivals. Animal Welfare, 12(1),63–73. doi:10.1017/S0962728600025380

Lacy, M. P., & Czarick, M. (1998). Mechanical harvesting of broilers. Poultry Science, 77(12), 1794–1797. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/77.12.1794

Mitchell, M. A., Kettlewell, P. J., & Maxwell, M. H. (1992). Indicators of Physiological Stress in Broiler Chickens During Road Transportation. Animal Welfare, 1(2), 91–103. Cambridge Core. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600014846

Najafi, P., Zulkifli, I., Soleimani, A. F., & Goh, Y. M. (2016). Acute phase proteins response to feed deprivation in broiler chickens. Poultry Science, 95(4), 760–763. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pew001

National Chicken Council (2022). National Chicken Council Broiler Welfare Guidelines and Audit Checklist. National Chicken Council.https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/wpcontent/uploads/2023/01/NCC-Broiler-Welfare-Guidelines_Final_Dec2022-1.pdf

Nijdam, E., Arens, P., Lambooij, E., Decuypere, E., & Stegeman, J. A. (2004). Factors influencing bruises and mortality of broilers during catching, transport, and lairage. Poultry Science, 83(9), 1610–1615.https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/83.9.1610

Nijdam, E., Delezie, E., Lambooij, E., Nabuurs, M. J. A., Decuypere, E., & Stegeman, J. A. (2005). Feed withdrawal of broilers before transport changes plasma hormone and metabolite concentrations. Poultry Science, 84(7), 1146–1152.https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/84.7.1146

Nijdam, E., Zailan, A. R., van Eck, J. H., Decuypere, E., & Stegeman, J. A. (2006). Pathological features in dead on arrival broilers with special reference to heart disorders. Poultry Science, 85(7), 1303–1308. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/85.7.1303

Petracci, M., Fletcher, D. L., & Northcutt, J. K. (2001). The Effect of Holding Temperature on Live Shrink, Processing Yield, and Breast Meat Quality of Broiler Chickens. Poultry Science, 80(5), 670–675.https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/80.5.670

Rodrigues, D. R., Café, M. B., Jardim, R. M., Oliveira, E., Trentin, T. C.,Martins, D. B., & Minafra, C. S. (2017). Metabolism of broilers subjected to different lairage times at the abattoir and its relationship with broiler meat quality. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, 69.

Smith, K. C., & Pierdon, M. K. (2023). Impact of mechanical vs. Manual catching on stress, fear, and carcass quality in slower growing broilers. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science : JAAWS, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2023.2254226

Vanderhasselt, R. F., Buijs, S., Sprenger, M., Goethals, K., Willemsen,H., Duchateau, L., & Tuyttens, F. A. M. (2013). Dehydration indicators for broiler chickens at slaughter. Poultry Science, 92(3), 612–619.https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2012-02715

Vecerek, V., Grbalova, S., Voslarova, E., Janackova, B., & Malena, M.(2006). Effects of Travel Distance and the Season of the Year onDeath Rates of Broilers Transported to Poultry Processing Plants. Poultry Science, 85(11), 1881–1884.https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/85.11.1881

Vieira, F. M. C., Silva, I. J. O. da, Barbosa Filho, J. A. D., Vieira, A. M. C., Rodrigues-Sarnighausen, V. C., & Garcia, D. de B. (2011). Thermal stress related with mortality rates on broilers’ preslaughter operations: A lairage time effect study. Ciência Rural, 41.

Wabeck, C. J. (1972). Feed and Water Withdrawal Time Relationship to Processing Yield and Potential Fecal Contamination of Broilers1. Poultry Science, 51(4), 1119–1121. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0511119

Warriss, P. D., Bevis, E. A., Brown, S. N., & Edwards, J. E. (1992). Longer journeys to processing plants are associated with higher mortality in broiler chickens. British Poultry Science, 33(1), 201–206.https://doi.org/10.1080/00071669208417458

Warriss, P. D., Knowles, T. G., Brown, S. N., Edwards, J. E., Kettlewell,P. J., Mitchell, M. A., & Baxter, C. A. (1999). Effects of lairage time on body temperature and glycogen reserves of broiler chickens heldin transport modules. Veterinary Record, 145(8), 218–222.https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.145.8.218

Wolff, I., Klein, S., Rauch, E., Erhard, M., Mönch, J., Härtle, S., Schmidt, P., & Louton, H. (2019). Harvesting-induced stress in broilers: Comparison of a manual and a mechanical harvesting method under field conditions. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 221, 104877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2019.104877

To view all issues of Poultry Press, click here.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.