Anyone in live production knows that post-mortem examinations are essential for maintaining a comprehensive, targeted flock-health program.

Anyone in live production knows that post-mortem examinations are essential for maintaining a comprehensive, targeted flock-health program.

Not only do they provide insights into what’s happening within the bird, but these exams also can discover health issues that didn’t present outward signs.

But when it comes to managing viral diseases, is it enough to look at the bursa? Although the bursa is the go-to organ to check during post-mortem exams, it provides only a partial picture.

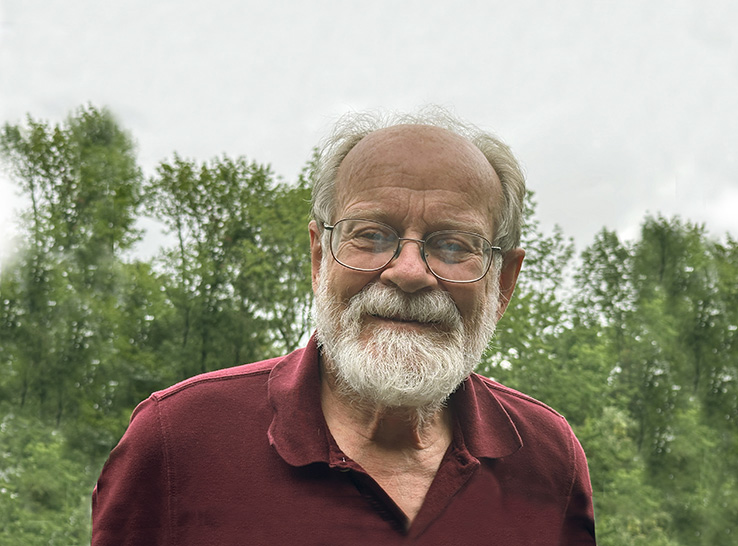

“Always look at the thymus,” emphasizes Karel “Ton” Schat, DVM, PhD, professor emeritus of avian virology and immunology, Cornell University.

“It is a key immunological organ. If you don’t look at the thymus, you miss 50-plus percent of the immune system, potentially leading to an incomplete or misdiagnosis.”

Schat, who delivered a keynote lecture at the 2024 Western Poultry Disease Conference — “The Thymus: A Key Immunological Organ but Often Ignored in the Diagnosis on Avian Diseases” — is on a mission to get avian veterinarians to include the thymus in their standard post-mortem exams.

Avian immune system

The development of the avian immune system depends on the bursa of Fabricius, the thymus and bone marrow functioning together as a complex system, Schat notes. These three organs are susceptible to infections that influence the bird’s immune response. The bursa is the source of B lymphocytes, while the thymus produces T lymphocytes, which are critical for virus immunity.

The bursa gained post-mortem attention in the late 1950s when bursal disease proliferated. “People got the idea that the bursa was important, so everyone started measuring it,” Schat says. “There are instruments that you can use to see how many bursa lobes are normal size or too small. People rapidly learned how to do that.”

The same could apply to the thymus and requires just a few extra steps, he notes. “Open the skin from the breastbone up to the head, fold the skin back, and the thymus is found on both sides of the neck. There are 12 to 14 lobes total or six to seven on each side. It’s a densely packed cortex of cells.”

If the thymus looks “normal,” then the immune response is solid. However, if the thymus has atrophied, it’s time to dig deeper.

“It’s important to know if it’s Marek’s disease (MD), chicken anemia virus (CAV) or something else to determine how we can better protect our chickens,” Schat says.

The long reach of immunosuppression

The bursa and thymus are key organs to determine immunosuppression, Schat notes, and each provides different insights. For example, both Marek’s Disease Virus (MDV) and CAV replicate in the thymus, making it the ideal post-mortem site to identify those viruses.

“Otherwise, you may end up with an incomplete diagnosis,” he says. The thymus also is one of the replication sites for newly discovered cycloviruses and gyroviruses.

It is becoming increasingly clear that MDV, a herpes virus, and CAV, a gyrovirus, can impact the outcome of numerous other infections. Research shows that if a flock is suboptimally protected against MDV and/or CAV then co-infections such as infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), or Infectious Laryngotracheitis virus (ILTV) will linger because both MDV & CAV are capable of disrupting the immune response.

“It is an important message to the industry: CAV is not only a disease of young chickens; it is poorly understood and can cause immunosuppression at any time,” Schat says. “The virus will replicate once maternal antibodies are gone. But you don’t see it because birds don’t become anemic. Also, the immunosuppressive effects of MDV and its effect on opportunistic microorganisms is not well defined, misleading the industry to believe they are dealing with a primary disease when it is “technically” presenting as a secondary disease.”

Both MDV and CAV eventually go latent, but any stress can cause them to replicate, as can estrogen. “If you look at pullets, 17 to 18 weeks of age, they start to produce estrogen, and they can break with CAV when the antibody level is too low,” he notes.

Stress also is a major immunosuppressant and can reactivate CAV, latent MDV and others, causing a cascade of clinical health issues.

Vaccination considerations

Although vaccinations control many avian diseases today, research shows that dual pathogens can disrupt the bird’s immune system and reduce the vaccine response.

Of course, many factors can cause a vaccine to fail, but suboptimal, incorrect application and immunosuppression are the leading factors.

“During the investigation process, you need to be aware of signs that can indicate immune health issues. Is the operation suffering from diseases that are routinely considered as secondary? In the post-mortem exam, you need to look for any lesions of immunosuppression that may negatively impact the antibody titers,” Schat says. “If the thymus is shot, you don’t have T-helper cells, and if a vaccine is based on antibody titers but those T-helper cells aren’t there, the vaccine will fail.”

The current approach in the US is to vaccinate breeder pullets for CAV around 8 to 10 weeks of age to increase maternal antibodies in the progeny, preventing clinical disease. Vaccinating layer pullets may not be needed, although it may help prevent late CAV breaks impacting other secondary diseases as well as MD. Addressing the immunosuppressive effects of MDV and CAV also requires attentive management and reducing stress for the birds, Schat says.

The full impact of MDV, CAV and other gyroviruses on the immune competency of birds and the resulting secondary effects on other diseases needs more research, he contends. But the place to start today is to include the thymus in the post-mortem exam and get a feel for what a normal thymus looks like within the flock. To really understand what is going on, the next step is to send samples in for histopathology and a PCR test, which most laboratories can run.

“Here is the bottom line: If you have a disease that you consider secondary or that you expect to be controlled by vaccination, but it’s not, think immunosuppression,” he says. “You must look at all areas and different potential causes. Is it due to a primary viral infection such as IBDV, MDV and/or CAV? Was there a management error leading to environmental stress? Is it another contributing factor such as a shift in bird genetics?”

Those are all questions to ask during a post-mortem exam.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.