By Stephanie Kulbacki, University of Georgia

Lameness in poultry, characterized by impaired mobility or abnormal gait, is a major concern in fast-growing birds such as broilers and turkeys. Intensive genetic selection for rapid body weight gain and increased breast muscle mass can result in disproportionate growth between the muscular and skeletal systems, predisposing birds to locomotor problems.1

Environmental factors such as poor litter quality and high litter moisture can further aggravate lameness. To identify gait abnormalities and classify lameness, poultry producers and researchers use gait‑scoring protocols and other assessment tools. These approaches support early detection of lameness, inform genetic selection for improved leg strength and fracture resistance, and guide management interventions aimed at reducing the prevalence of lameness. This article reviews common causes of lameness in poultry and summarizes available assessment tools.

Consequences of lameness

Lameness can cause pain and reduced mobility, often limiting birds’ ability to perform natural behaviors, resulting in poor performance and higher culling rates. Affected birds are also more vulnerable to aggression from flock mates. Beyond welfare implications, lameness with skeletal abnormalities can compromise product quality.2

Common causes of gait abnormalities and lameness

Genetic factors, environmental conditions, and their interactions underlie gait abnormalities and lameness in poultry; key causes are summarized below.2

Developmental abnormalities

Valgus–varus abnormality

These deformities are deviations in the tibia that result in varus abnormalities cause the tibia to slant toward the midline, resulting in a “bow-legged” phenotype. Valgus is the opposite with the bone slanting away from the midline, resulting in a “knocked knee” phenotype. These conditions cause the gastrocnemius tendon to flatten and then begin to cover either the lateral or medial condyle of the tibia, which can also make the hock appear thicker.3,4

Tibial dyschondroplasia

Tibial dyschondroplasia is an abnormality, commonly observed in the growth plate of long bones, where cartilage cells that make up the growth plate fail to ossify completely. Studies have found that gait issues due to tibial dyschondroplasia increases as birds age with up to 71% of turkeys displaying signs by 13 weeks of age.5,6

Pathogenic abnormalities

Avian reoviruses

Birds infected with reovirus often develop inflammation of the tendons and synovial joints. When combined with higher body weight, this inflammation can lead to tendon rupture and severe lameness. As the birds get older, reduced tensile strength and elasticity of leg tendons further exacerbate mobility issues.7,8

Bacterial chondronecrosis osteomy elitis (BCO)

BCO is characterized by inflammation of bone and death of cartilage cells, primarily due to bacterial infection. It can occur when rapid increases in body weight cause intense strain on vulnerable plates and cartilage in the bone, ultimately creating clefts or micro-fractures within the growth plates resulting in a breeding ground for bacteria.9,10

Femoral head necrosis

Femoral head necrosis is a common causes of lameness which is observed in severe cases of BCO. It develops when small cracks form in the rapidly growing femoral head and bacteria infects these cracks, causing the death of bone tissue.11

Footpad dermatitis

Footpad dermatitis is when the skin on a bird’s footpad becomes damaged and inflamed, and usually demonstrates thickened scales, black lesions or ulcers in the area. Researchers have analyzed footpads at a cellular level and found issues with the thickening of skin, as well as an increases in epithelial cells.12 For additional information on footpad dermatitis in poultry please check Vol. 9 (2020) of Poultry Press.

Environmental factors such as poor litter quality, high stocking density, inconsistent ventilation, or sudden changes in temperature can exacerbate these conditions.

Subjective gait assessments

A commonly used qualitative gait‑scoring method is the Bristol scale, an ordinal six‑point system in which a score of 0 indicates normal gait and a score of 5 indicates lameness, an inability to take a full step or support its own weight whilst standing.13 Each score is accompanied by specific descriptive gait characteristics. The scale requires careful observation by a trained observer and can be challenging to apply in on‑farm settings.

Abridged Bristol scale for poultry gait assessment (adapted from Kestin et al. [1992] and Kittelsen et al. [2016])

|

Gait score |

Criteria |

|

0 |

No detectable abnormality, fluid locomotion, furled foot when raised |

|

1 |

Slight defect, difficult to define |

|

2 |

Definite and identifiable defect, but it does not hinder the bird in movement |

|

3 |

An obvious gait defect that affects the bird’s ability to maneuver, accelerate and gain speed |

|

4 |

A severe gait defect; the broiler will walk only a couple of steps if driven before sitting down |

| 5 |

Complete lameness, either cannot walk or cannot support weight on the legs |

Another commonly used subjective gait‑scoring method on U.S. poultry farms is the 3‑point scale, which assigns scores from 0 to 2 with increasing severity of lameness.14 A score of 0 indicates normal gait, while a score of 2 reflects marked difficulty in taking steps. Although less detailed than the Bristol scale, this abbreviated system is recommended by organizations such as the National Chicken Council and is better suited for large commercial operations because it is less specific and easy to distinguish between the categories.

Gait scale recommended by the National Chicken Council (adapted from NCC)

|

Gait score |

Criteria |

|

0 |

No impairment. Bird can walk at least 5 feet with a balanced gait |

|

1 |

Obvious impairment. Bird can walk at least 5 feet, but appears awkward, uneven in steps |

|

2 |

Severe impairment. Bird cannot walk 5 feet or there is obvious lameness |

Objective gait assessments

Video recordings have been used to implement computer vision methods to identify individual birds within large groups, not only for gait scoring but also for detecting other behaviors associated with lameness. Exploration into the use of automated or semi‑automated systems to identify specific postures or behaviors that are linked to gait impairments, allowing for human or computer identification of lameness.15-17

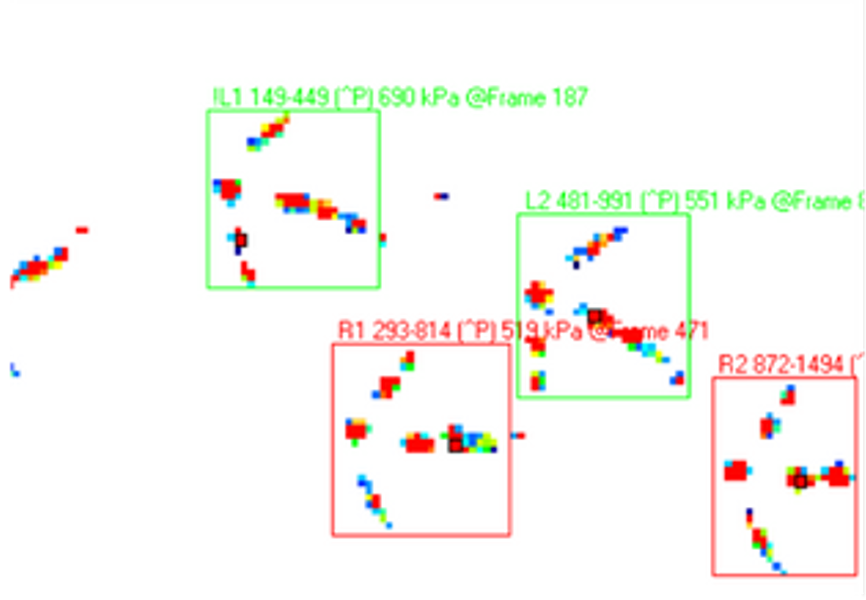

Pressure‑sensitive walkways (PSW) can collect quantifiable parameters from both limbs, including vertical impulse, peak force, kinetic data, step time, and step length. This method provides one of the most objective measures of gait and can be highly accurate when the equipment is properly calibrated. Birds exhibiting signs of lameness often show increased gait time and reduced step length, while asymmetry between the right and left limbs may indicate the onset of lameness. However, these systems can be large and require habituation for use.18

Other tests such as the “latency‑to‑lie” test are not direct gait assessments, but can be used to assess how lameness is affecting a bird. It evaluates how long a bird can remain standing before sitting, with standing duration serving as an indicator of walking ability and overall leg health.19

Summary

Gait is strongly influenced by genetic selection for increased body mass in fast‑growing birds. Gait abnormalities can come from a variety of factors, like nutritional deficiencies, improper litter or bacterial infections. There are various ways to measure these gait abnormalities. The most commonly used systems are subjective scoring systems, which require trained observers but are susceptible to human bias and error. However, newer objective gait‑assessment methods can reduce this bias but often require specialized equipment, incur higher costs, and may demand more space and cleaning compared with subjective scoring approaches.

Resources

- Kapell, D. N. R. G., P. M. Hocking, P. K. Glover, V. D. Kremer, and S. Avendano. 2016. Genetic basis of leg health and its relationship with body weight in purebred turkey lines. Oxford University Press.

- Granquist, E. G., G. Vasdal, I. C. de Jong, and R. O. Moe. 2019. Lameness and its relationship with health and production measures in broiler chickens. The Animal Consortium 13:7. doi doi:10.1017/S1751731119000466

- Dibner, J. J., J. D. Richards, M. L. Kitchell, and M. A. Quiroz. 2007. Metabolic Challenges and Early Bone Development. Poultry Science Association.

- Julian, R. J. 1984. Valgus-Varus Deformity of the Intertarsal Joint in Broiler Chickens. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 25:254-258.

- Knopov, V., R. M. Leach, T. Barak-Shalom, S. Hurwitz, and M. Pines. 1995. Osteopontin gene expression and alkaline phosphatase activity in avian tibial dyschondroplasia. Bone 16:S329-S334.

- Hocking, P. M., S. Wilson, L. Dick, L. N. Dunn, G. W. Robertson, and C. Nixey. 2002. Role of dietary calcium and available phosphorus in the aetiology of tibial dyschondroplasia in growing turkeys. British Poultry Science 43:432-441. doi 10.1080/00071660120103729

- Sharafeldin, T. A., S. K. Mor, A. Z. Bekele, H. Verma, S. L. Noll, S. M. Goyal, and R. E. Porter. 2015. Experimentally induced lameness in turkeys inoculated with a newly emergent turkey reovirus. Veterinary Research.

- Sharafeldin, T. A., Q. Chen, S. K. Mor, S. M. Goyal, and R. E. Porter. 2016. Altered Biomechanical Properties of Gastrocnemius Tendons of Turkeys Infected with Turkey Arthritis Reovirus, Veterinary Medicine International.Huff, G. r., W. E. Huff, N. C. Rath, and J. M. Balog. 2000. Turkey Osteomyelitis Complex. Poultry Science 79:1050-1056.

- Wideman, R. 2016. Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis and lameness in broilers: a review. Poultry Science 95:325-344.

- Wideman, R. F., and I. Pevzner. 2012. Dexamethasone triggers lameness associated with necrosis of the proximal tibial head and proximal femoral head in broilers. Poultry Science 91:2464-2474. doi dx.doi.org/ 10.3382/ps.2012-02386

- Mayne, R. K., P. M. Hocking, and R. W. Else. 2006. Foot pad dermatitis develops at an early age in commercial turkeys. British Poultry Science 47:36-42. doi DOI: 10.1080/00071660500475392

- Kestin, S. C., T. G. Knowles, A. E. Tinch, and N. G. Gregory. 1992. Prevalence of leg weakness in broiler chickens and its relationship with genotype. Vet Rec 131:190-194. doi 10.1136/vr.131.9.190

- Webster, A. B., B. D. Fairchild, T. S. Cummings, and P. A. Stayer. 2008. Validation of a Three-Point Gait-Scoring System for Field Assessment of Walking Ability of Commercial Broilers. Poultry Science 17:529-539. doi 10.3382/japr.2008-00013

- Weeks, C. A., T. D. Danbury, H. C. Davies, P. Hunt, and S. C. Kestiin. 2000. The behaviour of broiler chickens and its modification by lameness. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 67:111-125. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00102-1

- Dong, Y., G. Fraley, J. Siegford, F. Zhu, and M. Erasmus. 2023. Environmental and genetic strategies for improving leg health and walking ability of commercial turkeys. PLoS One:20.

- Van Hertem, T., T. Norton, D. Berckmans, and E. Vranken. 2018. Predicting broiler gait scores from activity monitoring and flock data. Biosystems Engineering 173:93-102. doi 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2018.07.002

- Kremer, J. A., C. I. Robison, and D. M. Karcher. 2018. Growth dependent changes in pressure sensing walkway data for turkeys. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 9.

- Kaitlin Wurtz, Sigga Rasmussen, Anja Riber, Research Note: Testing the validity of latency-to-lie tests without water for objective on-farm assessment of walking ability of broiler chickens, Poultry Science, Volume 104, Issue 1, 2025, 104577, ISSN 0032-5791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104577.

To view all issues of Poultry Press, click here.

Editor’s note: Content on Modern Poultry’s Industry Insights pages is provided and/or commissioned by our sponsors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and compliance.

Feature photo credit: W. Dier